The Other History Makers

1987 general election candidates, left to right: Manzoor Moghal MBE, Zerbanoo Gifford, Nirj Deva and Russell Profitt MBE | Image by Baldo Sciacca

14 min read

The 1987 general election saw the first post-war MPs of colour elected: a moment hailed as watershed moment for diversity in politics. But what happened to those who stood, but weren’t elected? Seun Matiluko tracks some of them down and asks: what happened next? Photography by Baldo Sciacca

“There are some of us in this room tonight who have waited 400 years for this result!”

On 11 June 1987, Paul Boateng, garlanded with white and red flowers, exclaimed these near-immortal words in a jubilant speech following his election as the Labour MP for Brent South. He, alongside Keith Vaz, Bernie Grant and Diane Abbott, had just become the first MPs of colour in Britain’s postcolonial era, with Abbott becoming the first Black woman ever elected to the House of Commons.

Clips from this day are regularly highlighted in the media, particularly during Black History Month. We celebrate them as pioneers who made it possible, in 2023, for there to be 66 ethnic minority MPs and a Prime Minister of South Asian descent.

But what often gets missed is that these four were not the only ethnic minority candidates to run in the 1987 general election.

They were just the only ones to win. There were 29 ethnic minority candidates. Many have now passed away.

We are good at celebrating firsts. The first man on the moon. The first female prime minister. The first Asian Oscar winner. Yet, in our rush to celebrate firsts, we often forget that the people who become the first to do something are rarely the first to have tried doing it. They are just the first to have succeeded.

As one ’87 candidate, Russell Profitt MBE, laments toward the end of our chat: “No-one… has ever asked me to come and talk with them about my experiences, to see what can be learned from it in all these years. And to me, that is regrettable.”

Russell Profitt MBE

Russell Profitt MBE

The Labour candidate for Lewisham East

“Some of us lay the pathways and others tread along it... we should acknowledge the role that both play,” Profitt says, as he joins our Zoom call from South London on a late spring day.

Profitt, who now works as a director of several third-sector organisations, first got interested in politics as a young boy in 1950s British Guiana (now Guyana). “I had grown up in a country where…we had been fighting for independence and I felt that change was imminent and I’d love to be able to play a part in helping to bring that change.”

A member of the Windrush Generation, he arrived in England as a 13-year-old to join his mother, a seamstress, who was then working in a factory. His first memory of the country is a random act of kindness:

“I arrived at the airport without anybody to greet me… somebody, who I suppose must have been part of the airport staff, saw me standing there, pointed me in the right direction, purchased a ticket for me and told me when I got to London I should use the small change he’d given me and ask a policeman which bus I should catch.”

Although Profitt was pushed by his school careers adviser to become a teacher – who told him that more Black teachers “would help schools deal with the emerging population of Black pupils” – his interest in politics did not abate and he soon got close to some school governors who were members of the Labour Party. This got him connected to Andy Hawkins, then leader of Lewisham council, who encouraged Profitt to became a Labour councillor in the 1970s.

“I began [in politics] at a time when there were no Black representatives. I mean, none. You had organisations like CARD (Campaign Against Racism and Discrimination) and the representatives there were church people. I just felt that this was never going to work unless we do something ourselves.”

In 1983 he became a founding member of the Labour Party Black Sections, a group modelled on the American Congressional Black Caucus, to shore up the “Black point of view” in the party as he later told Socialist Action.

Profitt, alongside fellow Black Sections members Abbott, Grant, Vaz and Boateng, fought hard for local and national selection throughout the decade. He eventually secured enough local support to become the Labour candidate for Lewisham East but, because he and others had ensured there was an all-Black shortlist for this seat – “which was contrary to the rules of the Labour Party at the time” – was told he couldn’t run. Other Black Sections members also lost their ribbons due to intra-party conflict, with Sharon Atkin famously deselected following a controversy in which she was said to have called the Labour Party racist.

Nevertheless he ended up being able to run in ’87. “Nearly a month or so before the general election… the party said, ‘Okay, we will endorse you.’ But, by that stage, it had generated quite a lot of controversy… negative headlines and my campaign started off really on the backfoot.”

As the Labour candidate for Lewisham East, Profitt was competing against the incumbent Conservative Colin Moynihan (now Lord Moynihan) and Vivienne Stone of the Social Democratic Party (SDP). The election was tough.

