Chinese police stations in the UK have allegedly been shut down. So, what happens now?

Chinese police stations (Credit: Tracy Worrall)

7 min read

Secret Chinese police stations have been found operating in 53 countries across the world. As the government announces that those based in the UK have shut, Sophie Church explores the tactics employed by the Chinese Communist Party to spy on their communities abroad. Illustration by Tracy Worrall

Walking through London one day, Simon Cheng felt a presence behind him. A man in a red t-shirt, who continued to follow him for 15 minutes or so towards his home. When Cheng spotted him, the man jumped on a bus and disappeared.

The next time this happened, when a man in a white car rolled up to the restaurant Cheng was in, Cheng approached him, took out his phone and started filming. The man, clearly nervous, drove away.

Cheng is a pro-democracy activist who previously worked for the British Consulate-General in Hong Kong. At least until he was detained by China’s National Security Police in Shenzhen for 15 days, and then forced to flee to the United Kingdom to claim asylum. Now he is on a wanted list; if he returns to Hong Kong, he will be arrested.

It beggars belief that they were able to operate for some time under the government’s nose at all

While Cheng is only one of six Hong Kong nationals on the list, this type of surveillance allegedly enacted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has become a normal way of life for Hong Kong and Chinese nationals living in the UK. Though Cheng describes the tactics of his sleuths as “clumsy”, Carmen Lau, a Hong Kong district councillor who also fled to the UK, says the CCP’s intimidation can have serious consequences.

“Recently, there is lots of news about… family and friends, who are still staying in Hong Kong or China. They would be asked to have a meeting with some National Security Police,” she says. In these meetings, she says family would be probed for information: Where was their relative? Who were they working with? What were they saying about China?

Simon Cheng at pro-democracy rally in London (Credit: ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo)

Simon Cheng at pro-democracy rally in London (Credit: ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo)

When Safeguard Defenders, a human rights NGO based in Spain, released a report warning that secret Chinese police stations were operating in the UK, Cheng says he was not surprised. The Times has since reported evidence of four police stations: in Croydon, Glasgow, Hendon and Belfast. These stations, which took the guise of takeaways, estate agents or restaurants, were allegedly acting as a front for the CCP to intimidate Chinese citizens in the UK. The Chinese Consulate in Edinburgh claimed they were set up to help Chinese nationals with issues such as renewing their driving license.

This tactic – which Jabez Lam, project leader of the Hackney Chinese Community Centre, recognises as “double-plating” – is well-worn by the CCP, he says. “Double plating means that you have an office, at the front of the office, you have the plaque of the office name and behind, you are doing something else. Those are the tactics developed under the time of the Kuomintang, when the Communist Party was an underground organisation… what they are doing now is just a continuation of the authoritarian regime that oppressed dissidents.”

While just four Chinese police stations have been found in the UK, Lam judges that: “This double plating… has been around for so long that it is into, I dare to say, 90 per cent of Chinese organisations [operating] in the UK.”

As Lam speaks with The House, he pulls up a spreadsheet of Chinese organisations based in the UK that he is investigating for supposed links with the CCP. Some community centres, which had indicated support for Hongkongers coming to the UK on the government’s British National Overseas visa scheme, had silently supported the CCP’s draconian National Security Law, Lam claims. He asks: “Do you think those organisations who signed the statement [are] also suitable to receive money to support Hongkongers to settle?” The CCP has more recently used anti-racism groups in the UK as a cover for its work, claims Lam.

Cheng explains that the CCP has piggy-backed on anti-racist movements in the West to spread its propaganda. “They want to be protected by this… very mainstream narrative in the West and in the UK, and try to be as a disguise to propose [the] CCP narrative agenda,” he says. “Lots of people are not aware of this.”

