Losing the plot: navigating the truth behind GPS jamming

13 min read

From the Baltic to the Mediterranean, GPS jamming is a growing problem for both the military and airlines – but is it a real threat to safety or just exposing a lack of resilience in commercial operations? Sally Dawson reports on an issue the industry appears surprisingly reluctant to discuss

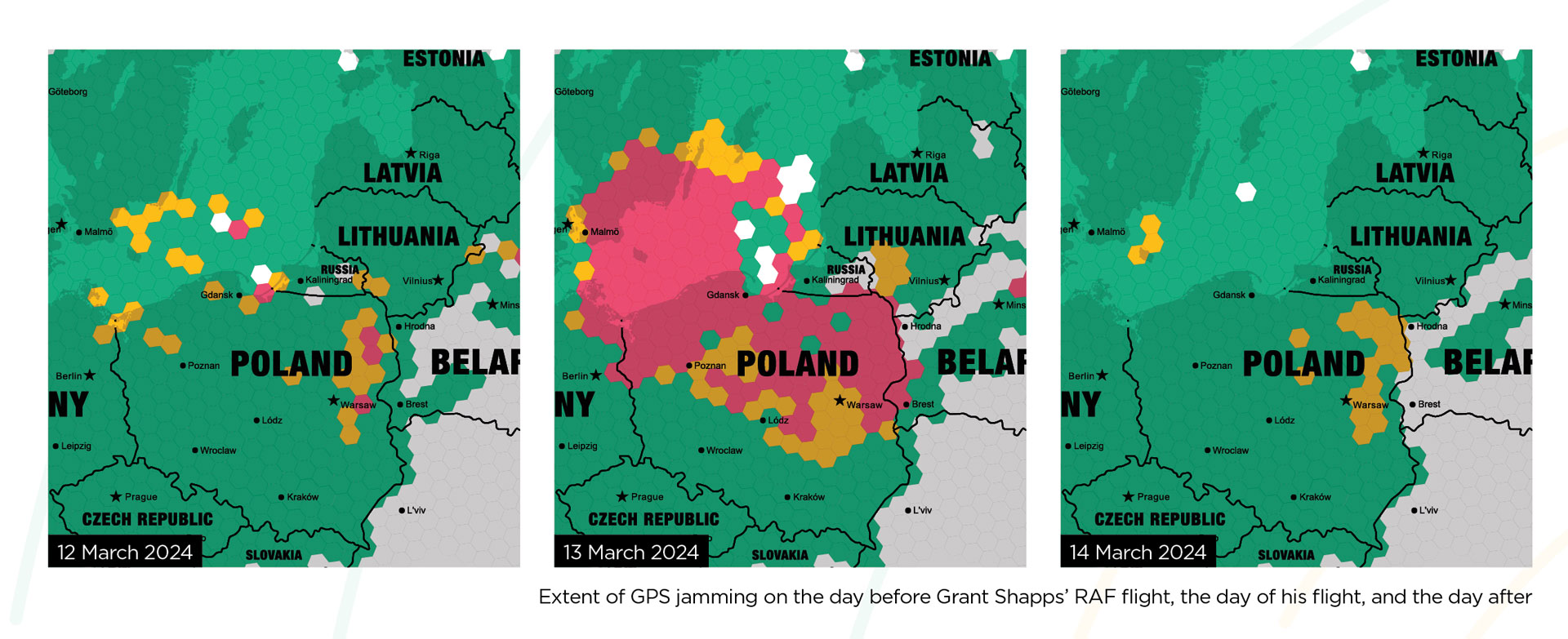

It made for an arresting headline: “Russia jams signal of RAF plane carrying Grant Shapps.”

The disruption of the plane’s global positioning system (GPS), which it uses for navigation, was witnessed by a group of journalists travelling with the Defence Secretary in mid-March.

Naturally enough, the suspected attack (which occurred near the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad) has led to increased interest in the topic.

