Oneweb: Will the UK's gamble on a satellite start-up pay off?

OneWeb satellite launch (Credit: Geopix / Alamy Stock Photo)

6 min read

Boris Johnson bought a cash-strapped satellite start-up in the middle of the Covid pandemic but it will take Brexit scars to heal for his bet to come good, Francis Elliott reports

Rishi Sunak was never keen on bidding £400m for a cash-strapped satellite start-up in a New York auction but Boris Johnson, egged on by Dominic Cummings, browbeat his chancellor into making the winning offer.

For Cummings, the purchase of OneWeb symbolised Brexit freedom – a newly nimble state making smart bets in a rapidly changing world to harness emerging technologies.

For Sunak, backed by officials in the Treasury and BEIS, it was a crazy-risky bet on an untested concept at an uncertain time (June 2020, just months into the pandemic).

The letter seeking a ministerial direction for the acquisition from a senior civil servant is a classic of the genre. Buying a failed start-up was “unusual for a government” it observed drily and was a “standalone high-risk investment with a possibility that the entirety of the investment is lost and no wider benefits accrued”.

The Treasury still regards the asset as ‘something of an embarrassment’ according to one former minister

Some three and a half years later, the taxpayer is currently sitting on a paper loss but the argument over who was right is far from over. All sides agree that OneWeb has enormous potential. By now, most people have heard of market leader in satellite-delivered communications Starlink, Elon Musk’s constellation. Amazon is also doing its best to catch up, with its Kuiper project launching its first prototypes last year. The injection of cash from the United Kingdom government and Indian telecoms magnate Sunil Bharti Mittal allowed OneWeb to cement its claim to the spectrum that – like Starlink and Kuiper – allows the satellites to operate in Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

But it needed what was in effect a merger with French firm Eutelstat to complete the first phase of the constellation of 634 small satellites 1200 kms above the earth. And it will need still more cash – one insider suggested £6bn – to complete its second stage and go head-to-head with Musk.

While the current share price of Eutelstat would suggest that the UK stake is currently worth around half what the taxpayer paid for it, ministers continue to be bullish about the asset pointing out that the UK has retained a so-called ‘golden share’.

According to the government’s own documents, this share requires the firm to prioritise the UK for manufacture and launch and gives the government rights to use the constellation for unspecified purposes but which include those of national security.

The utility and future of this share is open to question, however. One senior figure, who was closely involved in discussions about the initial purchase, says it did little to nothing to foster the UK’s own manufacturing base despite the UK’s acknowledged excellence in small satellite research and production.

As for national security, the mainstay of the UK’s sovereign space capability is the Ministry of Defence’s Skynet programme, now on its fifth generation of satellites. These relative giants do the heavy lifting of the UK’s military and intelligence communications and surveillance.

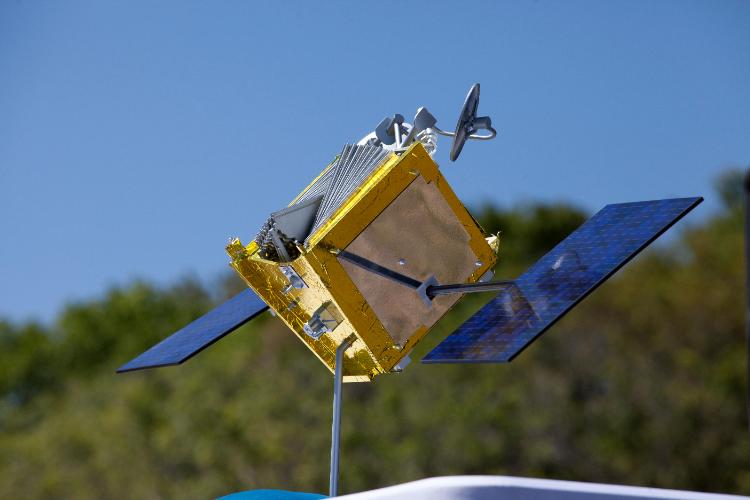

Model of a OneWeb satellite (Credit: NASA Photo / Alamy Stock Photo)

Model of a OneWeb satellite (Credit: NASA Photo / Alamy Stock Photo)

That’s not to say that OneWeb isn’t of interest to the MoD. “We’ve seen with Starlink and Ukraine how important these systems can be for battlefield communications. We’ve also seen the folly of allowing their use to be dictated by some weed-smoking dude in Nevada,” said an ex-military source, referring to Musk’s sometimes capricious attitude to allowing Kyiv’s use of his constellation. “You can be sure Nato would want something like OneWeb.” The United States military is sniffing around, too – it has shown enough interest for Eutelstat OneWeb to have set up an office in Virginia.

Then there’s the European Union – which is where OneWeb’s future gets really complicated. When it happened, the government’s purchase was written up in some of the more Brexit-enthusiastic press as a riposte to the decision by the European Commission to exclude the UK from the important parts of the EU Galileo programme, the satellite-driven project to ensure the bloc does not have to rely on the US Global Positioning System (GPS). The trouble is that OneWeb doesn’t currently offer the same capabilities as GPS. Some experts believe that it might be possible to use LEO constellations to do the job – and the option is included in a recent paper by the Space Based Positioning, Navigation and Timing Programme, which is what remains of the UK’s attempts to go-it-alone after the Galileo snub.

If it can be done it would add considerable resilience to systems on which so much of modern life depends, one of the reasons why the US was keen to see a UK sale say insiders. Another benefit of the OneWeb constellation is that it provides much denser coverage for polar regions than traditional so-called geostationary (GEO) satellites, which favour the equatorial regions they orbit. That is attractive to those that fear the poles may become geopolitical flashpoints in a warming world.

The EU, meanwhile, might have Galileo but it doesn’t have its own LEO broadband constellation and it wants one. Given its French co-owners, one might have thought that Eutelstat OneWeb was well placed to hoover up large parts of the $6bn contract and massively expand its constellation to really rival Musk and Jeff Bezos.

The UK’s ‘golden share’, however, remains a significant problem. Thierry Breton, the EU Commissioner for the single market, has made clear his reluctance to sanction any use of an asset over which the bloc doesn’t have complete sovereign control.

As the Brexit scars heal, the grand bargain that allows the EU access to OneWeb in return for UK access to Galileo may be struck after all. Sir Keir Starmer has himself signalled the possibility of a defence and security pact that was always supposed to be the companion to the trading deal with the EU.

The danger is that the project remains in limbo until those stars align. There are signs the UK is prepared to compromise. Insiders say the government isn’t going to demand that all manufacturing of second generation OneWeb satellites is conducted solely in this country. They say only that it wants to ensure that UK firms already part of the international satellite supply chain ecology are given a fair chance to compete.

There remains an ambiguity in government about its “highly unusual” acquisition. The Treasury still regards the asset as “something of an embarrassment”, according to one former minister. Yet Jeremy Hunt allocated £121m for space in the autumn statement, including £15m specifically for LEO research.

At the very least the UK has bought itself a place at the table – whether it has the pockets or the nerve to stay in the game remains to be seen.