Morning again: marking 40 years since Reagan's re-election

Ronald Reagan with Margaret Thatcher at the White House, Washington DC | Image by: dpa picture alliance / Alamy Stock Photo

Mark White, HW Brands, Iwan Morgan and Anthony Eames

9 min read

As the US enters uncharted territory following a tense presidential election, historians will gather next week in Westminster to mark 40 years since Ronald Reagan was re-elected to the White House. Mark White, HW Brands, Iwan Morgan and Anthony Eames preview the event below

Ronald Reagan in American history

After a long period of almost complete Democratic Party dominance of the US presidency, beginning with the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, there was a conservative reaction at the grassroots that became apparent, at the presidential level, with the election of Richard Nixon in 1968. The historical significance of the election of Ronald Reagan, the most ideologically conservative president since the 1920s, was that it represented the culmination of this conservative shift in American politics and society – a trend evident elsewhere, as with the election of Margaret Thatcher as UK prime minister the year before.

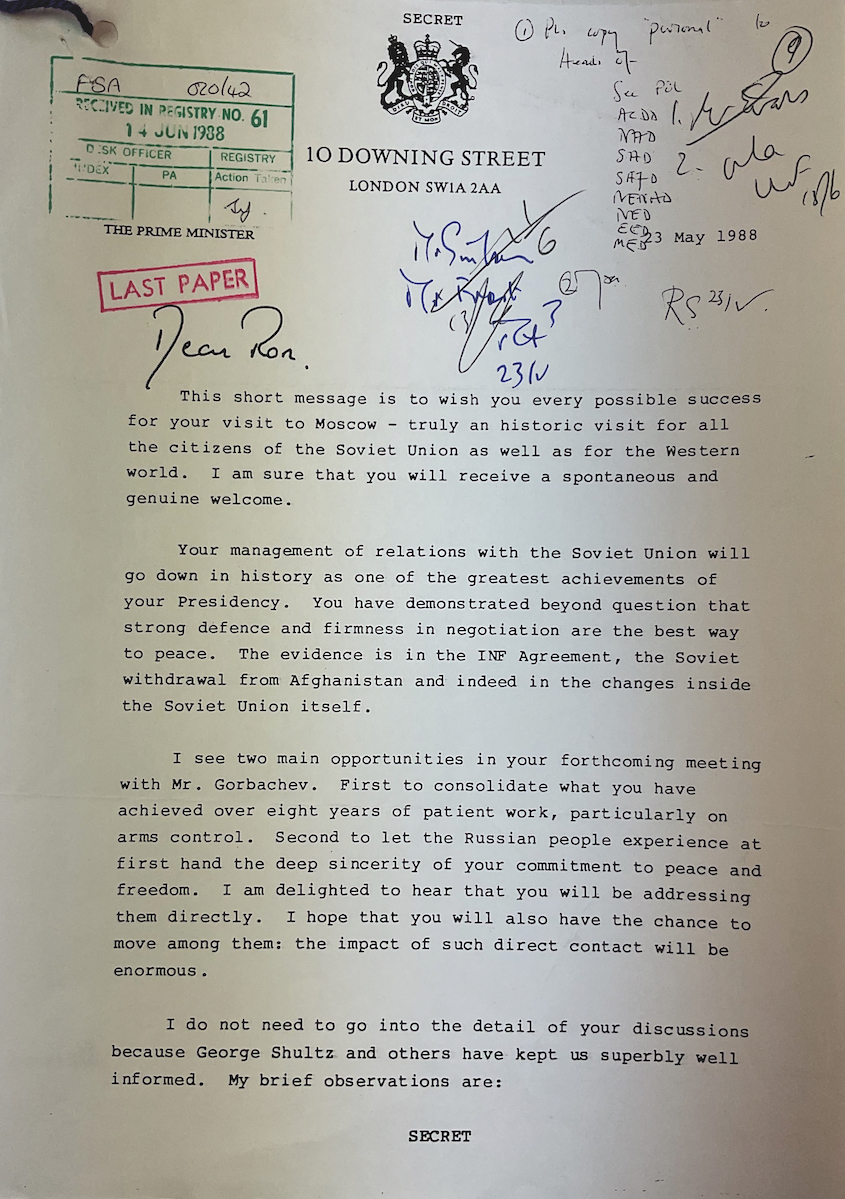

Letter from Thatcher to Reagan ahead of his visit to Moscow May 1988

Letter from Thatcher to Reagan ahead of his visit to Moscow May 1988

In the realm of foreign affairs, Reagan’s presidency – paradoxically, given the hard-line anti-communist rhetoric he often employed in his first term as well as his combative policies in Central America – marked the beginning of the end of the cold war. Four summit meetings with his Soviet counterpart Mikhail Gorbachev revealed a genuine chemistry between the two men and led to marked improvement in Soviet-American relations. And it wasn’t just talk. In 1987 they signed the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, the first accord to reduce superpower nuclear arsenals. An important question for historians is the extent to which Reagan deserves the credit for ending the cold war. Did his initial toughness and military build-up compel a more accommodating approach from the Soviets, or was it Gorbachev who was largely responsible for the rapprochement between Moscow and Washington?