I wasn’t too sure that mentally I could take that ever again

He felt the campaigning was at times underhand, and described a racially-charged atmosphere, with rival activists putting out: “dirty tricks leaflets… I was accused of being anti-police". At one point he sought an injunction over a Conservative leaflet which he said misrepresented his views on immigration. The leaflet claimed he wanted to repeal immigration controls and that he believed “it is the right of anyone to enter the UK without restriction.”

Moynihan – who told The House he would have found it deplorable if Profitt had been exposed to racism because of the campaigning – won by over four thousand votes and received an increase in his vote share. In 1992, he lost his seat to Labour by a little over one thousand votes. Lewisham East has been Labour ever since.

I ask Profitt what it was like to campaign in such a toxic atmosphere. He is a silent for a while before offering, “It was hard.” He looks away from his camera. “I think I went into a fairly deep period of reflection… but, fortunately, I’ve got a family. And I had some good friends. That helped me get out of what was a fairly poor mental state.”

Did he ever think of running again?

“I had… but then I thought about the experiences I had gone through. And the difficulties it had imposed on my family (he had two young daughters). And I wasn’t too sure that mentally I could take that ever again. So I withdrew from active political life.”

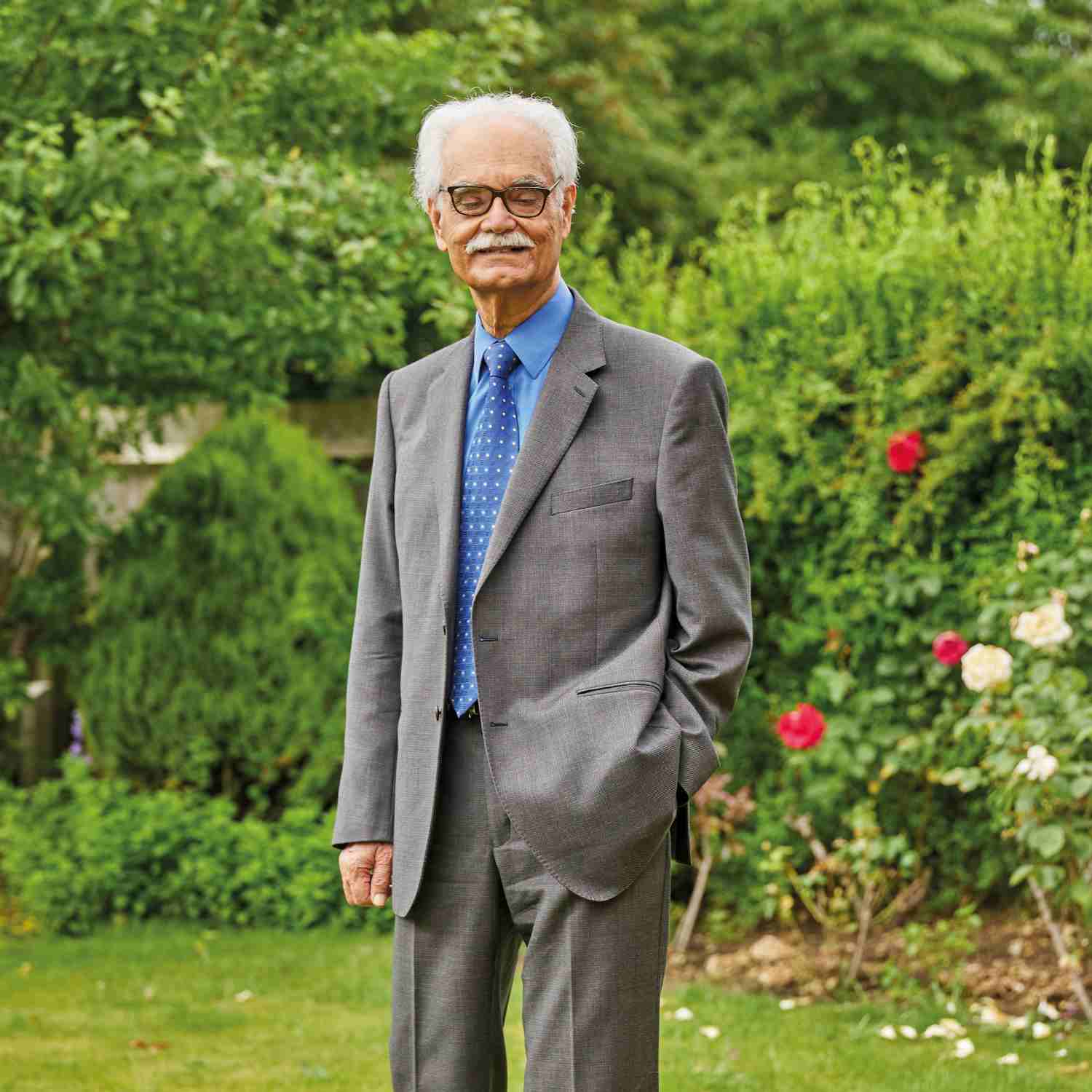

Manzoor Moghal MBE

Manzoor Moghal MBE

The SDP candidate for Bradford West

Profitt was not the only ‘87 candidate to have his campaign negatively impacted by “dirty tricks”.

Manzoor Moghal MBE, who now runs a mortgage broker company, says his campaign as the SDP candidate for Bradford West was brought down by the actions of some Labour supporters: “They sent round thugs, they tore up my leaflets… they threatened Muslim shopkeepers, ‘if you vote for him, we will not give you trading licence’…this is how they browbeat the Muslim voters.”

Moghal was born in British India before moving as an infant to Uganda, upon the outbreak of violence that followed Partition in 1947 (the part of India where Moghal was born later became part of Pakistan).

For a while, in Uganda, Moghal was the deputy mayor of the town of Masaka and part of the political elite. “I took active part in Ugandan politics, in the Asian affairs of Uganda, and I knew the president of Uganda, the kings… the prime ministers.”

They sent round thugs, they tore up my leaflets

However, soon after the rise of Idi Amin, Moghal was forced to leave with his wife and children: “I came to know that my life had been threatened and therefore I had to make all the arrangements hurriedly to flee.” Moghal’s Black friend, who had warned him of the threats to his life, was later “chased down the streets of Masaka…captured… and butchered.”