The ‘jamming’ of a GPS signal – also known as ‘scrambling’ – is the deliberate blocking of satellite communications by an external source, forcing aircraft to rely on their other navigations systems. Jamming has a less frequently reported and potentially more dangerous sibling, ‘GPS spoofing’, where the plane – or ship – believes it is somewhere else altogether (more effective when it is dark).

In parts of the world, GPS interference is a daily occurrence.

Sandwiched between Lithuania and Poland on the Baltic coast, Kaliningrad is suspected of blocking the GPS of both commercial and military aircraft flying in the area.

According to research by the website GPSJAM.org in collaboration with The Sun, more than 46,000 aircraft have experienced interference with their sat-nav in the Baltic Sea region, between August 2023 and March this year.

These attacks are widely believed to be Russian in origin and rooted in Vladimir Putin’s displeasure at recent Nato exercises in Poland, and an attempt to disrupt airborne Western military assistance to Ukraine. Former RAF air vice-marshal Sean Bell says the West’s military assistance is not just about supplying weapons: “There are aircraft flying up and down the borders of Ukraine in international airspace that are using Nato assets to look across the border into Ukraine. They are eyes and they are ears, and they are hoovering up intelligence. And they are evidently passing that to the Ukrainians.”

Russia, he says, “will be very hacked off” at its inability to stop this assistance. But that hasn’t stopped it making its frustrations clear, shooting down a drone in the same month as the Shapps incident and firing at an RAF surveillance plane in 2022.

I’ve got lots of ex-military colleagues who are now flying for [commercial] airlines who say there’s a lot of jamming going on

GPS jamming, however, tends to be a very blunt instrument: “Bear in mind that the GPS signal is coming from satellites hundreds of miles away, it’s an incredibly weak signal and, therefore, it is not difficult to jam.

“I’ve got lots of ex-military colleagues who are now flying for [commercial] airlines who say there’s a lot of jamming going on.”

Given that there are so many incidents of GPS jamming around the Kaliningrad area, was Grant Shapps’ RAF flight just a random victim of an everyday occurrence – or was his plane deliberately targeted that day?

“If I was Grant Shapps and I know I’ve never got enough money in defence, using the fact that my aircraft has been jammed when it’s packed full of journalists, who probably now feel vulnerable because they’re being targeted – what a great way to get a story out,” Bell says.

The Shapps story may have been a little overcooked but that doesn’t mean GPS interference isn’t an increasing issue in both military and civilian fields.

Just how dangerous is it? And are commercial flights more vulnerable?

A satellite enthusiast with a pilot’s licence, Conservative MP Mark Garnier says the navigation systems on modern commercial aircraft are highly sophisticated. “So if it goes wrong, you’ve always got a second choice, and you’ve got a third choice. So aircraft won’t fall out of the sky if you switch off the sat-nav because aircraft are designed to have redundant systems,” he says.

Bell, the host of defence podcast RedMatrix, says commercial planes also fly at higher altitudes than military aircraft: “They’re generally at sort of 30,000 ft, five miles up. So you need quite a powerful jammer to jam the signal, because they’re obviously closer to the satellites than we are.”

Might a plane be more susceptible when it is lower in the sky, at take-off and descent, for example? In late April a Finnish commercial airline took the decision to suspend its daily flights from Helsinki to Estonia’s Tartu airport until 1 June, following two incidents where its aircraft were unable to land due to GPS jamming.

“The approach methods currently used at Tartu airport are based on a GPS signal,” Finnair said when it announced the suspension. “GPS interference, which is quite common in the area, affects the usability of this approach method and can therefore prevent the aircraft from approaching and landing.”

The aim of the one-month suspension, the airline said, was to “build approach methods” at Tartu airport “that enable a safe and smooth operation of flights without a GPS signal”.

Estonian foreign minister Margus Tsahkna did not hold back in his opinion of who was responsible, blaming “Russia’s hostile activities”. “Such actions are a hybrid attack and are a threat to our people and security, and we will not tolerate them,” he added.

