The Warm Homes Plan: a path to energy efficiency and net-zero goals

Jane Goddard, Deputy Chief Executive Officer

| Building Research Establishment (BRE)

Jane Goddard, Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the Building Research Establishment (BRE), is calling for a focus on retrofitting the least energy-efficient homes to help reduce fuel poverty.

England has come a long way in improving the energy efficiency of its housing stock. In 2004, only 4 per cent of homes had an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of C or better – the standard widely used by the government as a measure of reasonable energy efficiency.1 In the 20 years since, over half – 52 per cent – of households have reached the A to C level of performance, a significant improvement in efficiency.2 The milestone comes as the UK government develops its Warm Homes Plan programme to deliver affordable heating and cut carbon emissions in existing homes. Labour’s election manifesto committed to a doubling of spending on home retrofit, improving five million homes over five years.

Under the newly released data from the government’s English Housing Survey 2023-24, the number of dwellings that are in the bottom energy-efficient EPC categories – in the EPC E, F and G bandings – has fallen to just 9 per cent.2 These E to G banded homes are typically under-insulated. They're more likely to be older, larger and in rural areas.3 They often rely on oil or direct electric heating. Based on 2022 data, the English Housing Survey estimates that energy bills can be twice as high for E, F and G homes as those in the A to C bands.4

As these E to G banded homes make up a small proportion of the housing stock, the question is how much we focus effort on finding, reaching and improving the remaining coldest homes in England. That's a question the government is asking in its newly issued consultation on its Fuel Poverty Strategy and will undoubtedly inform thinking for its Warm Homes Plan retrofit programme. This is because the least efficient homes will need substantial work to achieve a reasonable standard of energy efficiency as a necessity.

BRE's view is that we need to maintain a focus on the coldest, "worst" homes. While they account for less than one in 10 homes, households living in these properties in 2023 constituted one in five (20 per cent) of fuel-poor households.5 These households accounted for an astonishing 55 per cent of the £1.3bn national fuel poverty gap – the total reduction in fuel costs needed for English households to not be in fuel poverty.6 In other words, low-income households in E, F and G homes can face eye-wateringly high bills to keep their families warm.

Unsurprisingly, in the very bottom F and G banded homes, there can be serious health hazards of cardiac and respiratory health caused by cold conditions. BRE's research in 2023 estimated a cost to the NHS of over £500m a year to address cold-related ill-health from homes in these categories.7 Worryingly, despite wider progress on energy efficiency, for low-income households living in these very least-efficient homes, the government’s ‘Review of the Fuel Poverty Strategy: Consultation’ document states that “the number of fuel poor households in Band F and G, has stayed at 5.9%” since 2014.8 This makes the Warm Homes Plan even more mission-critical for government as there is a vital health and energy case for ensuring its success for these homes and households.

So how can the Warm Homes Plan do things differently? Finding routes to unlock investment from the NHS and turning that potential for health sector cost savings into funding for home improvements will be key. Likewise, local authorities need to know where to find the least efficient homes.

