Starmer’s honeymoon in office was short-lived – but how does it compare to past PMs?

Keir Starmer hosts a meeting of Indian investors and CEOs inside No 10, December 2024. (Credit: Henry Nicholls/Pool Photo via AP)

13 min read

Having won a historic landslide general election victory in July, it is fair to say that Labour’s honeymoon in office has been short-lived.

Ipsos polling shows that 53 per cent of the public are disappointed by what the party has done in office so far. Net favourability towards the Labour Party has fallen from +6 in July to -21 in December. When asked to give Labour a score out of 10 for its record in government, the public gives them a four. Reasons given include talk of broken promises, a gloomy economic outlook and a negative response to policies such as the means-testing of winter fuel payments or rows about political freebies from donors.

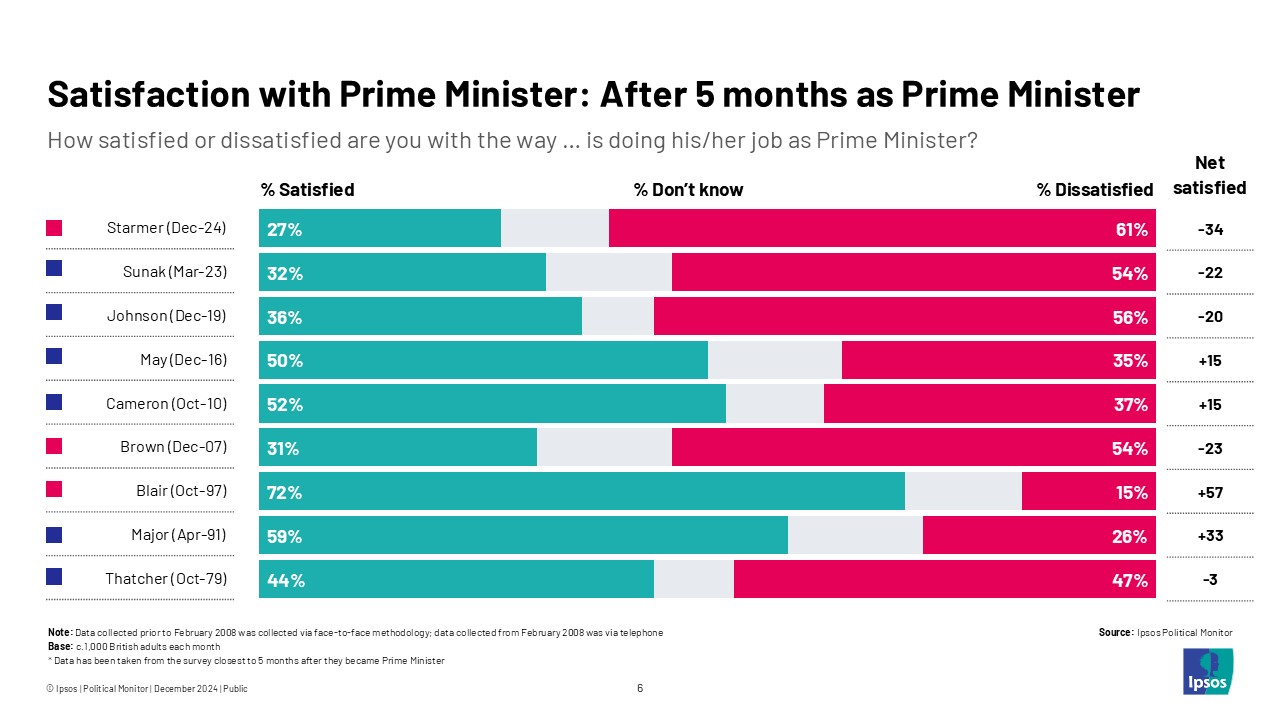

No surprise, then, that net satisfaction with Keir Starmer’s performance as Prime Minister is in deeply negative territory. With 27 per cent of the public satisfied and 61 per cent dissatisfied, Starmer’s score of -34 is the weakest Ipsos has ever recorded for a Prime Minister after five months in office – with records going back to 1979 and Margaret Thatcher. Though, of course, Liz Truss did not even make five months.

