Inside the problems plaguing the prison estate

13 min read

Unable to innovate or even buy basic materials, and struggling to keep staff while operating antiquated systems, prison governors are trapped in a failing system, reports Tali Fraser

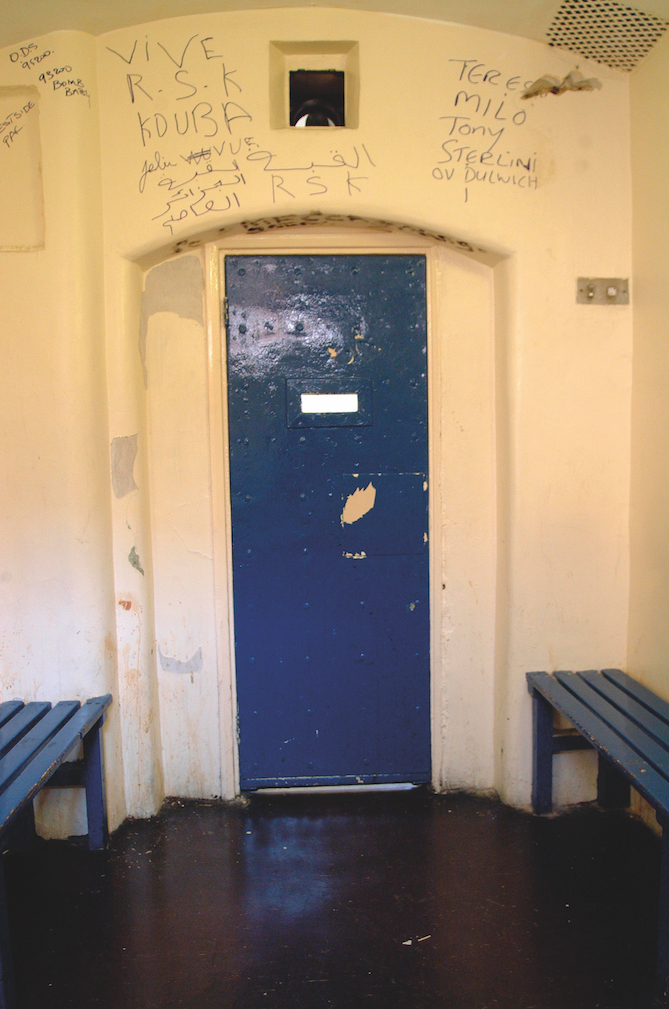

What can one visit to a single jail reveal about the state of Britain’s entire prison estate? For MPs on the Justice Committee who toured HM Prison Brixton earlier this year, the answer proved to be eye-opening.

With a near-maximum 740 inmates, Brixton may be the country’s most overcrowded category C prison, but the challenges the MPs identified are typical of the whole system: the huge difficulty of keeping experienced staff, antiquated record-keeping often reliant on paper documents, and an overly bureaucratic and underfunded procurement system.

“I’ve been to prisons before so I kind of knew what to expect,” says Linsey Farnsworth, the new Labour MP for Amber Valley and the party’s national mission champion for safer streets, having worked as a Crown prosecutor for 21 years and a defence lawyer for a year before that.

But even Farnsworth was surprised by some of the issues: she was struck that the jail wasn’t struggling to recruit staff – it was struggling to retain them. Farnsworth says it serves as “a good indicator” of the demanding role for staff on the prison estate: “They had high levels of new staff as a consequence of not retaining staff, and so on the operational side of things they didn’t have a lot of experience.”

“There were only two or three people that had worked at HMP Brixton for a significant period of time,” Farnsworth continues. One, she adds, had worked at Brixton for around 30 years and “he said that was kind of a job for life in his view, whereas clearly people aren’t seeing it that way now”.

The experienced member of staff at HMP Brixton told MPs how, when they started work, staff would receive induction training for two to three months, whereas now it is only weeks before being placed on operational wings of the prison: “I suppose the reality of that situation, compared to maybe what they were expecting, might be linked to the retention issues.”

