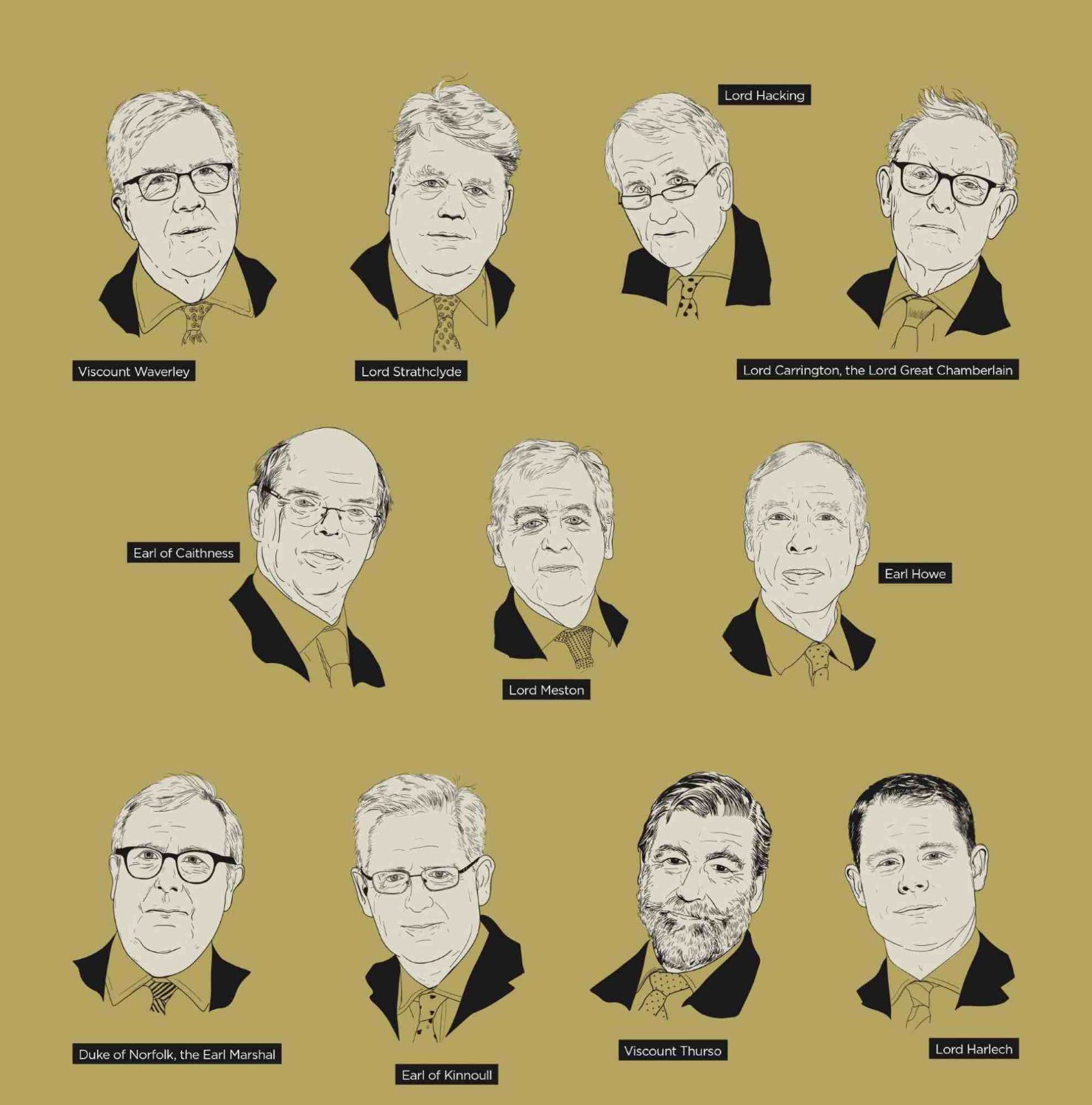

'Parliament is already diminished': The mood of hereditary peers as they head for the exit

8 min read

Tony Blair spared 92 hereditary peers in 1999 because he thought they would soon be swept out in a wider reform to the House of Lords. Daniel Brittain samples the mood of the hereditaries a quarter of a century later

“When you are yesterday’s man, it is time to go gracefully,” says Viscount Waverley, a crossbench peer. “I won’t be speaking from now on.”