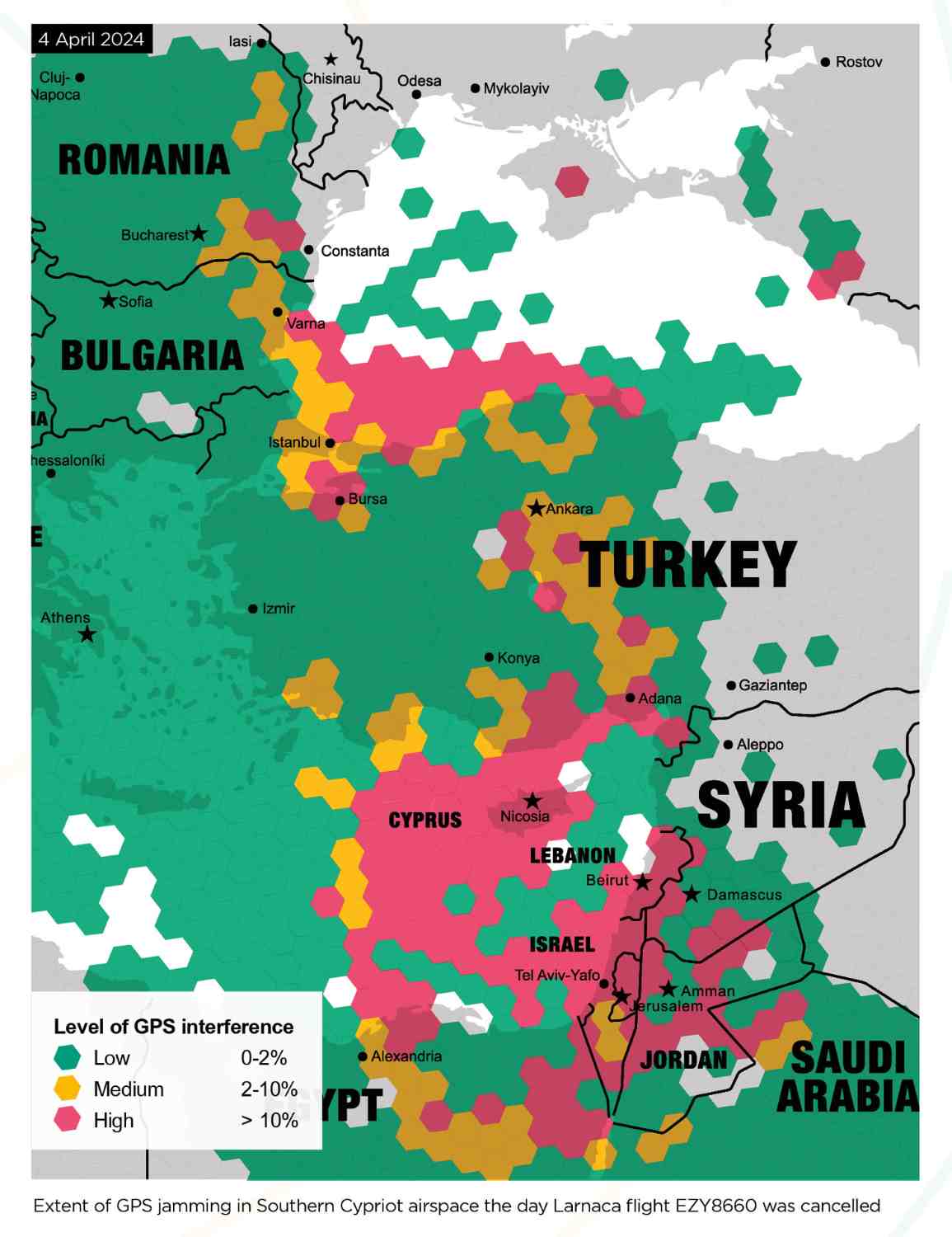

Both the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean areas also appear to be experiencing high levels of GPS interference. An International Air Transport Association report on interference to global navigation satellite systems, which include the USA’s GPS and EU’s Galileo, from March 2021 found two major geographical clusters of interference: one extending from eastern Turkish airspace to Iraq, Iran, and Armenia; another running from Southern Cypriot airspace to Egypt, Lebanon and Israel.

