Going digital: Will the public realise the value of digitising NHS data?

Doctor checks patient data on iPad (Credit: Mark Thomas / Alamy Stock Photo)

8 min read

The NHS is about to make it far easier for hospitals to share data, including patient records, in the latest stage of its digitisation drive. But is enough being done to win public backing for moves to realise its huge value, asks Sophie Church

For 75 years the National Health Service has been collecting our data. From records of GP appointments to details of prescribed medication, some of the most sensitive information concerning around 65 million people is on file.

These notes, essential to individual care, have enormous value both to improve the operation of the NHS and to those – including private companies – looking to develop new diagnostic techniques and therapies with the help of artificial intelligence (AI).

The NHS has been notoriously bad at building systems that realise these potential benefits. While politicians repeatedly insist that technology offers the prospect of huge savings and better care, the reality rarely, if ever, meets the ambition.

Now the NHS is on the brink of awarding a huge software contract that it says will allow NHS Trusts and integrated care systems to share data, including patient data, they already hold. Together with the NHS app and the rollout of electronic patient records to all hospitals in England by the end of 2025, are we finally on the cusp of a real digital revolution?

We’re all deeply suspicious of procurement now, precisely because of the pandemic; the favours done to people and so on

The most ambitious of these plans is the new federated data platform (FDP) – worth £480m – which is about to be tendered to a private company.

The platform is designed to overcome the problems that bedevil data sharing between Trusts with different IT systems. At a glance, staff will be able to access the number of available beds in a hospital, look at waiting lists and monitor medical supplies. It should make the health service more efficient for clinicians and patients, speeding, for example, the journey from cancer diagnosis to first treatment or to discharge. In a list of ‘frequently asked questions’ posted on the NHS website earlier this month it insists the FDP “will initially be focused on supporting five key NHS priorities” which it lists as elective recovery; care co-ordination; vaccination and immunisation; population health management; and supply chain management.

The NHS acknowledges, however, that this vast treasure trove of data could be used later for other purposes, although insists “no further uses will be allowed without further engagement with public, patient and stakeholder assurance and advisory groups”.

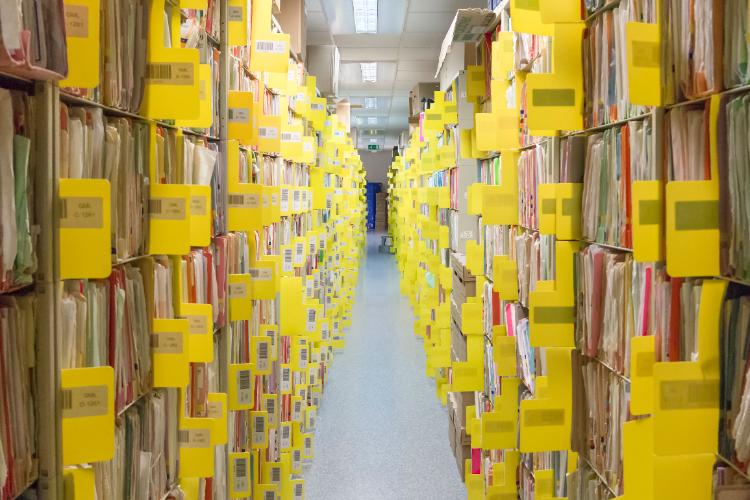

NHS data on file (Credit: ANDREW WALTERS / Alamy Stock Photo)

NHS data on file (Credit: ANDREW WALTERS / Alamy Stock Photo)

This engagement is way behind where it should be, according to a range of experts and watchdogs. But it is essential to keep the public onside regarding future access, as patients will only be able to opt out of sharing their data for research and planning, not for direct patient care. The NHS insists that new privacy protection software will ensure that only clinicians who need to see individual patient data will be able to do so, but others say much more needs to be done to prevent a backlash.

Labour peer Lord Knight says failing to understand the benefits of having a digital data depot comes down to the public’s lack of awareness about data. “There aren’t that many people who are fully up to speed … on what data is collected, under what consent regimes, how that data becomes training data for AI … it’s difficult,” he says.

Steve Barclay, Health Secretary, speaking at a fringe event at Conservative Party Conference, says we are standing on the brink of a great opportunity, not a cataclysmic threat. He questions why the public would be happy to share health data with certain bodies but not others.

