The Professor Will See You Now: Roughs and Riots

4 min read

In an occasional series, Professor Philip Cowley offers a political science lesson for The House’s readers. This week: roughs and riots

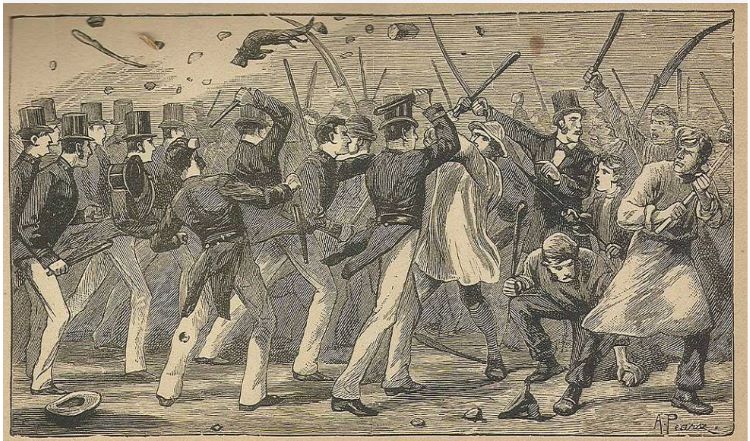

We would be worried about the probity of any general election that witnessed 39 riots and a further 300 or so further violent incidents, resulting in 17 deaths. Yet that was the score card for the general election of 1868 – and just in England and Wales.

It wasn’t a one-off. The two elections following the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872 between them saw a further 61 riots and 400 or so other violent incidents. Plus another 13 deaths.

There is pretty clear evidence that much of it was co-ordinated by politicians

As late as 1885 there were 27 riots, over 360 incidents, and five deaths. These, in the words of the Saturday Review, included “deliberate attempts to murder unpopular candidates”. The Times described that election as “on the whole pure”, which makes you wonder what the impure ones looked like.

These stats are all taken from a fascinating new article, just published in Past and Present, which comprehensively demonstrates that previous historians have hugely underestimated the scale of the violence involved in Victorian elections. The process of democratisation after 1832 was not as placid as it is often claimed. Indeed, rather than declining as the 19th century wore on, there was a particularly sharp increase in the levels of electoral violence between the second and third Reform Acts.

There were some regional variations (East Anglia and the East Midlands seem to have been particularly violent places to stand for Parliament) – although it was pretty common everywhere. In the 50 or so years between 1832 and 1880, over 90 per cent of constituencies saw some electoral violence. Violence, the authors conclude, was “endemic” in 19th-century elections.

Nor was this just spontaneous bottom-up rowdiness. There is pretty clear evidence that much of it was co-ordinated by politicians, who used it as a campaigning tool. Violence was more commonly found in marginal seats and often involved “roughs” (the phrase used at the time) who would be hired to break up rival meetings or intimidate voters.

The authors note that even full-on riots, involving military interventions and deaths, were often not front-page news and could be found be tucked away on the inside pages. This is both a commentary on their unexceptional nature but also perhaps excuses the inability of previous historians to identify them.

This research was only possible because of the mass digitisation of newspaper archives – which remain a criminally underused resource by both historians and political scientists. Using machine learning, but checked by a team of research assistants, the authors searched for examples of electoral violence in over 1.3 million articles in the British Newspaper Archive, covering more than 1,000 local and national papers.  Despite excluding Scotland (on grounds of cost) and Ireland (where levels of violence were already known to be relatively high), this still involved a corpus of some two billion words. It is research that would simply not have been possible without digitisation.

Despite excluding Scotland (on grounds of cost) and Ireland (where levels of violence were already known to be relatively high), this still involved a corpus of some two billion words. It is research that would simply not have been possible without digitisation.

The project has produced an accompanying interactive map online – which allows you to examine each incident. In Lancashire alone, for example, there were 26 election riots between 1832 and 1910.

As always, no doubt a different coding scheme would come up with different figures. One man’s riot might be another’s violent disturbance – although in many cases these did involve the reading of the Riot Act, so there’s not really much to debate, and it’s difficult to argue a lot with the number of deaths. Slice it how you like, the sheer scale of violent incidents is so great that the overall conclusion seems unanswerable.

Your further reading for this week: L Blaxill et al, Electoral Violence in England and Wales, 1832-1914, Past and Present (2024)