As a young adult in Leicester, Moghal set up a petrol station with his brother and initially had no plans to re-enter politics. Indeed, a few years after arriving, he made plans to “to leave this country and emigrate to Canada” but, ultimately, decided to stay and make a difference, working with Leicestershire County Council to improve race relations (and winning an MBE in 2002 for these efforts).

In 1981, Moghal turned to national politics following the creation of the SDP by former Labour MPs Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins, David Owen and Bill Rodgers.

In their statement of intent, they said they wanted “an open, classless and more equal society”. This “Limehouse Declaration” shook up the political arena and inspired Moghal to drive all the way up to Bradford to attend their inaugural conference.

He soon got to know some of the higher ups in the party, including Williams, and was eventually selected, to his “great surprise,” as the SDP candidate for Bradford West in 1987.

He left the party just a year later, when they merged with the then Liberal Party to form the Liberal Democrats. Even though nearly every house on the sunny drive to visit Moghal for our interview in Leicestershire, just before the May 2023 local elections, had a sign saying “Liberal Democrats winning here,” Moghal shakes his head in disgust at the memory: “I had no stomach for being a Liberal…for me there was no choice.”

Zerbanoo Gifford

Zerbanoo Gifford

The Liberal candidate for Harrow East

For Zerbanoo Gifford, who was born in newly independent India and was raised by hotelier parents in London, the choice to become a Liberal politician landed on her doorstep.

Two Liberal councillors approached her in 1981 to ask whether they could stick a party poster on the large tree in her garden in Harrow. After they got talking, they eventually asked if she wanted to become a paper candidate in the following year’s local election, i.e. a candidate who would help the party look “more diverse” but had little chance in winning. She thought, “Well…why not?”

It was a hard-fought campaign for the mother of two whose hero, Dadabhai Naoroji, was Britain’s first Indian born MP. In her biography, she describes receiving a call late one night, where a man threatened: “We are not going to let Asians run this country.”

Elaborating, she says, “I was the only young woman (running) in Harrow… only ethnic minority, and of course I got masses of national coverage… I had racist letters. It was awful. And I decided that I wouldn’t give publicity to that because I felt very strongly that if I did people would say, ‘oh, she only won because she called everybody a racist’.”

Even now, Gifford, who is the director of a Forest of Dean based charity that works to develop young leaders, stops me on our phone call to ensure I won’t make it look like she’s “whinging”.