But what does this tell us about Labour and Starmer’s longer-term prospects? In this article, we delve into the Ipsos archives to look at how Starmer’s ratings as Prime Minister today compare to other prime ministers at different moments in office. The purpose: to contextualise Starmer’s current position and understand how he might turn things around.

The Prime Ministers who never won (Sunak and Brown)

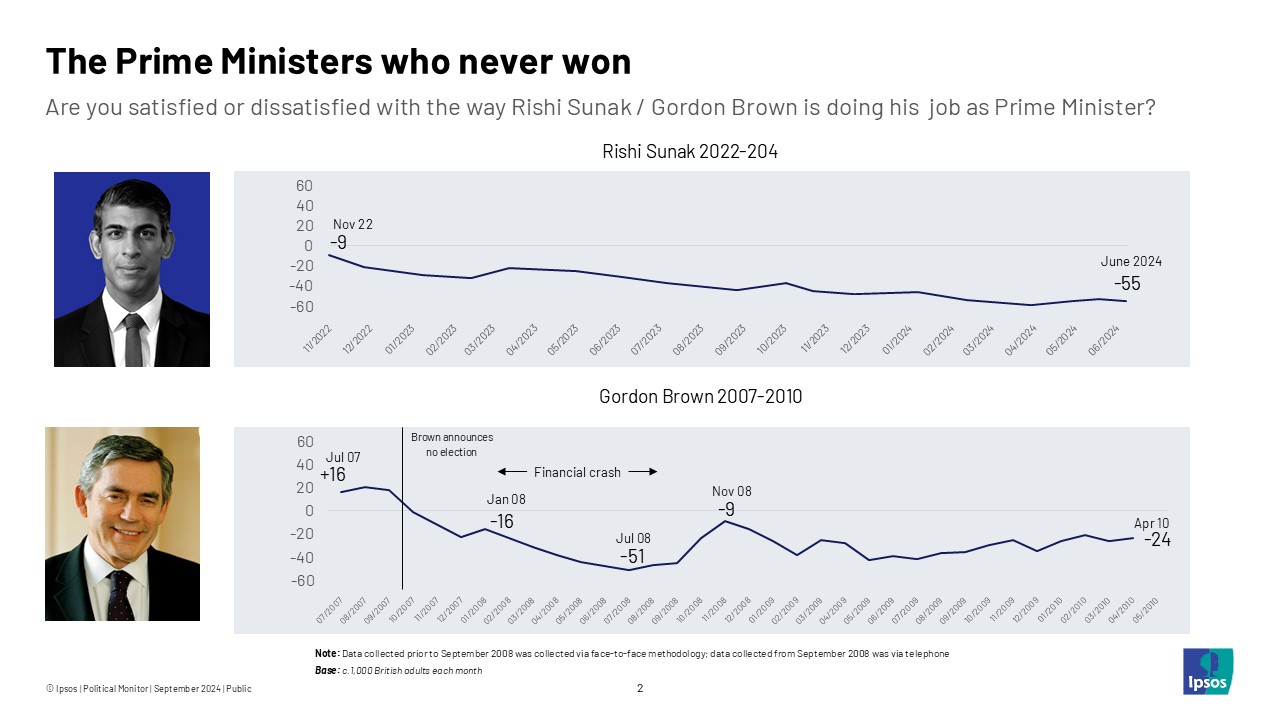

Two prime ministers Starmer will not want to emulate are Rishi Sunak and Gordon Brown. Rishi Sunak took office in late 2022 with a net rating of -9 and the story of his premiership was one of steady decline from an already weak base. Unable to assert control over the political narrative, amidst the legacy of 'partygate', a cost of living crisis and a strong public desire for change, he left office defeated with a rating of -55.