“There’ll be people wearing Apple watches and sharing their health data with California without thinking about it,” he says. “And yet [when it comes to] the NHS, which they love, they’re much more suspicious about sharing data.”

Lord Knight agrees there is a disconnect in our attitude to data sharing. He says that if we’re willing to share our data with retailers – in return for discounts, for instance – surely we can support sharing health data, too.

“Maybe we would be willing to get a better health service [with] better treatment, more personalisation and better understanding of our own individual cancer, or whatever, in exchange for sharing our data,” he suggests, while recognising that “the step-change in trust needs to be massive”.

Barclay hopes the NHS app can empower the public. As an example, he says: “The patient can decide to share their data with an AI firm because they’ve got a family history [of a condition] and they want someone to look at that.”

However, the risks of getting ahead of the public are real. In 2015, the Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust gave Google’s DeepMind access to vast amounts of patient data. Legal action was taken on behalf of 1.6 million people, though the claim was eventually dismissed by the High Court.

The public may retaliate by choosing not to share their data with the NHS at all, warns Carol Monaghan, vice-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Artificial Intelligence. In this case, no one wins.

“It comes down to the key aspect of who owns the data. If that data is passed on to a third party, the patient starts to lose ownership,” she says. “It is absolutely right that patients are able to opt out. But if we’re using data to try to improve efficiencies, or trying to develop better systems, when we start getting opt-outs, we start losing the granularity that really makes it worth doing.”

Perhaps, though, says Liberal Democrat peer Lord Clement-Jones, the reason for public mistrust lies in government procurement processes, more than the end result. “We’re all deeply suspicious of procurement now, precisely because of the pandemic; the favours done to people and so on.”

NHS app (Credit: GSTech / Alamy Stock Photo)

NHS app (Credit: GSTech / Alamy Stock Photo)

Lord Knight agrees, suggesting that “having the governance around the sharing of our data being held at arm’s length from government seems a sensible step to take”.

There are signs that trust in the current FDP procurement process is already dwindling. Though UK data technology company Quantexa is also said to be in the running to win the contract, in a consortium with IBM, critics have accused the government of giving preferential treatment to Palantir Technologies, an American software company whose platform, Foundry, helped track Covid-19 data during the pandemic. The NHS insists there is no frontrunner and that it has worked with No 10 to ensure the tendering process is fair. The contract is expected to be awarded in the coming weeks.

“I think when Palantir were given … the contract for the Covid data store,” Monaghan says, “it gave them a foot in the door, and you remember that was a contract that was awarded without going out to tender.” Now, she says, the public “have a right to know some of the process” in how the contract has been awarded.

Maybe we would be willing to get a better health service… in exchange for sharing our data [but] the step-change in trust needs to be massive

As it stands, answering the question of who decides what happens to the data once it is on the platform is proving difficult, and more needs to be done, says England’s national data guardian, Dr Nicola Byrne.

“The programme needs to be very clear … that the tech company doesn’t have that kind of access,” Byrne says. “There may be access they need for the management of the system, or security checks, or whatever. But the company themselves won’t be able to access and use any of that data.”

Lord Clement-Jones holds legislators responsible for breeding concern about data privacy. “If you look at the new Data Protection [and Digital Information (No. 2)] Bill,” he says, “they seem to be redefining the meaning of personal data, and changing things like legitimate interest and so on. So … it’s mood music that data protection is being watered down.”

However, Lord Holmes thinks there are elements of the bill that could be amended in the Lords to ensure the public is still protected. Specifically, he mentions pseudonymisation: the act of removing or transforming information that identifies an individual. Pseudonymisation has been redefined by the Commons, meaning the public’s data may be less protected and is, he says, “one of the areas I’ll be bringing up and wanting to delve into”.

For now, Lord Holmes says it is absolutely critical that government fosters greater public debate around data. To do so, he says we need only look to the recent past. He references the Warnock Committee, which communicated with the public on in vitro fertilisation, enabling people “to feel connected” to what, at the time, seemed a proposition of “science fiction”.

Barclay agrees more needs to be done to communicate with the public. “I think, just as with the debate on vaccines, there will always be some people who talk up the threats, rather than talk about the benefits of early diagnosis and the benefits to their health,” he says. “We have not enabled that sort of empowering of the patient on the health side. And I think there’s a huge opportunity [to do so].”