Veterans - A Time to Remember and Reflect

Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward is an 1874 oil painting by British social realism painter Luke Fildes; the man in the red coat on the far right is a soldier.

As crowds gather for the National Service of Remembrance on Sunday 12 November, the nation has a rare opportunity to reflect on its relationship with the Armed Forces. They are a shrinking cohort, from around 4.9million at the end of WW2 to just 142,560 active personnel in 2023. (77,540 Army, 32,180 Royal Air Force, 26,330 Royal Navy, and 6,510 Royal Marines). Dr Hugh Milroy, CEO of Veterans Aid, explores how the veterans of those services are regarded today - and asks if anything has really changed over the years.

In 1945 the number of men and women serving in the UK's Armed Forces peaked at 4,907,000. Then, just as in 1919, demobbed service personnel flooded the streets seeking employment and housing in a world that had changed beyond recognition - much like the post-pandemic landscape that we inhabit now, with active conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East causing ripples of social and economic hardship extending well beyond their immediate borders.

Remembrance Sunday offers a rare opportunity for the nation to reflect on how it regards 21st century veterans and their issues. In many respects they have never enjoyed more privileges; around 2,000 organisations have a vested interest in their welfare, they are singled out in the NHS, enjoy transport privileges, the protection of the AF Covenant and the focus of a national Veterans' Strategy and Action Plan.

But as numbers reduce, the public profile of the Armed Forces - and, as a corollary, that of veterans - is shrinking. To some, they remain a uniquely homogenous and venerated group. Others are less enthusiastic. Gen Z interest in military service is low and dropping - yet when 'soldiers' or 'veterans' fall from grace it is evident that they are held to a higher standard than their civilian counterparts.

So where do they fit into today's hierarchy of needs - and why? Are they really a group with unique problems that can only be resolved by, and in, 'military contexts'?

The fact is that men and women have always returned from combat bearing scars - physical and mental - and the nation has always enjoyed an ambivalent relationship with its military. The nature of warfare may have changed since we fought one another with bows and arrows, but the problems that affect veterans today are as old as time.

Lionising, demonising and separating them out as a discrete species may play well in some theatres, but it won't address the root causes of problems like these:

"We live in two rooms behind a fish shop and there are nine of us. My son is home for two months' leave . .

"I have to keep on stamping on the floor to keep the rats away from the bed where my boy sleeps. We have tried high and low and cannot get a house . .

"I am one of the poor devils that is now paying for his patriotism by having two rooms. I have been looking for a flat since January last and offered my full gratuity to get a place, but all the agents tell me that is not enough. I am told that very large sums are offered . .

These could be quotes from Veterans Aid clients in 2023; in fact they are sourced from Hansard - May 1919

Going back even further, to 1890, Rudyard Kipling wrote The Last of the Light Brigade, a poem that recalled the ephemeral nature of Britain’s relationship with its military personnel. ("There were thirty million English who talked of England's might, There were twenty broken troopers who lacked a bed for the night. They had neither food nor money, they had neither service nor trade; They were only shiftless soldiers, the last of the Light Brigade.")

The context changes, but the issues do not. Veterans' basic needs are food, accommodation, employment and healthcare. The rest is window dressing,

Veterans Aid came into being as a humanitarian response to the poverty and adversity caused by unemployment and homelessness in 1932 - a legacy of WW1. Today, 91 years later, it is dealing with the same problems. However, there are dark clouds on the horizon within the sector.

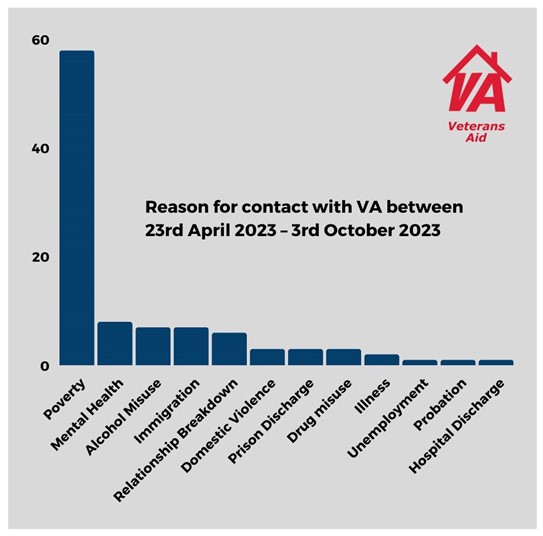

Overall, and despite lots of high-profile effort and initiatives, we are 20% busier than last year. Around 60% of our work relates directly to poverty with many of those seeking help being in work - and 38% have simply been directed to us by other charities. This off-loading is sowing deep seeds of alienation. Charity should flow from compassion but it’s increasingly clear to us in the frontline that it is cumbersome process that is stifling the transformative needs of our clients.

Chronic need deserves an un-fettered humanitarian approach but for many who come to our door their experience within the veterans’ world has been hurtful and they have a certain knowledge that big is not best and rarely satisfies complex need. Surely, we can do better than create veterans who can only be described as perpetual victims?