Gordon Brown was slightly different. His net rating did improve from the -51 registered at his nadir in the summer of 2008 (at the height of the financial crisis) to -24 at the 2010 general election. Yet some exceptions aside, his personal ratings were consistently in deeply negative territory. He was never able to recover the positive ratings he appeared to have before announcing there would be no snap election in the autumn of 2007.

Of course, aside from demonstrating the danger of not being able to properly seize the political agenda once it has turned against you, it can be argued that Sunak and Brown are not suitable comparisons for Starmer. Both took over after their parties had been in office for some time and neither won an election to get there. Perhaps the best comparators are those who won from opposition.

You only win once (Major, May and Johnson)

Before we get there, the cases of John Major, Theresa May and Boris Johnson all offer lessons for Starmer and Labour too – even if they did not win from opposition.

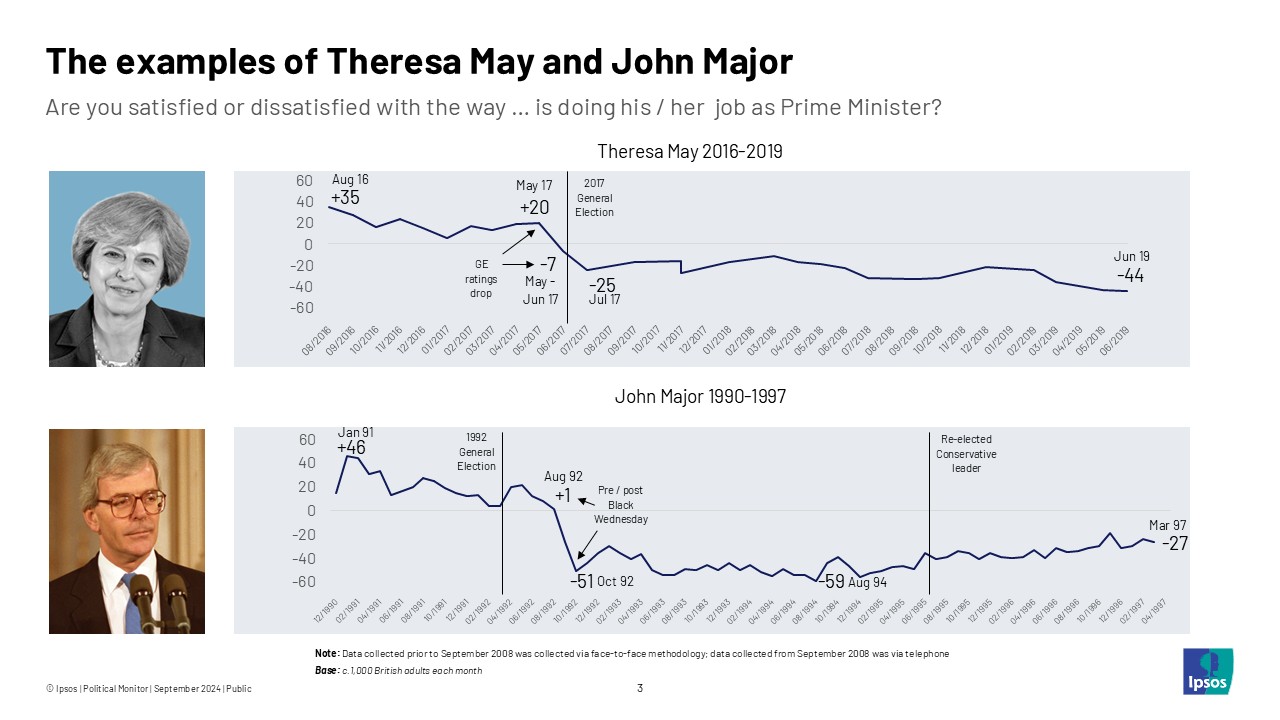

Major and May had more lasting political honeymoons than Starmer. Both enjoyed strong net positive ratings initially before winning a general election – in the case of Theresa May only just – with ratings much stronger than Starmer has today. But Major and May also offer a cautionary tale of how political crises can turn public opinion against prime ministers – even when starting from a higher base.