Prison officers are given basic training of between six and nine weeks before starting in their assigned prison. There is no mandated additional training in mental health, nor training on becoming a manager, says Tom Wheatley of the Prison Governors’ Association (PGA). Prisons are losing officers even to jobs in warehouses and distribution centres.

“The amount of training should be going up. I know that HMPPS [His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service] has plans to increase the amount and length of the training period for prison officers,” Wheatley tells The House. “They’re looking at making the whole of the first year a part of the training process.” This, he says, would be a “far more integrated approach”.

Brixton’s governor, Mia Wheeler, tells a similar story of retention issues, particularly for prison officers in their first two years of work. For the past year and a half, she reports that they have “shut the prison down twice a month to allow for complete staff upskilling, wellbeing and training development”.

The prison service is even turning to recruitment of overseas prison officers – including sponsoring skilled worker visas following a change in visa rules in October 2023 – to deal with staffing shortages, says Mark Fairhurst, chair of the Prison Officers’ Association (POA), the trade union representing prison officers.

Foreign recruits are arriving to work in jails across the country, despite some having little spoken English, the union leader says: “We have reports, and this is confirmed by prison governors, that some overseas recruits struggle to, or simply cannot, speak English.”

Foreign recruits are arriving to work in jails across the country, despite some having little spoken English, the union leader says: “We have reports, and this is confirmed by prison governors, that some overseas recruits struggle to, or simply cannot, speak English.”

Prison governors do not interview for their prison officers. Instead, officers are recruited under a centralised system without in-person, face-to-face interviews, often using Zoom or Microsoft Teams and online assessments instead. It is a practice, Fairhurst says, that is “simply not fit for purpose”.

Overseas recruitment for prison officer roles has taken place since 2023, he adds, with the majority coming from Nigeria.

“The scale of the levels of people from African, particularly Nigerian, origin, who are applying for jobs in the prison service, at the moment they are in the majority by a significant margin,” the PGA’s Wheatley says, clarifying that for several months last year the majority of applications for prison officer roles came primarily from Nigerian nationals.

These individuals are often already living in Britain, he adds, but may have limited rights to work. A change in April 2024 to working visa rules has driven “a sudden increase” among some groups, he says. These changes allow foreign nationals to obtain a skilled worker visa if they have a designated skilled worker role paying at least £38,700, or a new entrant visa if they are earning at least £30,960.

HMPPS confirms it has sponsored foreign nationals but could not disclose to The House exactly how many of its 23,273 prison officers were from overseas.

Prison governors are so disempowered that I’ve heard how some are digging into their own pockets to buy paint to do up bits of the prison

A prison service spokesperson says: “In October 2023, changes were made to the skilled worker visa scheme which has allowed the prison service to sponsor visa applications for foreign nationals.

“All staff – regardless of nationality – undergo robust assessments and training before they work in prisons. Our strengthened vetting process roots out those who fall below our high standards.”

Brixton’s governor says the diversity of her staff serves as a positive, with inmates feeling “our staff group was really representative of them”.

Yet Wheatley says it has created “communication problems” in some prisons, and could cause division where there are disproportionate numbers of foreign prison staff in remote rural areas as “you create some other issues that are about changing the environment around the prison, and you also potentially create issues in your workforce”.

Fairhurst claims that “some sort of scam is going on” where overseas recruits are having English speakers perform online assessments for them, although the POA does not have evidence to support this.

“Our salary overseas in deprived countries would be quite attractive, hence the push for overseas recruits,” he tells The House.

“Our salary overseas in deprived countries would be quite attractive, hence the push for overseas recruits,” he tells The House.

“I can see how that might be possible,” the PGA’s Wheatley adds. “Some people are getting through the assessment, it appears, and then struggling significantly once they get into the operational role and they can’t do what we think the assessment tested that they could.”