Regulators and operators in the United Kingdom appear desperate to downplay the impact, however. When asked to comment on whether the current rise in GPS jamming was impacting the safety of airline operations, the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) said GPS jamming is “relatively rare globally” and does not directly impact the navigation of an aircraft. “It is a known issue and does not suggest an aircraft has been jammed deliberately.”

As GPS forms only part of a commercial plane’s navigation system, it says, there is “no over-reliance” on a single source of data, meaning “aircraft are not getting ‘lost’ or deviated in the sky”. “The GPS jamming and spoofing we have seen near to conflict zones is primarily a by-product of activity related to the conflicts, rather than deliberate actions to interfere with global commercial air transport operations.”

When asked how frequently Ryanair flights had experienced deliberate interference with their GPS navigation systems, a company spokesperson told The House: “In recent years there has been a rise in intermittent GPS interference, which has affected all airlines.

“Ryanair aircraft have multiple systems to identify aircraft location, including GPS. If any of the location systems, such as GPS, are not functioning, then the crew, as part of standard operating procedures, switch to one of the alternate systems.”

When approached for comment by The House about how often easyJet flights had experienced interference with their GPS and whether it had resulted in any flight cancellations, an easyJet spokesperson responded: “There are multiple navigation systems onboard commercial aircraft as well as procedures in place which mitigate against issues with GPS that can occur for various reasons and for your understanding no flights have been cancelled as a result.”