For Major, Black Wednesday was the catalyst for his ratings sharply falling from +1 in August 1992 to -51 in October. Whilst his ratings recovered somewhat by the time of the 1997 election to -27, they were never what they were. For Theresa May, her political crisis was the 2017 election campaign itself. She enjoyed ratings of +20 in May 2017, just after she called it, only to register -7 shortly before polling day.

Opposition matters

Of course, Major and May experienced very different outcomes at the elections they fought. Major lost in a landslide to Tony Blair, whereas May – though wounded politically – remained in office. Here we must consider the opposition. Major was up against Blair, who fought the 1997 election with a net satisfaction rating of +21. May faced Jeremy Corbyn who, whilst having a good campaign in 2017, finished that election on -11.

It would be too simplistic to argue general elections are won and lost on leader ratings alone, but these examples are reminders of how voter choices are relative. Unpopular governments and prime ministers can win – if they are more popular than the alternative. Which may be of some comfort to Labour today.

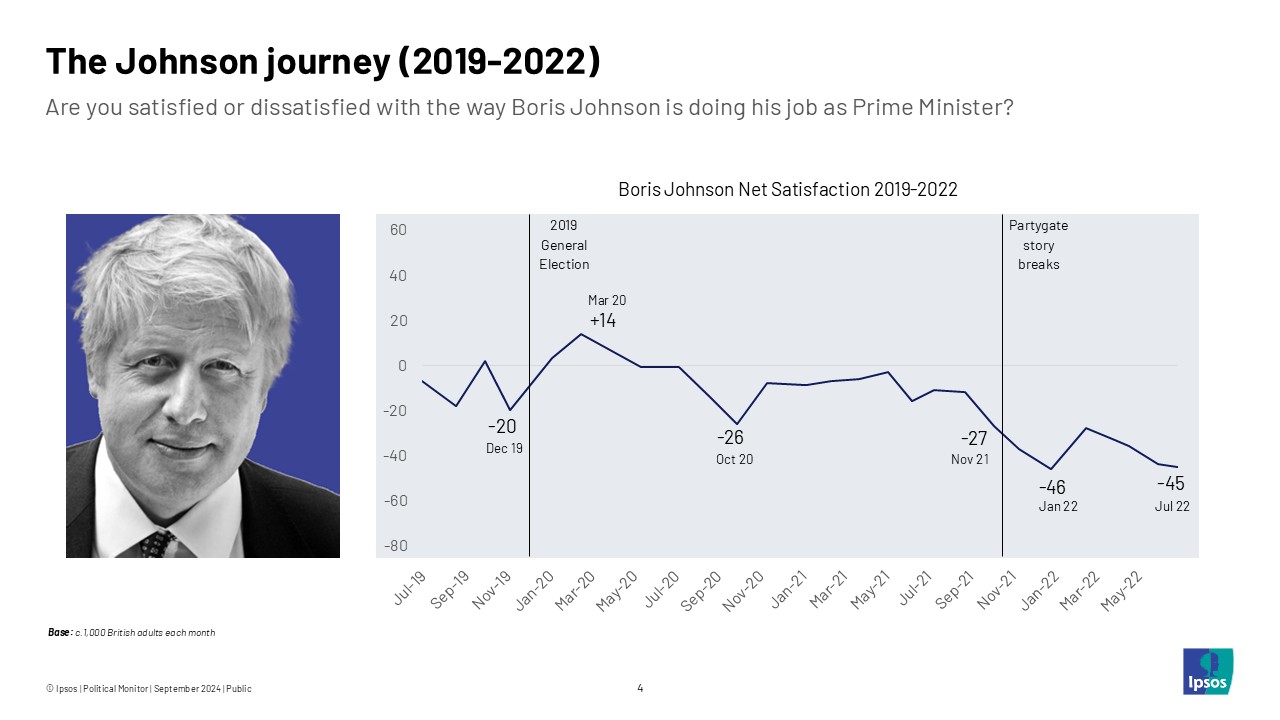

What of a more recent example? Boris Johnson took over from Theresa May in 2019 and won a general election that year in convincing fashion. His time in office was certainly politically turbulent, with Brexit struggles, Covid, Ukraine and a cost of living crisis in a short period of time. However, many of the lessons we learn above we learn again here.