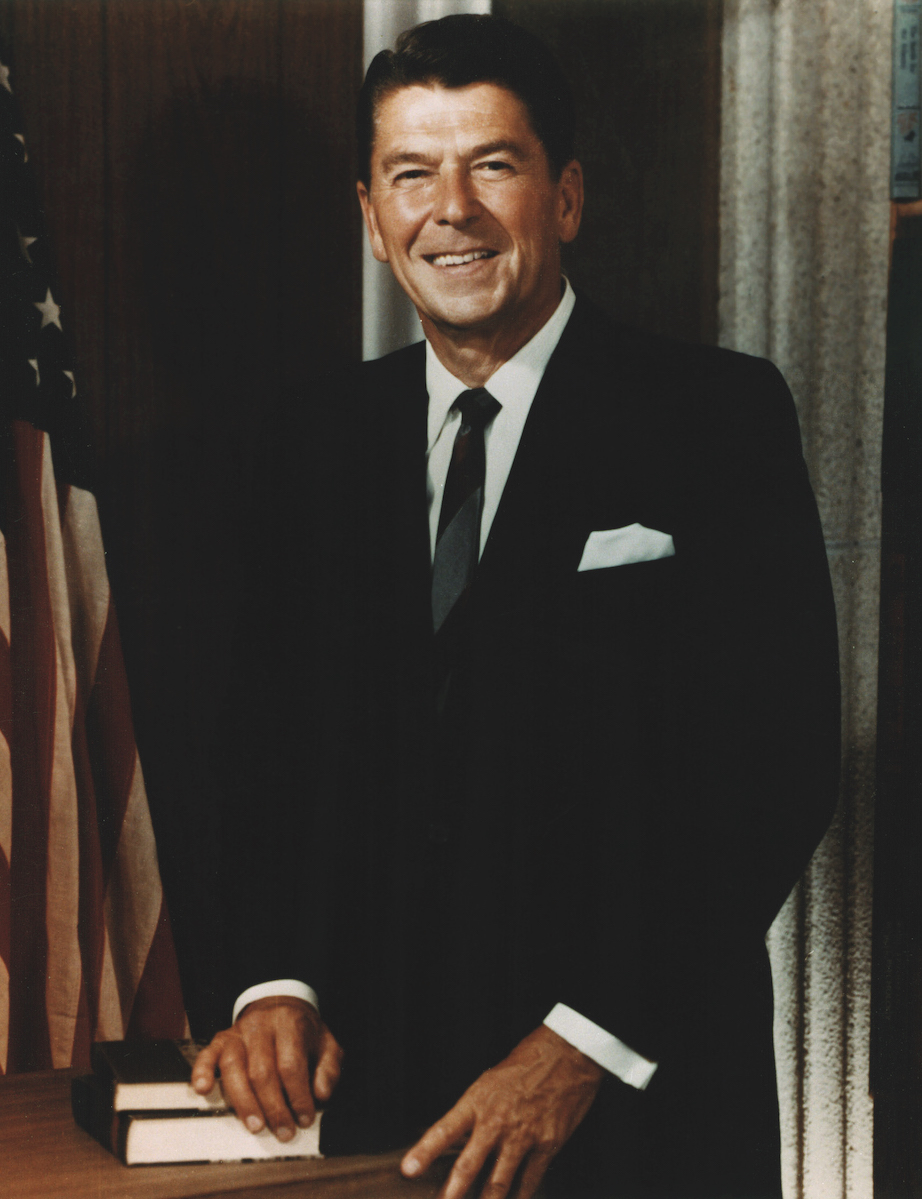

Reagan’s presidency had another significance: the linking of the worlds of politics and celebrity. For many years he had been a Hollywood actor. When one considers the Kennedys’ close ties to Hollywood, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s election as governor of California, and the election of Donald Trump (known to most Americans as a TV personality) to the White House, Reagan’s ascent to the presidency has been part of an identifiable trend. For Reagan, his acting background was of immense political benefit. He was a fluent and lucid communicator and had a likeable personality, and this contributed to his popularity and political success in the 1980s, not least his remarkable landslide re-election victory 40 years ago when he carried almost every state in the union.

Mark White is director of the London POTUS Group and professor of history at Queen Mary, University of London

Rehearsing the presidency

Ronald Reagan would not have become president had he been a better actor. But he was a better president for having been an actor.

Hollywood, not Washington, was the dream of the boy growing up in small-town Illinois in the 1910s. He later recalled the comfort he drew from being on stage for skits at his mother’s church. His father was an alcoholic who made the family home an unsettling place; the stage, at church and later in school, became his refuge. After college he worked in radio while getting up the nerve to take a screen test. The camera liked him, and he signed his first film contract in 1937. He learnt his craft and gained a reputation as a professional. He knew his lines and hit his marks. He could dance and tell a joke. Yet he never became a star. His face and persona were pleasant but not arresting. He could play the hero’s best friend but not the hero.