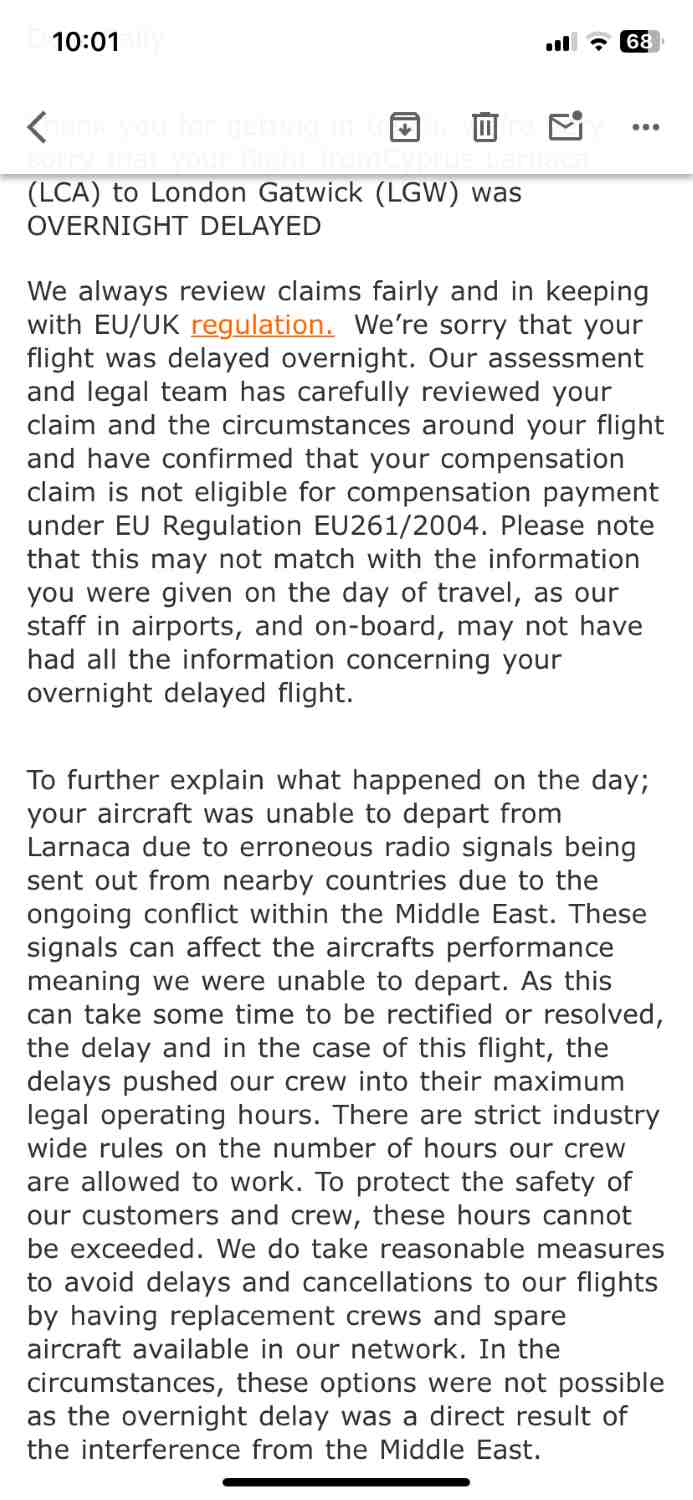

However, The House magazine can reveal that one easyJet flight last month – EZY8660 from Larnaca to Gatwick – was due to depart at 10.40pm on Thursday 4 April but was cancelled, with GPS jamming given as the primary cause.

“Your aircraft was unable to depart from Larnaca due to erroneous radio signals being sent out from nearby countries due to the ongoing conflict within the Middle East,” easyJet customer services said on April 26. “These signals can affect the aircraft’s performance meaning we were unable to depart.”

Original easyJet customer services' email explaining the cancellation of flight EZY8660

Original easyJet customer services' email explaining the cancellation of flight EZY8660

When The House asked easyJet to account for this contradiction, the company insisted that the reasons for the delay had not been “clearly explained” and continued to claim that no flights had been “directly cancelled” by GPS jamming.

The easyJet spokesperson said that while the aircraft had initially been inspected for a suspected technical issue “as a precaution only”, the flight was delayed overnight due to an “air traffic management issue” and the subsequent delay in departing had resulted in the crew “reaching their safety regulated operating hours”

“We take our consumer responsibilities seriously and always pay compensation when it is due,” easyJet added.

If the Russians are believed to be behind the attacks around Kaliningrad, it is less clear who is responsible for attacks in the eastern Mediterranean, and what their motive might be.

With a Russian presence in Syria, plus the ongoing conflict in Gaza, experts are divided as to who could be responsible, some even speculating it could be an operational side effect of Israel’s Iron Dome. In March, Lebanon announced it was making an urgent complaint to the UN Security Council, accusing Israel of “violating its sovereignty” by jamming Lebanese navigation systems. In a statement, Lebanon’s foreign ministry said: “Lebanon also holds Israel internationally responsible for the consequences of any accident or disaster caused by Israel’s deliberate policy of jamming air and ground navigation systems and deliberately disrupting signal receiving and transmitting devices.”

GPS interference in the region extended further than just with aircraft operations that month, with Business Insider, Lebanese daily L’Orient-Le Jour and Haaretz reporting interference with the location data on the dating app Tinder – with more than 60 per cent of the matches offered to Lebanese citizens being Israeli nationals and vice versa. Haaretz had previously reported in October that the IDF had increased GPS jamming in the region to thwart drone attacks by Hamas and Hezbollah.

In Southern Cyprus’ immediate airspace, according to Bell the issue is the proximity of RAF Akrotiri, roughly 55 miles from Larnaca airport. “Akrotiri has for a long time been a forward operating location for the British military. But also the US have operated out of there for many years as well,” he says.

In Southern Cyprus’ immediate airspace, according to Bell the issue is the proximity of RAF Akrotiri, roughly 55 miles from Larnaca airport. “Akrotiri has for a long time been a forward operating location for the British military. But also the US have operated out of there for many years as well,” he says.

Located on the eastern flank of Nato, many of its ‘assets’ are launched from Akrotiri. “And those assets have been involved in targeting the Houthis in Yemen. They’ve been used to do the protection for Israel when Iran fired 331 missiles and drones at the country,” Bell says. “So Cyprus itself is an important base for supporting the Western military efforts, and therefore will undoubtedly be a focus for Russian meddling.”