Johnson was able to win a general election with relatively weak leader satisfaction ratings (-20) as he faced an opponent in Jeremy Corbyn who was even more unpopular (-44). His ability to articulate a message in ‘Get Brexit done’ that resonated with his target voters was also critical.

However, like Major and May before him, Johson also experienced a defining crisis in Partygate which saw his ratings sharply drop, from -27 beforehand to -46 in January 2022. His ratings recovered a bit that spring but as the scandal rumbled on, his political authority drained away until he was replaced by Liz Truss.

We are starting to see some patterns emerge here. But what can we learn from the prime ministers who Starmer will presumably want to emulate – those who won and won again?

The Prime Ministers who won from opposition – and won again

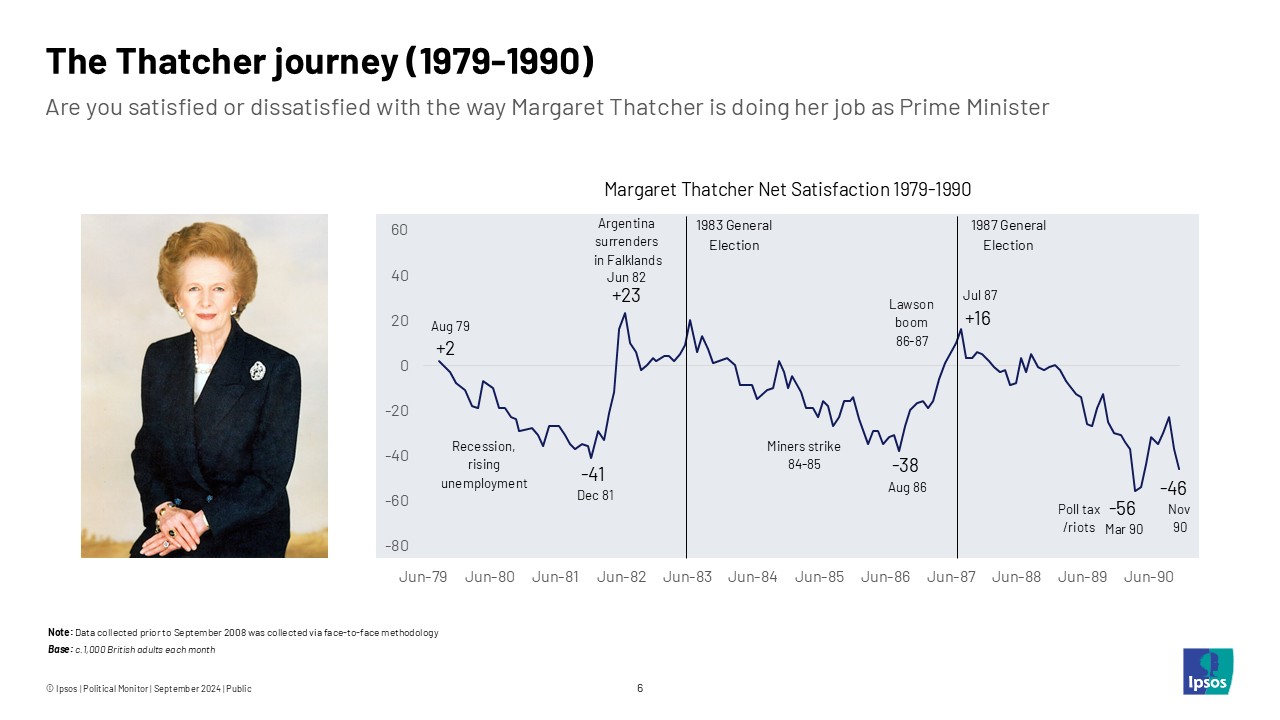

Margaret Thatcher

Given her length of time in office, it is perhaps unsurprising that Thatcher’s personal poll ratings ebbed and flowed. But it is easy to forget how poorly she started. Her net rating fell from net positive just after winning the 1979 election to -41 in December 1981 – similar to Starmer today – amidst a recession and rising unemployment. After winning in 1983, her ratings also fell to -38 in August 1986 in the aftermath of the miners’ strike and continuing unemployment despite a growing economy.

Yet, unlike other prime ministers we have discussed so far, Thatcher was able to recover her personal poll ratings, comfortably winning both the 1983 and 1987 general elections. (Though even she was politically mortal, being replaced by John Major in the aftermath of the poll tax riots at the turn of the decade.)

How did Thatcher turn things around twice? Her handling of the Falklands war was clearly a driving factor in her ratings surging to +23 in June 1982. The ‘Lawson economic boom’ of 1986 was also a factor in turning around her flagging ratings during the middle of the decade.

Meanwhile, the presence of the Lib Dem/SDP ‘Alliance’ was important in both the 1983 and 1987 general elections, wiht the combined vote share of the Alliance and Labour on both occasions exceeding the Conservatives by more than 10 points. We will not dissect the cause-effect here but it was clearly part of the tale, along with Thatcher’s handling of certain crises and ability to demonstrate delivery to voters at key moments.