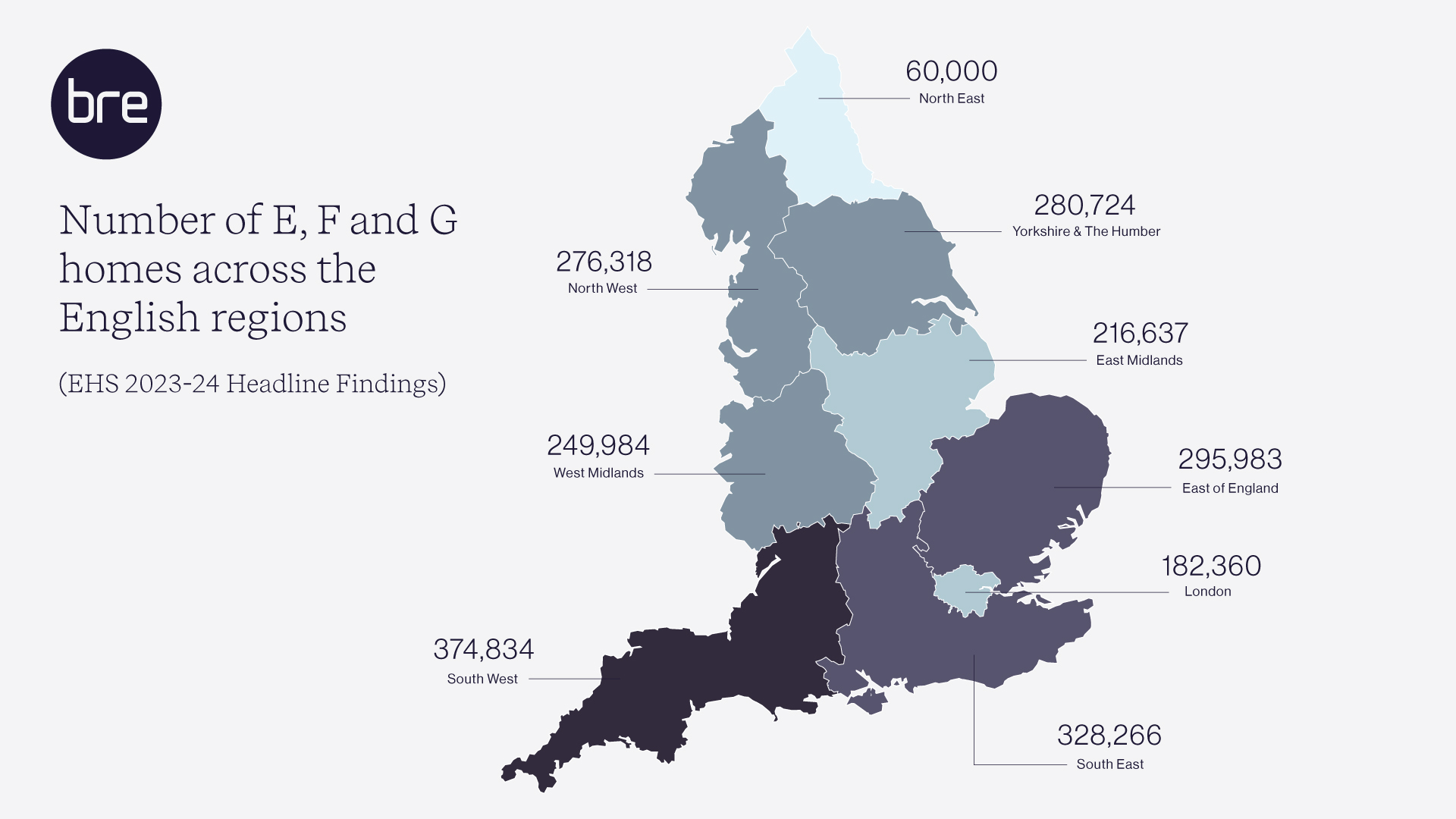

The combined authorities and new strategic authorities will be critical to ensure that the government’s Warm Homes Plan is a success. As shown on the map, there is a significant disparity between the English regions; the South West has 374,834 of the country’s least efficient homes, and the North East has just 60,000. The new strategic authorities alongside existing combined authorities will have a role in delivering the transition to net-zero, and mayors will also control retrofit funding as part of the Integrated Settlements.9 Likewise, mayors will need to prioritise monitoring the coldest homes in their areas, and target support programmes at the owners and occupiers of these properties.

By making targeted, strategic decisions that focus on the coldest homes at a local and regional level, we can make significant strides towards improving energy efficiency, reducing fuel poverty, and cutting carbon emissions across England.

To read BRE’s Warm Homes Plan briefing note in full, please click here.

References

- English Housing Survey Headline Report 2014-15, UK Government

- English Housing Survey Headline Findings 2023-24, UK Government

- Energy Efficiency of Housing in England and Wales, Office for National Statistics

- EHS estimated that in 2022 these homes typically spend £2,662 on energy bills compared to £1,081 homes that are banded C or better. English Housing Survey 2022-23 Energy Report, UK Government

- Review of the Fuel Poverty Strategy: consultation document, UK Government, 2025

- Annual Fuel Poverty Statistics in England, 2024 (2023 data)

- The Cost of Ignoring Poor Housing, BRE, 2023

- Review of the Fuel Poverty Strategy: consultation document, UK Government 2025

- English Devolution White Paper, UK Government, 2024

PoliticsHome Newsletters

Get the inside track on what MPs and Peers are talking about. Sign up to The House's morning email for the latest insight and reaction from Parliamentarians, policy-makers and organisations.