If interference is causing delays or cancellations to commercial flights, it appears that the financial compensation implications may nonetheless be minimal. The UK’s largest travel association, Abta, says whether compensation is payable depends on CAA rules on what caused the delay – if it wasn’t the airline’s fault, compensation is not payable. According to its website, delays caused by things like extreme weather, airport or air traffic control strikes or other ‘extraordinary circumstances’ are “not eligible for compensation”.

Bell agrees with the airlines that GPS jamming is not a real threat: “If there was a credible threat to life, then this would have all been in the newspapers for months, if not years. It’s an inconvenience.

A CAA spokesperson told The House that if an airline claims ‘extraordinary circumstances’ to defend not paying compensation, then this is “typically” something that a court, an alternative dispute resolution body or the CAA’s passenger advice complaints team (Pact) can consider, though they added: “We’re not aware of any cases in which Pact have got involved on GPS jamming.”

Regardless of whether an airline would be liable for compensation payouts, there are other financial implication of delays on airlines’ operational costs. “Bear in mind, easyJet would not want an aircraft in the wrong place,” says Garnier. “That’s a really important point – that aircraft now wouldn’t be earning its money coming back to Larnaca from Gatwick or the following day, because it’s now in the wrong place. And that’s bad for easyJet.”

[With] crew duty time, if you’re running people right up to the limit, if anything goes wrong, then you’re going to have to cancel

Bell says most of the crews now are operating right on the limits of crew duty. This means that thanks to airlines’ tight scheduling it doesn’t take more than an hour’s delay for a cancellation to happen: “Now, in such circumstances, who do you blame?”

Acknowledging it is very difficult to ever know the full truth of the cause of a flight cancellation, Bell says it’s rare that GPS interference would stop an aircraft taking off. But pilots, says Garnier, don’t take risks: “You can make a judgment decision to fly without sat-nav, but if you’ve got no sat-nav, and you’ve got no horizon because its nighttime… even if the pilot maybe hadn’t gone past the amount of hours you can be awake, they might have just taken a decision that just wasn’t worth the risk.”

While the rules around crew duty are “understandably” tight, says Bell, in his experience the airlines try to “wring every last ounce out of their resources”: “And therefore [with] crew duty time, if you’re running people right up to the limit, if anything goes wrong, then you’re going to have to cancel.”

Airlines, he says, will always look to blame somebody else. “They’re a business after all, at the end of the day, if they can run it very tight… and by having the minimum number of crews who work the maximum number of hours, that’s the aim to make the airline as profitable as possible.”

Describing GPS jamming as more of a "distraction than a significant safety threat", the trade union for UK pilots, BALPA told The House that "in the grander scheme of flight safety, issues such as the threat of removing flight crew from the flight deck (as is being considered via reduced crew operations concepts) and fatiguing rosters are of more concern”.

Whether compensation becomes payable if a flight initially affected by jamming was ultimately cancelled due to operational reasons – if the airline did not have the necessary crew to replace staff who had reached the end of their safe working hours – appears to be a grey area. A CAA spokesperson said whether an airline can rely on the extraordinary-circumstances exemption is “often determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the facts”.

With tight profit margins and rising costs, such as fuel inflation, is GPS jamming merely exposing how airlines frequently do not have the necessary replacement crews and spare aircraft capacity in their networks? The trouble with running an airline with so little flexibility in its operations, Bell says, is that it takes away resilience. The real challenge of GPS jamming may not be the threat to safety but to the reliability of commercial airline operations. “And therefore,” Bell asks, “how do you manage resilience?”

While there was welcome news last week that a collaboration between UK companies had successfully carried out its first airborne test of a new un-jammable navigation system using quantum technology, the new system is believed to be at least a decade away before it will be ready to use.

With no end in sight to the conflicts in Ukraine and in the Middle East, GPS jamming may be something that airlines have to learn to live with for years to come.