Expectations fall short of reality for some of the new recruits. Nigerian recruits to HM Prison Lowdham Grange, Nottinghamshire, are said to have discovered that the prison could not offer them accommodation on arrival, so accessed a wooded area opposite and set up an unofficial camp there.

One of the things affecting prisons across the board is procurement, and Farnsworth says, “what [HMP Brixton] were saying about that was very worrying, if I’m honest”.

Neil Shastri-Hurst, former lawyer and new Tory MP, says: “Certainly over the procurement issues, there was an acknowledgement that this was not a working system… There is a massive procurement issue on prison estates.”

It is something Josh Babarinde, the Liberal Democrat justice spokesperson, has raised with the prisons minister Lord Timpson, telling The House: “Prison governors are so disempowered that I’ve heard how some are digging into their own pockets to buy paint to do up bits of the prison.”

The MP wants to see more of what Timpson stores themselves implement: upside-down management.

“It is about empowering those on the ground who are doing the doing by giving them autonomy over key decisions... We’re not seeing upside-down management being delivered within the prison estate,” Babarinde says.

The PGA’s Wheatley says what Babarinde has been told about governors’ struggles is not new: “I’ve heard of governors having to dip into their own pockets for things. It is less about money not being available and more about internal systems being clunky or bureaucratic, usually.

The PGA’s Wheatley says what Babarinde has been told about governors’ struggles is not new: “I’ve heard of governors having to dip into their own pockets for things. It is less about money not being available and more about internal systems being clunky or bureaucratic, usually.

“Actually, finding a way of procuring something like paint through the appropriate systems is so difficult and clunky that it’s probably not worth the hassle if somebody said, ‘I’ll just go and get it’.”

The procurement problem is demonstrated by Brixton’s drug netting. Built in 1819, the prison has low walls with a single wall perimeter backing onto public roads. It makes drug throwovers, according to Farnsworth, “a particular problem for their prison”, and requires security netting.

In a survey by the HM chief inspector of prisons, 42 per cent of Brixton prisoners said it was easy to get illicit drugs and random testing showed a positive rate of 28 per cent.

“There are prisoners in HMP Brixton who didn’t have a drug problem when they came in,” Shastri-Hurst says. “They do now.”

The plastic netting to prevent drug throwovers collapsed in the snow in 2022, and has numerous patches after prisoners found ways to burn holes through the plastic. “What was shocking was that the security netting degrades,” Farnsworth says. Governor Wheeler told MPs that prisoners “can be quite innovative” in getting around the security measure with the use of batteries or throwing burning material to create gaps for drugs to be thrown through.

Brixton’s governor had to apply centrally for the funding to repair it but, while waiting for the application to be approved, a new financial year rolled over. Instead of the application rolling over too, she was told that she would have to redo her application for the money a second time.

The reality of that situation, compared to maybe what they were expecting, might be linked to the retention issues

“It is complete madness,” Shastri-Hurst says. “For the clock to suddenly restart once you hit the end of the financial year, and it doesn’t matter how far through the process you are, not to keep it on file but to have to redo it, is bonkers… It seems to be a massive bureaucratic issue for no good reason.”

The governor says: “Procurement is definitely more challenging than if you were working in a private environment… It can be frustrating if part of the system doesn’t necessarily align at the right time or something isn’t done as I would hope it to be done, because there’s lots of different people involved in how a lot of the procurement processes happen.”

She recognises it proved a problem in this case: “It did take way too long to get the fixes that were needed because of some procurement and finance issues.”

“Paper,” Babarinde says, “is another thing that was really troubling” at HMP Brixton.

Release documents were not held digitally, Shastri-Hurst describes, so during the recent tranche of early releases “prison workers had to go down to inventory, collect documents and process them manually”, and the same goes for prisoners on suicide watch. “It is all done on a paper file.”