Despite it all, she won in ’82 and, galvanised by this, decided to run as a parliamentary candidate in the newly formed Hertsmere constituency in 1983. Sadly, the racism didn’t subside.

“We had our windows broken. We had my car smashed up… I had a lot of Americans come to campaign because I’d been to America as a guest of the government… they were flabbergasted that I would go campaigning and I would be spat upon. They said there would be riots if that had happened in America.”

They were flabbergasted that I would go campaigning and I would be spat upon. They said there would be riots if that had happened in America

Cecil Parkinson won Hertsmere in ‘83 but Gifford didn’t consider it a true loss as she had “doubled the vote for the Liberals” despite Parkinson being the then chairman of the Conservative Party. So, she decided to run again in ‘87, this time in Harrow East.

She briefly flirted with changing parties – Lord Swraj Paul had advised her, “It doesn’t matter who you join. Why don’t you join one of the major parties because (eventually) you’ll be a minister”– but decided against it. This was despite receiving next to no support from her party during ‘87, as the local Liberals “wanted the leader of the council to be the candidate” and were dismayed that members had selected her instead. The Conservatives ended up winning Harrow East.

In 1992, Gifford ran for the final time, returning to Hertsmere, although by then she had had enough, and describes ‘92 as “not a proper run”: “I was a paper candidate. I really wasn’t interested.”

