Driverless cars: the future of travel or a road to nowhere?

7 min read

The future of travel – or a fantasy on the road to nowhere? Sienna Rodgers explores the long and winding journey for driverless cars.

The self-driving revolution promises a panoply of utopian benefits: accidents reduced; jobs created; insurance premiums cut; domestic air travel made redundant; road traffic brought down; air quality improved; car parks reclaimed. The list goes on. What’s not to like?

“Robots don’t get distracted. Robots don’t have a bad day and get grumpy,” Ben Everitt, Conservative MP for Milton Keynes North, declared in a Westminster Hall debate last year. Driverless cars, he continued, “can help people with disabilities become more mobile, vitally improve access to employment and healthcare, give one million people in the United Kingdom better access to higher education and potentially unlock £8bn of value to our economy.”

Connected and autonomous vehicle (CAV) technology could create around 320,000 new jobs in the UK by 2030, Everitt told colleagues. No wonder ministers excitedly released a plan in August for the rollout of self-driving vehicles on UK roads by 2025, backed by £100m of government spending for research and help to kick-start commercial services.

But there are complex hurdles for driverless vehicles to overcome. Chief among them, according to enthusiasts, is public attitudes. “The cultural acceptance is probably going to be the biggest barrier to automating our transport networks,” Everitt, chair of the Connected and Automated Mobility All-Party Parliamentary Group, tells The House. “We need to regulate properly so that it happens safely, and make sure we do it in a way that is accepted by the public.”

The other significant barrier is liability, he says. “The tech is fine. It evolves and becomes more precise as we go along. Aside from culture, the most immediate barrier we’ve got is where the liability lies. Is it the driver? Is it the manufacturer? Is it the insurer? That’s the bit the government is working on solving at the moment, which, frankly, is the most fun bit.” Everitt is hosting discussions between MPs, civil servants, lawyers and insurance industry representatives to work on this emerging problem.

Robots don’t get distracted. Robots don’t have a bad day and get grumpy.

Everitt represents Milton Keynes North, where a grid system makes the 55-year-old city almost uniquely well-suited in the UK to CAVs – like cities in the United States such as San Francisco, where people can hail driverless cabs known as “robotaxis”. The MP says of his patch: “It is an ideal testbed for this kind of technology. But one of the issues we need to consider is: are we just proving this works in Milton Keynes?”

If Everitt is one of the keenest proponents of autonomous cars, Labour politician, transport specialist and author of Driverless Cars: On a Road to Nowhere Christian Wolmar is one of the most vocal sceptics. He believes the biggest stumbling block is not public attitudes or legal issues but something much more fundamental: the tech. “It’s very marginal, it’s costing a hell of a lot of money, it’s not getting anywhere fast, nobody particularly wants it – and yet the government is prepared to put quite a lot of money into it rather than improving the technology of bus services,” he tells The House.

“The technology is nearing a dead end. It will have limited use in specific situations, like an airport shuttle,” Wolmar says. (Driverless shuttles were trialled at Birmingham airport earlier this year.) “You’re not going to get this situation where most cars are driverless, and that was their ultimate aim.” He cites John Krafcik, chief executive of Google’s self-driving car project Waymo, who said in 2019 that fully autonomous cars – those able to drive in all conditions without human input – will never exist.

There are six levels of car automation: level zero, no automation; one, automation that allows feet off; two, hands off; three, eyes off; four, mind off; five, mind off with no restrictions on where the vehicle can go. Some say big tech companies have mistakenly focused on levels four and five, when levels one to three are more realistic.

Wolmar warns, however, that the lower levels present their own risks – namely deskilling drivers. Partial automation can cause confusion. The first CAV fatality took place in Arizona in 2018 when an Uber test driver in a semi-autonomous Volvo hit a pedestrian, 49-year-old Elaine Herzberg. Prosecutors said the car’s operator, Rafaela Vasquez, was streaming the TV show The Voice at the time; the defence said she was only listening to it. (Uber was not held responsible but has since abandoned its autonomous division.)

