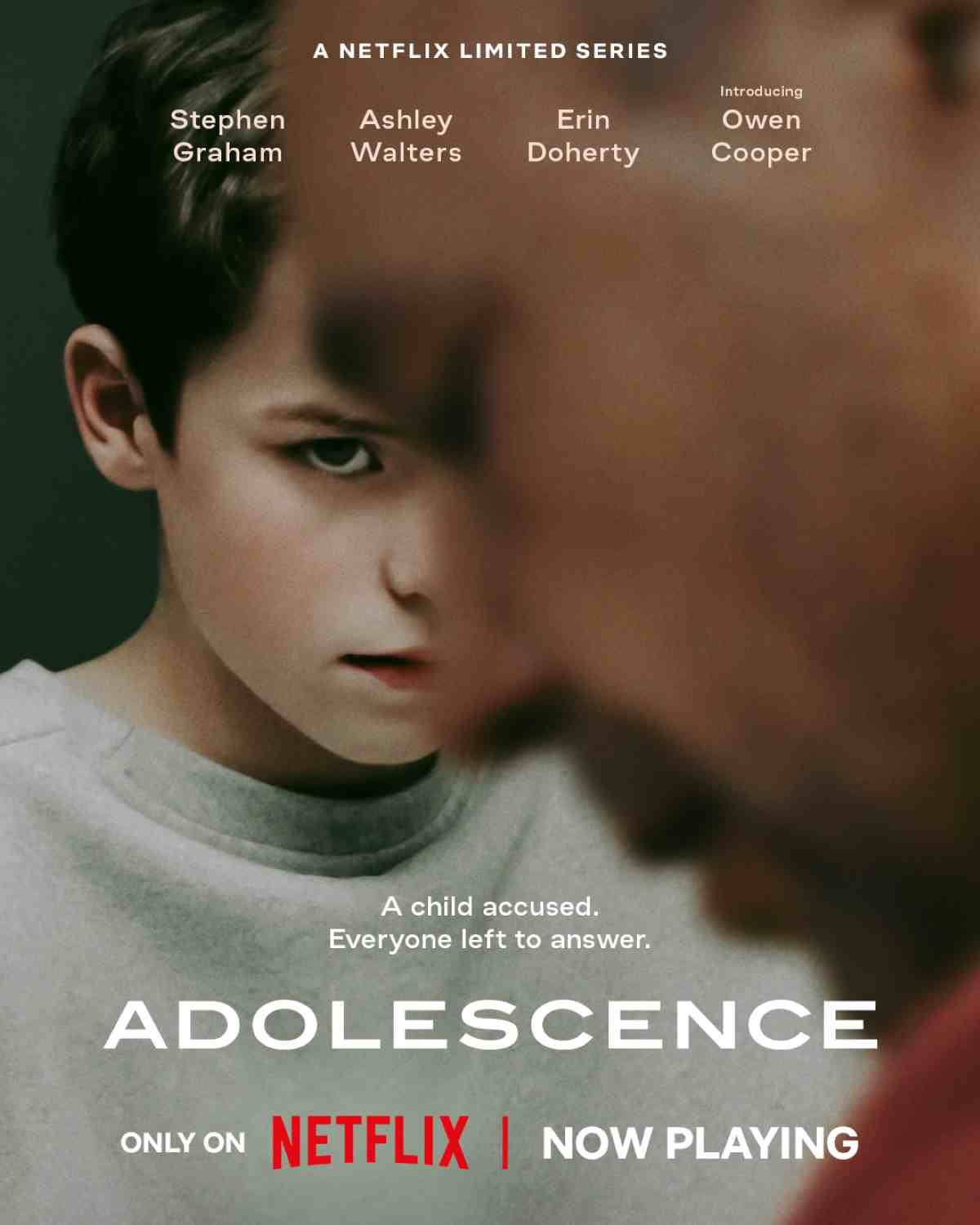

'Brave and compelling television': Ben Bradley reviews 'Adolescence'

Alternating between a scared child and an angry young man: Owen Cooper plays Jamie MIller | Image courtesy of Netflix © 2024

6 min read

In telling the story of 13-year-old Jamie who is arrested on suspicion of murdering a girl, Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham boldly examine masculinity and the role of misogynistic online influencers in this challenging television miniseries

You can’t help but feel sorry for Jamie, the terrified child who is dragged out of his bed in the early hours. Adolescence begins as his family home is raided by police, and he is arrested for murder. He’s so scared that he wets himself. They must have got it wrong, surely? He is just a child.

Starring Stephen Graham (of Snatch and This Is England fame) as Eddie Miller, father of 13-year-old Jamie, the show examines the subject of masculinity – ‘toxic’ or otherwise – and its role in the modern world.

The truth is, Britain is experiencing increasing levels of violence by young boys like Jamie, and horrific stories of young girls knifed to death in the kind of circumstances depicted in Adolescence. It’s brave, I think, of the creators to focus entirely on the impact and circumstances surrounding Jamie and his family. We never see Katie, the murdered girl. We never see how her family are affected by the tragedy and grief. Controversial, maybe. Difficult, certainly. The result is both uncomfortable and fascinating in equal measure.