The peer, who intends to resign his seat quietly rather than wait for expulsion, has been in the Upper Chamber for 35 years.

The founder of five think tanks had just returned from Uzbekistan, and was about to head off to China and the UAE when he spoke to The House.

“I’m a globalist. My interests are geopolitics, geo-strategy and international trade,” says the peer, whose extensive travels give him a perspective rare among those outside the Foreign Office.

“The doorkeepers, the support staff – we’re all one big happy family,” he says when asked what he’ll miss.

That Waverley is still in the Lords is due to a late compromise in the 1999 House of Lords Act to retain some elected hereditaries while abolishing the sitting rights of all 667 hereditary peers.

The public face of that compromise was Lord Cranborne, the opposition Lords leader. However, his then chief whip, Lord Strathclyde, reveals that the real éminence grise was Alastair Goodlad, his counterpart in the Commons.

Goodlad was close to Robert Cranborne, and Derry Irvine, Lord Irvine of Lairg, Tony Blair’s lord chancellor and champion of a largely elected Lords. After the two Tories told him outright abolition would require the Parliament Act to be pushed through (delaying them a year), Irvine proposed temporarily retaining 50 hereditary peers. They’d be a spur to move on to “stage two”, the largely elected House. Later Cranborne pushed it to 75, and a further manoeuvre increased it by 15, making 90. Finally, adding the Earl Marshal and Lord Great Chamberlain was the icing on the cake.

In November 1998 Irvine, Goodlad, Cranborne, and Murdo Maclean of the government whips office entered No 10 by the back door to meet Tony Blair. “Do we have a deal?” asked Blair. They did.

Events moved fast. Cranborne rang William Hague, the Tory leader, to tell him of the agreement. Key shadow cabinet members were against, however.

Cranborne held a meeting of Conservative peers. Strathclyde describes how Hague, Michael Ancram and Sebastian Coe suddenly swept in. “This is an outrage – you must desist,” he recalls them protesting. “No,” said Cranborne who headed back to his office followed by Hague, Strathclyde and Lord (Peter) Carrington. “I resign,” said Cranborne. “No, you don’t,” said Hague. “You’re fired.” Yet as Cranborne said at the time: “To use a vulgar phrase, I had Hague bang to rights.”

The Lords should be the grit in the shoe of the executive. That won’t work if they’re all appointed

A further deal, again brokered by Cranborne and Irvine, resulted in the by-elections to replace any of the hereditaries when they died or retired. Irvine was happy to agree because, he said, “they’ll never happen”. The Lords would soon be largely elected, he believed. As the Earl of Caithness says, “We thought ‘stage two’ would soon abolish us.” A quarter of a century later, he reflects on what proved to be a much longer escape. “I’m very lucky to still be here. It’s been an amazing time,” he says.

Lord Strathclyde calls the present bill “a shoddy political act”, declaring that the government is not thoughtful or sensitive to the constitution. “Their only thought is, hereditaries bad – they must go,” he states.

Lord Meston, a crossbencher and former judge, queries the Conservatives’ inactivity on reform during 14 years of office. “Why didn’t they do anything? That’s made it hard for them to seriously oppose the present plans,” he argues.

“Cameron said it was a third-term issue,” says Strathclyde, who believes in a largely elected Lords with input from mayors and devolved parliaments. “But the real reason was because he thought he’d never get agreement from his own party.”

His colleague Earl Howe, deputy leader of the Lords until the election, agrees, saying: “There always seemed to be something more important. I did raise it with a very important person, saying the government must come up with a long-lasting plan. We had an opportunity which we missed.”

The Leader of the Lords, Labour’s Baroness Smith of Basildon, recently acknowledged the hard work of most hereditaries and singled out Earl Howe for special praise, with a hint of a life peerage. Earl Howe says: “My ears were turning so red I had to go and watch the rest of the debate on the monitor. I want to see a largely elected House with a far stronger Holac [House of Lords Appointment Commission].”