By the mid-1940s he was getting fewer and less engaging roles. He became involved in industry politics, eventually as head of the Screen Actors Guild. In that position he encountered real politics, when Congress pursued reports of communist infiltration of Hollywood. He discovered an aptitude for speaking without a script. He ventured into television when the new medium was entering American homes in the 1950s. As host of a weekly series of television dramas sponsored by General Electric (GE), he became one of the most recognisable faces in the country. Part of his job entailed travelling the country as a spokesperson for GE and the conservative values the company stood for.

He drifted away from the Democratic Party of his young adulthood and toward the Republican Party of Dwight Eisenhower and Barry Goldwater. In the early 1960s he made the switch official. A televised speech for Goldwater in 1964 received rave reviews and prompted calls for Reagan himself to run for president. He auditioned in California, running for governor. He won once and then again. In 1976 he challenged incumbent president Gerald Ford for the Republican nomination. He came close but lost. He tried once more in 1980 and won. In the general election he defeated Jimmy Carter.

Successful presidents combine substance with style; policy with performance. People disagreed about his policies, but few deny that he performed the presidency – as head of government and head of state, as high priest of America’s secular rituals, as cheerleader- in-chief and consoler-in-chief – better than anyone since Franklin Roosevelt. He inhabited the role as if he’d rehearsed it for life.

HW Brands is professor and the Jack S Blanton Sr chair in history at the University of Texas at Austin

The Reagan revolution

The so-called Reagan revolution is a convenient alliteration that exaggerates the scale of conservative transformation in 1980s America. Ronald Reagan came to the White House promising a Republican agenda of tax reduction, smaller government, and social programme retrenchment to restore an economy supposedly laid low by 50 years of big-government liberalism under the hitherto ascendant Democrats. It is worth considering his success on this score.