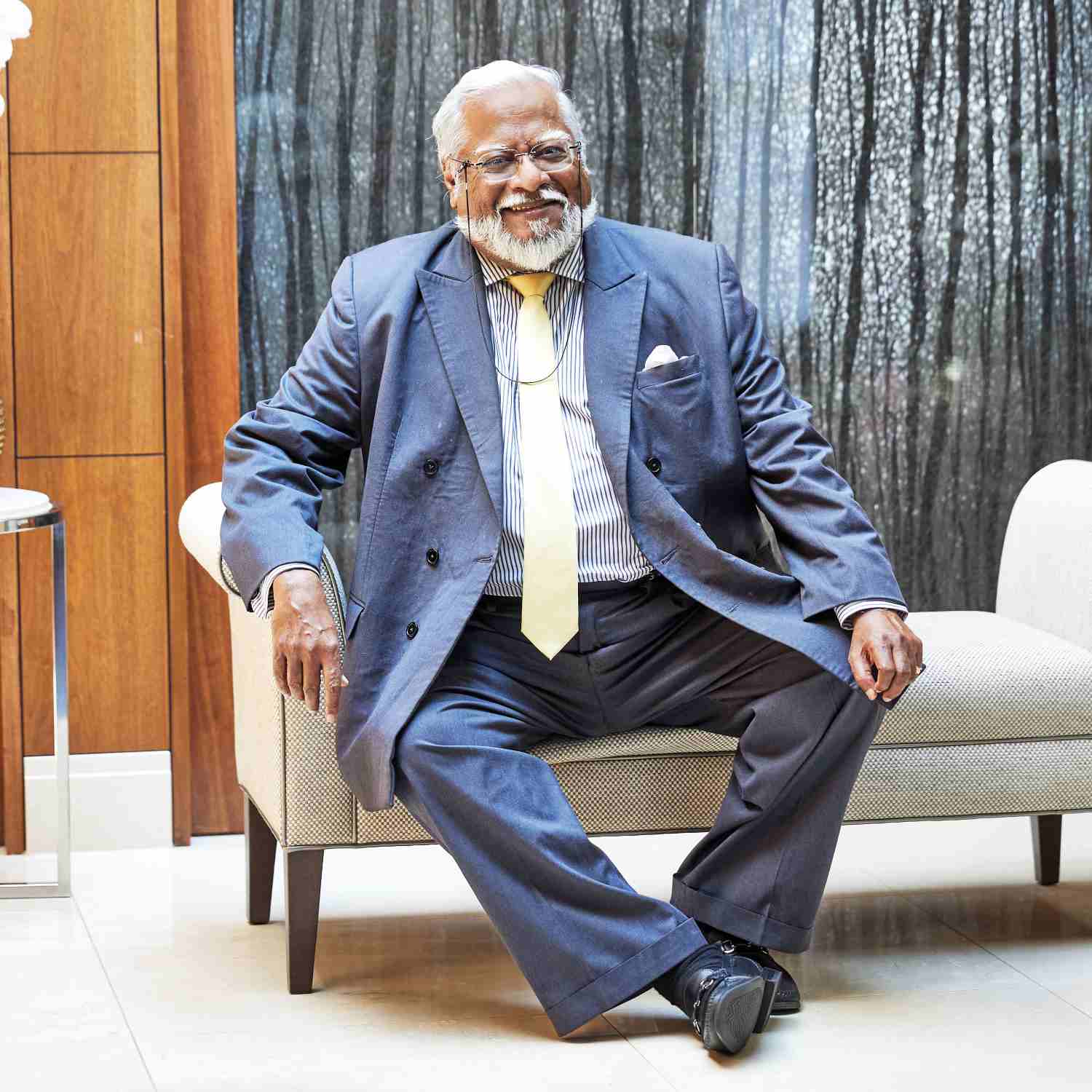

Nirj Deva

Nirj Deva

The Conservative candidate for Hammersmith

While Profitt, Moghal and Gifford did not ultimately become MPs, some of the ethnic minority candidates who almost made history in 1987 later did.

This includes Nirj Deva, who proudly states in his Twitter bio that he was “1st Cons BAME postwar”.

Deva, who tells me I shouldn’t trust anything on his Wikipedia because some Sri Lankan activists keep changing it, comes from a political family. His grandfather was a senator in what was then Ceylon. Yet, the political bug did not bite until Deva travelled from Ceylon to Loughborough to study aeronautical engineering.

While in Loughborough, he was dragged along by a friend to hear a speech by “Willie Whitelaw” – who, when he was Margaret Thatcher’s home secretary, introduced the British Nationality Act so as to “dispose of the lingering notion that Britain is somehow a haven for all those whose countries we once ruled.”

Whitelaw asked the students what they thought of the speech when he was done. Deva told him the speech was “rubbish… [he] spent 40 minutes moaning and groaning about the fact that people want to come and live in Britain”.

Deva’s honesty earned him a job with Whitelaw as a speechwriter.

I get a taste of this honesty when he stops our admittedly scratchy phone call (he’s speaking to me over WhatsApp from Sri Lanka, where he spends large chunks of the year) to ask me point blank “do you want to report on other people doing things or be reported upon doing something?”

If I told you the whole story you wouldn’t believe it

Working for Whitelaw inspired him to think about becoming an MP and so he started making his way up the Conservative ladder – despite a Loughborough friend laughing at him and saying ,“That’s ridiculous. How can you, coming from a foreign country, with no local connections and looking the way you look, become a member of the British Parliament for the Conservatives?”

Deva joined the Bow Group, an influential Conservative think tank, and eventually became its chairman in 1981. This allowed him to connect with several high-profile MPs, including Enoch Powell (with whom he had an “acerbic relationship”), Norman Tebbit (“a very good friend of mine”) and Harvey Proctor, who Deva once debated in his Basildon constituency (“I thought I was going to be lynched”).

After going through around 120 different selection interviews, he was finally selected as the Conservative candidate for Hammersmith in ’87.

Did he enjoy the campaign? “If you want to be insulted in White City, have your car smashed up and told P*ki go home and dogs set on you then yeah, I enjoyed [it]. My canvassers were assaulted. Dear God, if I told you the whole story you wouldn’t believe it.”

Deva lost Hammersmith by just over 2,000 votes. Nevertheless, he felt well supported by some members of the party who did not overly focus on race unlike David Cameron and his “patronising” A-List that came later. “I mentioned to David the other day… I said I had problems with your A-List because once you get on an A-List and get there… you’re not as equal…and he was gracious enough to say, ‘Yes that’s true. But we couldn’t carry on as we were Nirj’.”

Deva finally won a parliamentary seat in 1992, becoming the MP for Brentford and Isleworth even though, traditionally, the MP for that seat had been the president of the Hounslow Conservative Club. “Unfortunately, the Hounslow Conservative Club had a colour bar!” He was an MP until 1997 and then was an MEP from 1999-2019. He now runs an online publication dedicated to Commonwealth affairs.

Back row: Russell Profitt and Nirj Deva; front row: Zerbanoo Gifford with Seun Matiluko

Back row: Russell Profitt and Nirj Deva; front row: Zerbanoo Gifford with Seun Matiluko

The House magazine would like to offer sincere thanks to Conrad London St. James and its staff for hosting the photography shoot used to illustrate this piece