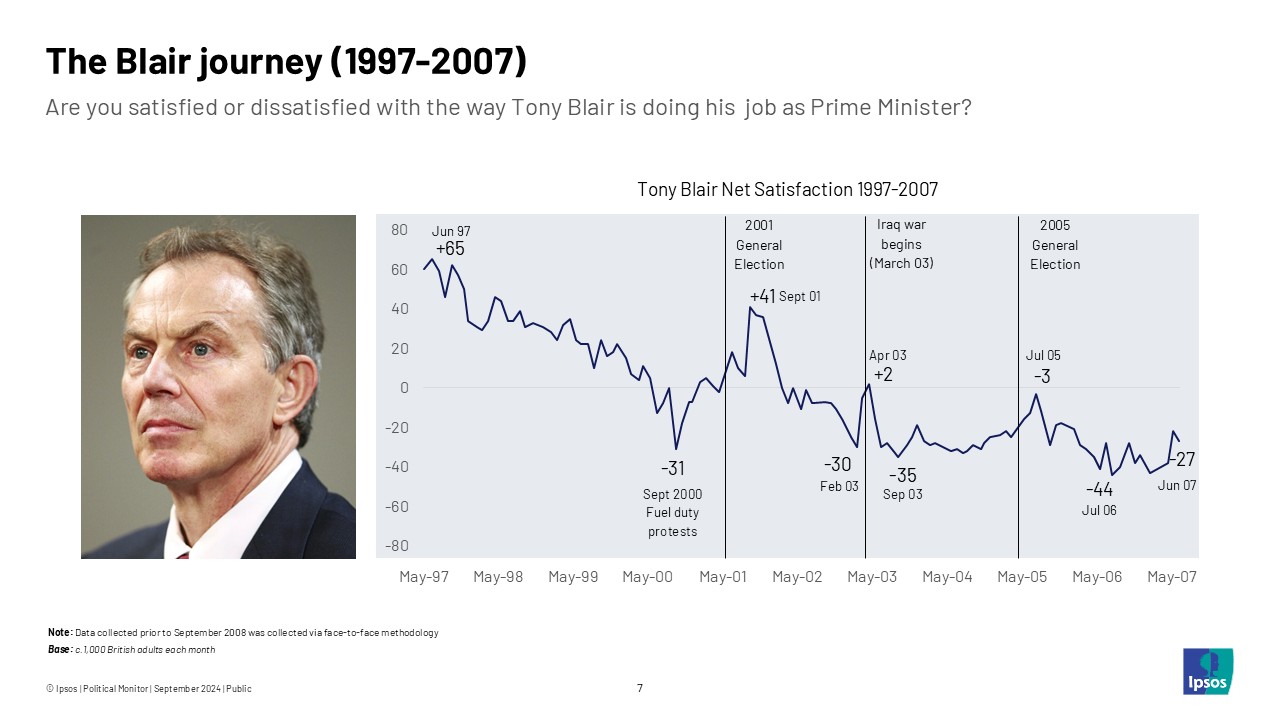

Tony Blair

Labour has its own prime minister who won three elections. Blair entered office with personal poll ratings pretty much unheard of before or since, but these would fall during his first term. However, Blair’s low point of -31 during the fuel duty protests in 2000, only slightly ahead of where Starmer is today, proved a short-lived one. Blair won a second landslide in 2001 with a net rating of -2 (compared to William Hague’s -29). Economic optimism with Ipsos stood at -4 (compared to -49 today). Labour’s message of "a lot done, a lot left to do" appeared to resonate.

Blair’s second term would see his net satisfaction rating increase to +41 at the time of the September 11 attacks in 2001 but it would be the Iraq war that would have a longer effect. Blair hit a low of -35 in September 2003 and had the rare distinction in Ipsos history of being the only prime minister to win re-election with a net satisfaction rating worse than the leader of the opposition (Blair on -25 in March 2005, Michael Howard -10).

Much is made of Blair winning a third term ‘despite Iraq’, but he was arguably politically fortunate that votes lost on that issue went to the Liberal Democrats rather than a Conservative Party that also supported the war. It is likely just as significant that Labour went into the 2005 general election more trusted on the economy than the Conservatives too (Labour 44 per cent, Conservatives 18 per cent, Ipsos April 2005).

In any case, despite rallying after the 2005 election, Blair’s ratings would fall to a low of -44 in July 2006, before he was replaced by Gordon Brown in the summer of 2007.