The greatest economic policy achievement of the 1980s was the conquest of hyper-inflation, running at 13 per cent in Jimmy Carter’s final year, largely achieved through the monetarist strategy of the Paul Volcker-led Federal Reserve – albeit at the cost of the worst recession since the 1930s from 1981 to 1982. Reagan’s Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 certainly helped to accelerate post-recession economic growth, but its diminution of Federal revenue was a critical factor – in combination with the loss of tax receipts from the recession and the administration’s massive expansion of defence spending – in generating the record peacetime budget deficits that were a feature of the 1980s. Reagan disappointed conservatives by promoting revenue-enhancing tax increases from 1982 to 1984 to shrink the deficit. He also had some success in reducing discretionary domestic spending but nowhere near enough to restore fiscal solvency. The massive entitlement programme economies required for this were unacceptable to most congressional Republicans, let alone almost every Democratic legislator. Meanwhile, the Reagan administration’s efforts to institute wide-ranging deregulation encountered bureaucratic resistance or ran into unforeseen difficulties.

Accordingly, Reagan’s achievements in domestic policy terms fell short of conservative expectations, but this does not detract from his historical significance. The Reagan revolution’s real success was in changing the terms of political debate: the liberal ascendancy engendered by the New Deal envisaged government as the solution to the nation’s problems, but Reagan succeeded in popularising the notion that government itself was the problem not the solution.

Iwan Morgan is emeritus professor at UCL and presidential scholar

Reagan's cold war and the power of ideas

Reflections by public intellectuals on Ronald Reagan’s cold war grand strategy often leave one wanting more. Pundits and the press habitually draw a singular, shallow message from Reagan’s rhetorical legacy – that it is better to be stronger than your enemy than weaker. This reductive view of Reagan’s “peace through strength” programme misleads, suggesting that Reagan viewed the world in terms of realpolitik and the search for power rather than through the lens of ideas. Such interpretations of Reagan’s peace through strength programme offer no real guidance for policymakers in the West looking to Reagan’s record for insights on how to confront Chinese and Russian ambitions to reset the world order in our current era of rapid technological advancement and disorientation of social networks and political geography.

