The Earl of Clancarty reviews 'In the Eye of the Storm'

'Carousel' by Davyd Burliuk, 1921 | Image © The Burliuk Foundation

4 min read

Mounted at a time when Russia is doing its best to annihilate Ukrainian cultural identity, this enthralling exhibition has a backstory worthy of a Hollywood action film

The story of how, in 2022, treasures from Kyiv’s National Museum of Art were removed from Ukraine to safety has the makings of a Hollywood action film. Piled into lorries and driven across Ukraine on a Tuesday (since Russia usually bombed on Mondays), they reached the Polish border only to find it closed because a missile had landed nearby. Cue lengthy diplomatic discussions before the lorries were eventually let through.

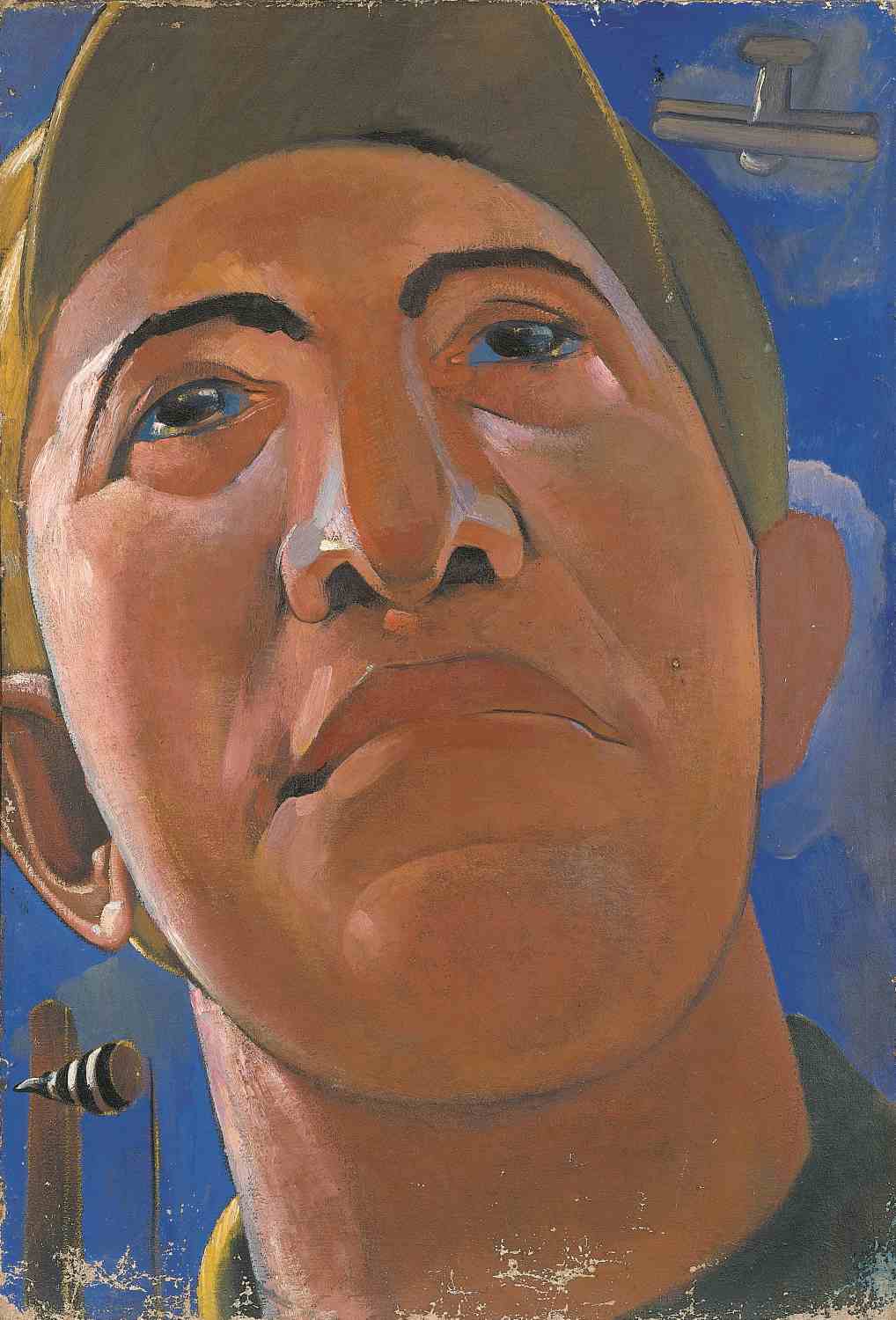

Portrait by Kostiantyn Yeleva, late 1920s | Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine