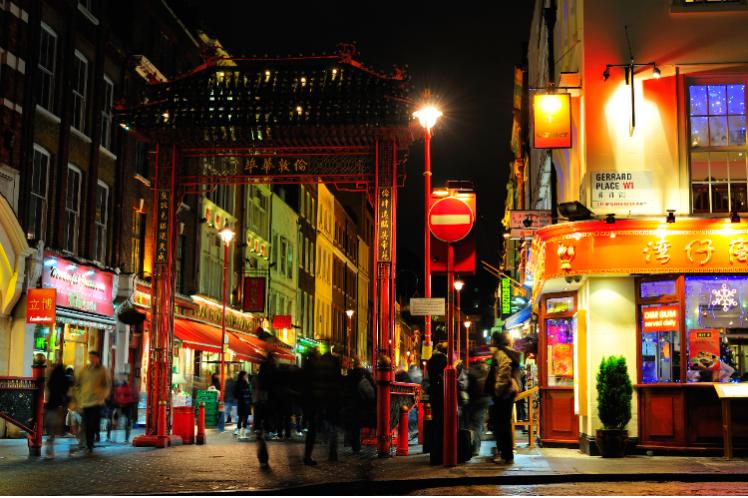

Chinatown, London (Credit: Parmorama / Alamy Stock Photo)

Chinatown, London (Credit: Parmorama / Alamy Stock Photo)

Now CCP gangs have been able to hide under the banner of anti-Chinese sentiment to inflict violence on those advocating for democracy, says Mark Sabah, director of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong. “There was a group of Hongkongers a couple of years ago in Chinatown in London,” he recalls, “where they started waving Hong Kong flags and chanting ‘free Hong Kong’, and a mass brawl broke out… and they were all holding signs saying ‘Stop Asian Hate’ while beating up Hongkongers.”

In recent days, security minister Tom Tugendhat announced that the Chinese Embassy claimed to have shut down all four Chinese police stations. While this came as an “enormous relief” to Alicia Kearns, chair of the China Research Group, she says we must remain vigilant. “The key thing will be for now is for us to work out what they replace it with,” she says, “because they will now be looking for a new way in which to achieve the same effect.”

But how can we know that the Chinese Embassy has really shut the stations?

“We can’t,” says Kearns simply. “Our entire relationship with China is: ‘trust but verify’. We want to take them at their word, but we have to assume that they are not necessarily telling the truth – we have to verify. So I’m sure the police will keep an eye and the China Research Group will certainly keep an eye.”

Lord Alton of Liverpool, a member of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, says the clarification from the security minister is welcome, but says “it beggars belief that they were able to operate for some time under the government’s nose at all”.

Now he says the government “should undertake a thorough review of the number of official and unofficial PRC diplomats and officials currently active in the UK, and ensure they are brought into parity with the number of diplomatic staff the UK has been permitted to have in China”.

Lord Alton of Liverpool (Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

Lord Alton of Liverpool (Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

While the government has spoken out, the intimidation tactics wielded by the CCP have left some UK institutions unsure of how to respond, says Sabah. He mentions that an event in the south of England, organised by Hongkongers in Britain, was shut down recently by the venue, because they “got spooked”.

Cheng, who founded Hongkongers in Britain, thinks that the venue withdrew its support because it came under pressure from members of the Chinese community.

“I think that they will be scared of some tell-tale reports,” he explains. “They actually have been reported by someone who may claim they are members … [who] said maybe: ‘we are Chinese, or we are living here peacefully, we don’t want to see other communities bring politics within our community.’”

When Cheng posted on social media to say the event had been cancelled, he says that CY Leung, the former chief executive of Hong Kong, reposted his tweet, agreeing that the venue had made the right decision.

Lam seems resigned when contemplating how the CCP may further influence life for Chinese nationals living in the UK. “Now I think they know they are being noticed,” he says. “They are keeping a lower profile. But the low profile doesn’t stop them from the continuous surveillance and harassment, that happens every day.”

The Chinese embassy in the UK was contacted for comment. In response to claims regarding Simon Cheng, it has previously told The Times his detention was “strictly in accordance with the law”, adding “the legal rights of all Chinese citizens, including overseas citizens, are guaranteed”. The embassy also directed The House to a comment from its spokesman in which he denied the existence of overseas police stations, stating: “China urges the UK to stop spreading disinformation, stop hyping up the issue, and stop smearing China.”