MPs were told of one employee at Brixton given only a few hours’ notice by the Ministry of Justice to double-check someone’s record to sign off an early release.

“When we were first told this, no alarm bells were going off because the assumption was, ‘Oh, cool, they just go on the digital services to check’,” Babarinde recalls. “When the employee said, ‘Oh, yeah, so I had to run to this storage space within the prison’ and then they couldn’t find who had the key, so had to ring around to find who had it.’ It just shouldn’t come to that.”

According to the POA, prison estates across England and Wales are still using paper records when monitoring inmates on Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork (ACCT) plans, otherwise known as suicide watch.

According to the POA, prison estates across England and Wales are still using paper records when monitoring inmates on Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork (ACCT) plans, otherwise known as suicide watch.

“Paper documents only. Always has been,” POA’s national chair says. “I’m not aware of any plans to digitise it.”

One former prison governor says that the system is stuck using paper: “It has just been accepted as the way it’s always been.”

They tell The House: “The courts use a different system to prisons who use a different system to police who use a different system to probation – with all transfers of documents manual. There is not just double but quadruple tapping when it comes to the records system.”

Shastri-Hurst adds: “If you’ve got a prisoner who is on suicide watch, that is all done on a paper file… You can see how a piece of paper gets lost, and that continuity and oversight for prisoners and their welfare is completely lost.”

When it comes to suicide watch, a stunned Babarinde says in any other setting it would be digital with “algorithms to help calculate risk and automate alerts to share when people need to be checked in on”.

Brixton’s governor tells The House that paper documents are used to monitor daily live interactions and observations for those on ACCT plans, but she defends the practice: “There is a need for prison officers to have something in front of them directly every day, that they can update regularly, that they can check in on and that they can use that is mobile across various areas across the prison, because they have to follow prisoners around their activities.”

She adds that there is one level of digital record-keeping, although not done regularly, when there is a case review meeting with the ACCT case manager who will document it on the central system, so if somebody is “reviewing the case from a distance or doing some sort of quality assurance” it is available to them.

The POA similarly tells The House: “It would be difficult to digitise it anyway due to the lack of IT equipment on the wings. Expecting staff to log on to a computer four times an hour, if that’s what they have to do to record checks, is impractical.”

But, for example, the coroner investigating the death of Frazer Williams who took his own life while on an ACCT at HM Prison Guys Marsh in Dorset, flagged that “as the ACCT is a paper-based system, a missed case review is not automatically flagged in any way”.

Rosanna Ellul, policy and parliamentary manager for the state-related deaths charity Inquest, says: “Outdated systems for identifying prisoners at risk of harm are clearly unacceptable. However, digitisation of ACCTs or other critical processes in prison will not be enough to address the appallingly high levels of self-harm and self-inflicted death across the estate. Urgent action is needed to ensure all prisoners have access to the care and support they need, and prisons must strengthen the ways in which they learn from deaths in custody.”

Farnsworth adds: “When I was going into prisons years ago as a defence lawyer, I remember it being paper. So it was a bit of a shock to me when we walked in and I saw that documents for prisoners were all still on paper.”

Babarinde warns that the prison estate is “even further behind the fax machine culture” in the NHS, where the Health Secretary has been talking about ramping up digitisation: “It was a shared view among MPs from the committee and the prison staff that the whole manual record situation was ridiculous.”

Farnsworth, one of Labour’s mission champions, adds that she hopes prisons are included in the digitisation rollout across government. Babarinde says: “It needs to be.”

Spending money to make prisons function better is not seen to be a natural vote winner, but looking at the prison estate through the lens of HMP Brixton paints a stark picture. As crime creeps up the political agenda, it is an issue that could, in the long term, both create a safer society and save money.

PoliticsHome Newsletters

Get the inside track on what MPs and Peers are talking about. Sign up to The House's morning email for the latest insight and reaction from Parliamentarians, policy-makers and organisations.