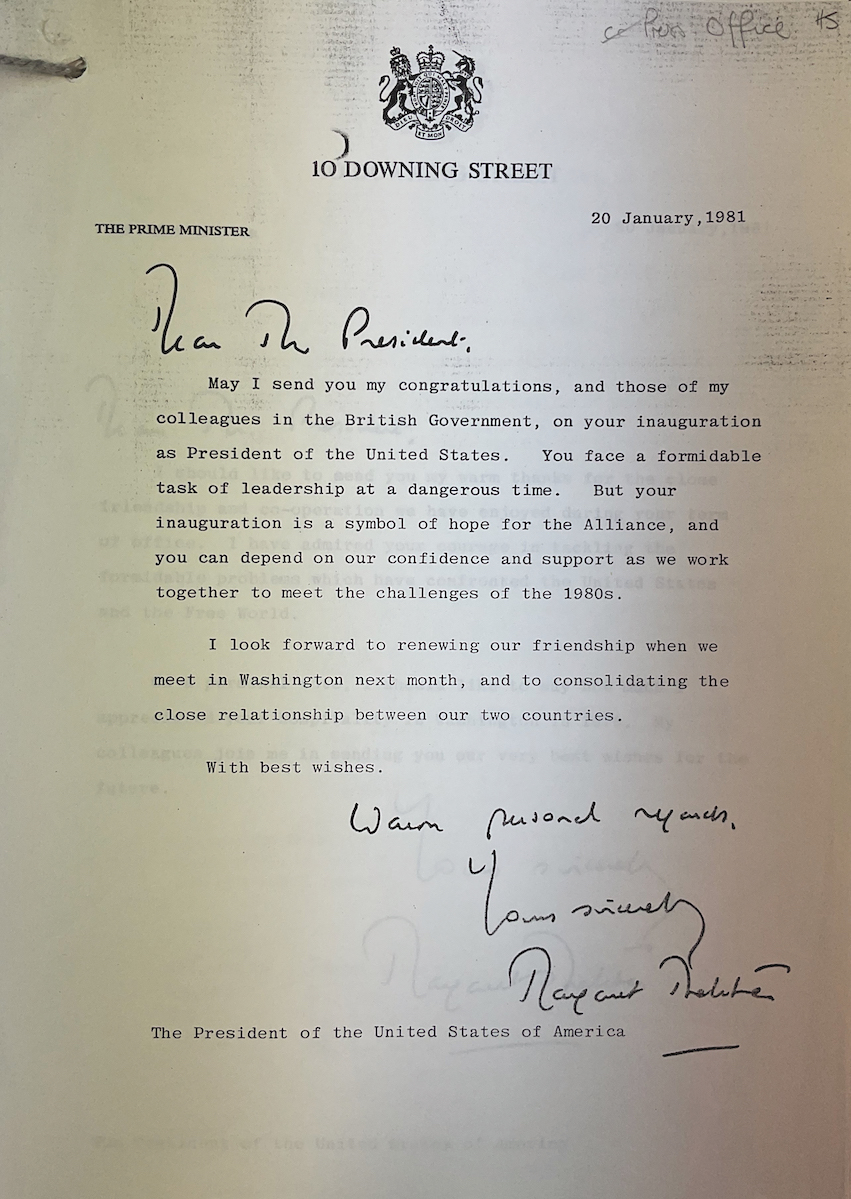

Letter from Thatcher to Reagan congratulating him on election victory 1981

Letter from Thatcher to Reagan congratulating him on election victory 1981

If Ronald Reagan were to pen a how-to manual on grand strategy for those interested in a deeper reading of peace through strength, one could expect chapters on each of the following: democracy promotion and human rights; arms control and nuclear abolition; investment in military force and military morale; public diplomacy and assertion of moral authority; economic warfare and recovery through free and fair trade; and alliance management and engagement with adversaries. What would set Reagan apart would be the introduction to the manual – a vision of how these points of focus come together in an executable strategy for restoring western predominance.

No need for hypotheticals. Reagan laid out his vision at Westminster on 8 June 1982. Hailed by the then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, as putting “freedom on the offensive”, Reagan’s greatest strengths were apparent – specifically his ability to establish foreign policy priorities and follow a proactive rather than reactive course. Those abilities stem directly from Reagan’s belief that the competition of ideas animated the international system, not realism. To draw the practical lessons from Reagan’s foreign policy, one first needs to draw the aspirational, that the “ultimate determinant in the struggle now going on for the world will not be bombs and rockets, but a test of wills and ideas, a trial of spiritual resolve”.

Anthony Eames is director of scholarly initiatives at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute

To mark the 40th anniversary of Ronald Reagan’s 1984 re-election as US president, the British-American Parliamentary Group, the London POTUS Group, and the Archives and History APPG, with the kind support of The National Archives, have organised a special event on Tuesday 19 November at 6pm in the State Rooms, Speaker’s House, House of Commons, by kind permission of Mr Speaker, The Rt Hon Sir Lindsay Hoyle, MP. A panel, discussing Reagan’s legacy, will comprise The Lord Moore of Etchingham, professor Iwan Morgan and Dr Anthony Eames. The event will be introduced by Chris Evans MP for Caerphilly, co-chair of the Archives and History APPG. There will be a curated display of documents from The National Archives at the event, which will shed light on key developments in the Reagan years, including the British government’s relationship with the Reagan administration.

RSVP to Hannah Mitchell at the BAPG mitchellhk@parliament.uk

As there is very limited space at the venue, we will have to restrict the event on a first come, first served basis.