Rather surprisingly the Earl of Caithness, with 55 years in the House and regarded as very much a traditionalist, agrees. “The Lords should be the grit in the shoe of the executive. That won’t work if they’re all appointed – just look at some of Boris Johnson’s appointments,” he says.

Another peer singled out by Smith is the Earl of Kinnoull, convenor of the crossbench peers and a full-time peer, having given up his outside financial interests. He forms opinions on Lords reform on the basis of research as befits a qualified barrister with an interest in administration.

“Abolishing hereditaries, insisting peers attend at least 10 per cent of sittings and new peers to be subject to an age limit, would reduce membership at the end of the Parliament by about 240,” says the earl. Research by King’s College London showed that conventions between the Houses have frayed. “We’ve been playing ping-pong on more bills, with more balls and longer rallies. Governments are entitled to pass bad law,” he adds.

For Parliament to accept all this, he says prime ministers must accept Holac’s views on the propriety and suitability of prospective new peers.

Would he accept a life peerage? “Maybe, but not if I’m part of the selection process. I couldn’t look my colleagues in the face.”

Image by: Tracy Worrall

Image by: Tracy Worrall

A wholly appointed House is probably the preferred option of most peers. For instance the crossbencher Lord Carrington, and Lord Hacking, a rare Labour hereditary, are united in saying there should be no place for hereditaries but that elections “would not attract top talent and just produce duds; people who couldn’t make it into the Commons”.

Elected in 2018, Carrington (son of the former foreign secretary) is a regular contributor on rural industries, housing and planning. He is though rather more exercised about losing his guaranteed seat as Lord Great Chamberlain, which he inherited on the King’s accession. He sees himself as an activist in this ancient office, increasing the number of parliamentary occasions he attends compared to his predecessor and likes to play an influential role in them. “It will be far harder to do the job if I’m not a regular parliamentarian,” he says.

Lively, and a witty conversationalist, Hacking’s Lords career spreads over 50 years. He’s been a crossbencher and briefly a Conservative, until joining Labour in 1998. “I’m a natural crossbencher, independent in thought, speech and action,” he says, illustrating that by proclaiming: “Labour has become a class party. I’m passionately against VAT on private schools.”

At 83 he was the oldest peer to win a by-election when he returned in 2021 after a 22-year gap. He regards the quality of all hereditaries as something to be proud of and complains too many life peers don’t attend. “However fine we are, we should go,” he says, backing Labour’s policy wholeheartedly. He predicts, though, that – just like under Blair – the next stage of promised Lords reform will never happen.

One peer who has had a unique experience is the Lib Dem Viscount Thurso. He “cheerfully” left the Lords in 1999 for a Commons career from 2001 to 2015 and then returned to the Lords in a 2016 by-election. “It was weird coming back, Groundhog Day, but I’ve liked being back,” he observes.

For 45 years he’s argued for an almost entirely elected House and 15-year terms with a third elected every five years, saying: “Parliament has become weakened compared to the executive. It needs a second chamber respected by the public, media and the Commons. People with experience are good, but people with judgement are best.” He adds somewhat pessimistically: “I’d love to think after 30 years here there’d be reform, but I rather doubt it.” Most peers agree with him. “I’ll miss it, but I always look forward,” he adds.

Lord Meston says he, Hacking and Thurso, are an “oppressed minority” – three peers expelled in 1999 who’ll be expelled again. He waited a record 24 years until returning in the penultimate by-election just 16 months ago; it’s going to be a short stay. “I’ve been working hard since my return, but it’s very disappointing to be expelled again,” he says.

The youngest hereditary, the 38-year-old Lord Harlech, defends the present composition. “The Lords is fit for purpose,” he says. “I’ve treated the role with commitment and service since being elected in 2021. Parliament is already diminished vis-à-vis the executive – this bill takes that a lot further.”

He has support though. A passing former Labour minister and life peer growls: “Leave well alone.”

PoliticsHome Newsletters

Get the inside track on what MPs and Peers are talking about. Sign up to The House's morning email for the latest insight and reaction from Parliamentarians, policy-makers and organisations.