Stephen Graham as Eddie Miller | Image courtesy of Netflix © 2024

Stephen Graham as Eddie Miller | Image courtesy of Netflix © 2024

Each episode is filmed in a single take. It offers real-time insight into the characters’ thoughts and emotions as they come to terms with what has happened. We soon learn that, despite protesting his innocence and promising his dad that he is telling the truth, Jamie was caught on camera. It seems he is guilty of knifing a young girl to death in a car park near their school.

Viewers will battle with their emotions, watching Jamie shift between a scared child and a very angry young man. You may go from feeling sorry for Eddie, as he tries to cope with the shame and guilt, to pointing fingers at him as he lashes out at the people around him.

This is a pretty normal family. One with working-class roots, and perhaps typical of the average family in my former constituency of Mansfield. Perhaps typical, in truth, of thousands of families in towns all across England. This could happen to anyone – that’s what makes it all so concerning.

It turns out Jamie was bullied online, including by Katie herself. The targeted humiliation was discreet – unrecognisable to older generations who don’t speak the language of emojis and ‘Gen Alpha’. This online bullying followed him to school. As these experiences shaped Jamie, turning him into an angry boy, his parents were entirely unaware. Ask yourself: how could you know?

How do you learn to be a man, without good men around you to learn from?

Over many years in Westminster, I raised concerns about the challenges facing working-class boys – statistically the group in our society most likely to leave school with no qualifications, the least socially mobile, and the most likely to take their own lives. They are the least likely to have a dad at home and typically go to schools with very few (if any) male teachers, so can struggle to find positive male role models. How do you learn to be a man without good men around you to learn from?

Even when dad is at home, it’s not simple. Eddie, despite being a fundamentally good person, is grappling with his own self-worth, upbringing and role in life. “My dad used to beat me black and blue,” he says, “and I promised I would never do that…”

In many working-class communities, stereotypes remain: men are strong; men are providers; men like football and go to the pub. There is a continued acceptance that men and women are different and can have different roles in families and communities.

There is nothing wrong with any of this, but in today’s world – or at least across sections of society – much of it seems frowned upon. Remember the outcry when Theresa May referred to household chores being divided into “boy jobs and girl jobs”?

Erin Doherty as clinical psychologist Briony Ariston and Owen Cooper as Jamie Miller | Image courtesy of Netflix © 2024

Erin Doherty as clinical psychologist Briony Ariston and Owen Cooper as Jamie Miller | Image courtesy of Netflix © 2024

Often, now, masculinity is a dirty word. It’s ‘toxic’. From those quarters, we also hear “men are angry, men are violent”. If you say it enough, the accusation becomes an expectation.

If young boys on the one hand hear from their family and their community that they should be the tough provider yet simultaneously hear from the outside that they should be more feminine and sensitive, no wonder they’re confused. When they don’t seem to fit into the boxes we want to put them in – like not getting on at school – no wonder they look for clear answers.

Increasingly boys and young men find those answers online, drawn to ‘influencers’ spreading misogyny and fuelling anger. Peddling seductive messages, people like Andrew Tate tell these ‘lost boys’ not to be confused, that they are not failures, that they are strong and capable. It’s not difficult to see how angry young men find comfort in that. And when so much of wider society, including politicians, seem to actively avoid talking about issues affecting men and boys, they leave a gaping void that is now filled by social media.

Jamie was a victim, too, in a number of ways. As his parents wrestle with whether they are to blame for their son’s actions, we hear that “he just came home, went up to his room and shut the door” and “he was in his bedroom – we thought he was safe”. The problem is that these days the online world is all-pervasive.

These are scary things to consider, as a parent of two primary school-age boys myself. Our kids have their screens and, like most kids, inevitably they watch things that we don’t see. My wife and I asked ourselves the questions as we watched. What do our kids read and watch online? Do we even know? Will they learn about relationships from us as parents, or from Andrew Tate and the like on social media?

These are scary things to consider, as a parent of two primary school-age boys myself. Our kids have their screens and, like most kids, inevitably they watch things that we don’t see. My wife and I asked ourselves the questions as we watched. What do our kids read and watch online? Do we even know? Will they learn about relationships from us as parents, or from Andrew Tate and the like on social media?

These are important questions for wider society to consider. Are we doing enough to shape our young people, our young men? Or are they increasingly shaped by the dark reaches of the internet, with the ‘real life’ role of parents and other role models taking a back seat? We talk about violence against women and girls but, if we want to tackle it, we have to help our men and boys.

Adolescence raises lots of important issues. It’s full of big questions, rather than answers. It’s a tough watch. And I am very grateful that it was made.

Ben Bradley was Conservative MP for Mansfield 2017-2024

Adolescence

Created by: Jack Thorne & Stephen Graham

Directed by: Philip Barantini

Broadcaster: Netflix