Portrait by Kostiantyn Yeleva, late 1920s | Image courtesy of the National Art Museum of Ukraine

Much of this art, bolstered by judiciously chosen pieces from other collections, forms the basis of a new show at the Royal Academy, the last stop in a European tour. Inevitably this is a political event as well as an art exhibition, with the curators avowedly challenging Russia’s claim on this art, to reaffirm a Ukrainian artistic identity.

Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out how quickly art history – from our own perspective – can be rewritten in reaction to geopolitical change. The catalogue of the 2014 Kazymyr Malevych Tate exhibition (no mention of Ukraine in the index) tells me in no uncertain terms how much of a Russian artist Malevych was – this despite Ukraine having achieved independence in 1991 (for the second time that century). Malevych, Alexandra Exter and Sonia Delaunay are just some of the internationally famous names amongst many other artists featured in this new exhibition beginning with the onset of modernism (in particular the cubism developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque) and ending with the tragic Stalin purges of the 1930s, when social realism was imposed on art across the USSR. Along the way, the exhibition takes in paintings and sculpture, with one room devoted to theatre design.

It is sobering to realise one is looking at work by artists who were executed

The period is a complicated one. The tumultuous history of Ukraine makes it difficult to disentangle the art from events. Many of the artists moved around, some into permanent exile. Alexander Archipenko emigrated to the USA in the 1920s, with a stop in Paris on the way. Delaunay was born in Odesa but, after childhood, never returned to Ukraine. But some of the most stunning works here are by artists who will not be familiar to us, spending most of their life in Ukraine. These include Oleksandr Bohomazov’s Landscape, Locomotive (1914-15) a riot of colour and rhythm, depicting a train appearing to turn into a landscape (or is it the other way round?). Then there is Vasyl Yermilov’s remarkable Self-Portrait (c 1922) from the post-revolution constructivist period, a painted wood and metal relief whose expression seems to change depending on the angle you look at it. A more socially observant art developed later in the 20s, with artists turning to concerns including poverty and the plight of Jewish communities.

What then of the claim that the work shown here has a primarily Ukrainian identity? There is a convincing argument that Ukrainian artists transformed cubism through introducing colour and movement, often derived from folk art, into a formerly static and monochrome art. One of the last rooms in the exhibition is devoted to the most consciously nationalistic work in the exhibition: the group surrounding Mykhailo Boichuk. It is sobering to realise one is looking in this room at work by artists who were executed, alongside so many others of the intelligentsia across the Soviet empire. It is difficult today to imagine how such a quiet but nevertheless subtle art could provoke such a reaction.

What then of the claim that the work shown here has a primarily Ukrainian identity? There is a convincing argument that Ukrainian artists transformed cubism through introducing colour and movement, often derived from folk art, into a formerly static and monochrome art. One of the last rooms in the exhibition is devoted to the most consciously nationalistic work in the exhibition: the group surrounding Mykhailo Boichuk. It is sobering to realise one is looking in this room at work by artists who were executed, alongside so many others of the intelligentsia across the Soviet empire. It is difficult today to imagine how such a quiet but nevertheless subtle art could provoke such a reaction.

This is an enthralling exhibition, mounted at the same time that Russia is doing its best to annihilate Ukrainian cultural identity. Anyone who takes an interest in the current Ukraine conflict should certainly visit this for a better understanding of the nature of that identity during the past century.

Earl of Clancarty is a Crossbench peer

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s

Curators: Konstantin Akinsha, Katia Denysova, Olena Kashuba-Volvach & Ann Dumas

Venue: Royal Academy, London W1; until 13 October

PoliticsHome Newsletters

Get the inside track on what MPs and Peers are talking about. Sign up to The House's morning email for the latest insight and reaction from Parliamentarians, policy-makers and organisations.