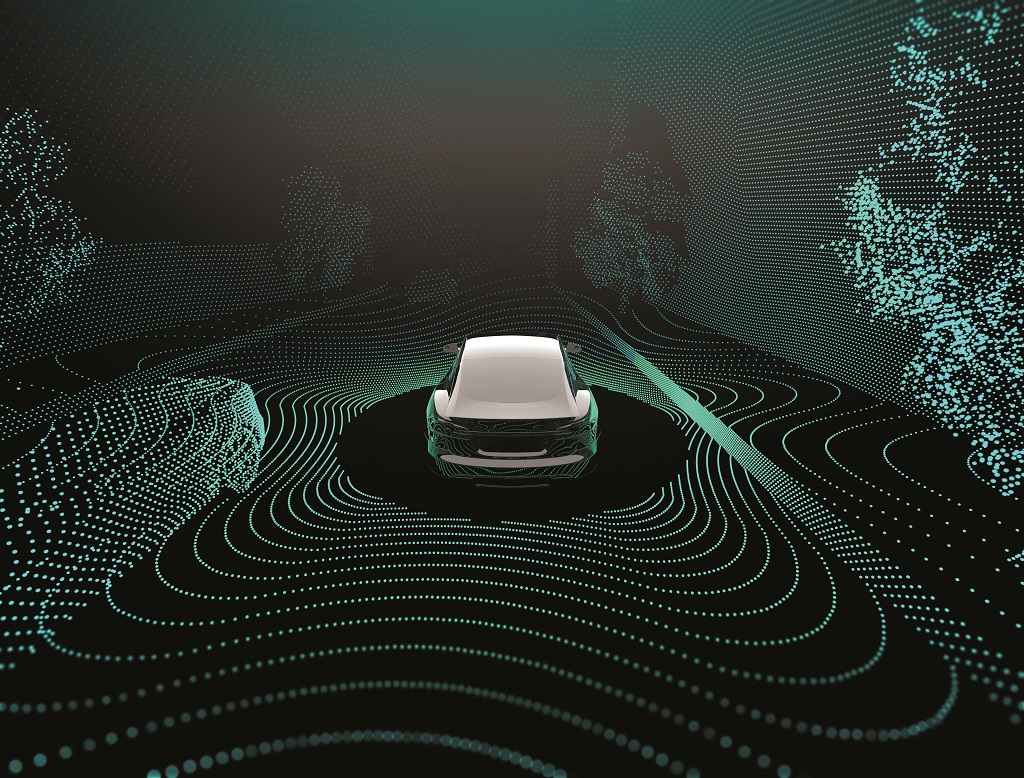

(Adobe Stock)

(Adobe Stock)

Accidents involving assisted driving are often discounted by automation advocates as human error. Critics counter that humans are always going to drive like humans; unless all normal cars are replaced in one fell swoop by fully driverless ones, the tension between the two cannot be waved away.

Given these obstacles, Wolmar wonders why the government is so enthusiastic about driverless cars. “Transport is a pretty boring, day-to-day issue,” he theorises, “whereas this notion of exciting technology, ‘we’re going to be at the vanguard of this,’ is what tempts them.”

Ruth Cadbury, a Labour MP on the Transport Committee, agrees: “We are only at the outset, but we have to be really careful of the unintended consequences of what looks like shiny, exciting, sexy, new technology.” She also raises concerns about partial automation. “I’m not convinced it is altogether safe. Does it provide false security to drivers?”

The Transport Committee launched an inquiry into self-driving vehicles in June and began taking oral evidence last week. MPs will look at their uses, the progress of trials, infrastructure, regulation, safety, effects on car ownership and the role of government. Although Cadbury maintains she will approach the sessions with an open mind, she plans to “challenge the evidence… quite rigorously”.

Greg Smith, a Conservative member of the committee, is also open-minded yet sceptical. “A lot of that comes from the inquiries we’ve already done as a select committee,” he says. “If we can’t get stopped vehicle detection on a smart motorway to work, you’ve got to conclude it’s very unlikely a car that drives itself is going to be safe… It only takes one camera sensor failure to lead to something catastrophic, potentially the loss of human life.”

We have to be really careful of the unintended consequences of what looks like shiny, exciting, sexy, new technology.

Committee chair Huw Merriman describes himself as “more on the excited side than the sceptical side”. And yet, considering whether assisted driving rather than fully driverless is the safest form of the new technology, he sounds unconvinced about the middle ground option. “If you’re riding a bicycle without a helmet, you’re less likely to get knocked off and – the theory goes – less likely to be injured than if you’re wearing a helmet because a driver of a car, as soon as they see someone riding a bike without a helmet on, they are much safer around it… We’re interested in the human behaviour side of this technology as well as the actual technology side.”

Perhaps the answer lies not in a compromise on levels of automation but on breadth of application. Giles Perkins of engineering consultancy WSP, who has helped Everitt’s APPG, runs a team immersed in the future of transportation and mobility. He appears enthusiastic: “One could see autonomous technologies being almost as radical for transportation as the introduction of the internet.”

Yet he stresses that the technology must be seen in terms of being useful in specific circumstances. “It’s not a blunt instrument you can apply and say, ‘in the future, everything will look like The Jetsons’.” He highlights the possibilities for shuttles, freight and last-mile delivery, which is already being changed in the UK by Starship Robots – small, six-wheeled vehicles that navigate streets autonomously delivering food and packages over short distances.

Many MPs are doubtful about the government’s target of getting driverless cars on UK roads by 2025. “It seems a bit of a stretch in terms of where we are right now,” Merriman says. “There is so much to plough through – the legal, the regulatory, the technology working, the public ultimately being assured that they’re confident with this.”

Automated vehicles will undoubtedly change transportation in the UK and may be hugely transformative in time. But for those hoping to forget traffic jams within the next few years, or ditch the school run and rely on automation to get the kids to class – hard luck.