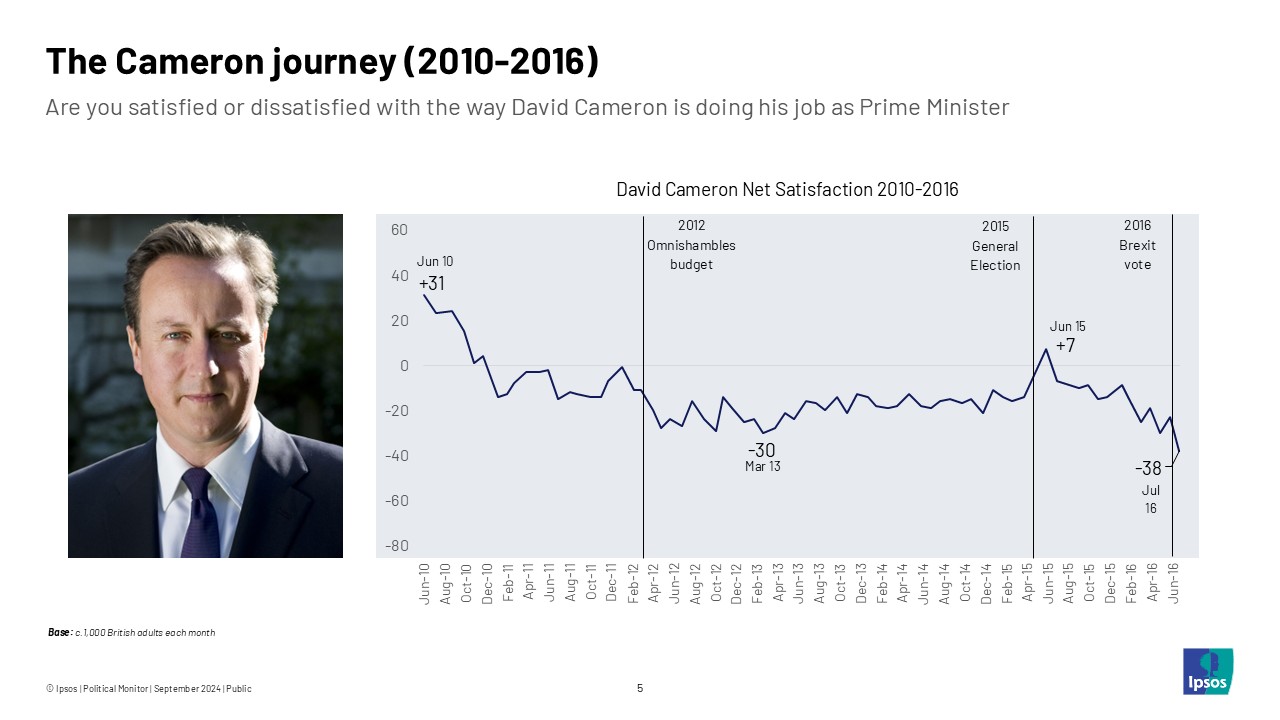

David Cameron

The final example on our list is David Cameron, who won the 2010 and 2015 general elections, only to resign shortly after the Brexit vote of June 2016.

Cameron’s ratings also started in strong net positive territory only to fall sharply, although his personal poll ratings in his first term after that were less volatile than other prime ministers. His net satisfaction rating fell to -30 in March 2013 but would steadily recover to reach -2 just before in the 2015 general election – the same rating as Blair in 2001.

Starmer will no doubt wish to replicate such a recovery, a notable aspect of which was a significant improvement in public economic optimism. When Cameron’s net rating as prime minister stood at -30 in March 2013, Ipsos’ net economic optimism index stood at -30 too. This meant that 18 per cent of the public expected the economy to get better in the following year and 48 per cent expected it to get worse. But by the time of the 2015 general election, net economic optimism stood at +26. Whilst the economic legacy of Cameron and George Osborne is hotly contested, their political message of a "long-term economic plan" clearly cut through in a positive way for them at the time.

Improved economic optimism and a recovery in Cameron’s personal poll ratings were coupled with significant public doubt about the Labour Party and its leader Ed Miliband. Cameron was consistently seen by the public as the more capable of being prime minister. Miliband registered net satisfaction ratings of -19 going into the 2015 election. Meanwhile, the Conservatives went into that election more trusted on the economy by an 18-point margin (Conservatives 41 per cent, Labour 23 per cent, Ipsos April 2015). This proves once again that politics is always relative.

Learning the right lessons

What does this all mean for Starmer and Labour today? In many ways they are in a strong position, with a large majority in Parliament and time on their side. In other ways they are in a weak one, with public opinion shifting quickly against them. The speed at which Johnson’s winning 2019 voter coalition fell apart offers a cautionary tale.

1. Labour has time – but needs to show delivery driven by purpose. ‘Delivery’ means meaningful progress on public priorities like the economy, immigration and fixing public services. ‘Purpose’ means telling the right political story whilst doing so – avoiding the ‘Biden trap’ of having a laundry list of apparent achievements but no overarching message that connects with the public, aligns with their lived experiences and aspirations, and can rebut opposition attacks.

There are several examples of this working above, but one that stands out is Cameron in 2015. His Conservative Party managed to turn mid-term pessimism around and enter the election with a winning message and improving economic optimism. Starmer and Labour will hope for similar. Consistency is key; reinforcing a winning message time and time again, backed up by achievements the public can see.

2. Politics is relative – defining your political opponents is key to success. A common theme above is that relatively unpopular governments can win if they are more popular than the principal opposition. Labour is still more trusted on the economy than the Conservatives and Starmer the preferred prime minister to Kemi Badenoch, who is still a relatively unknown. This will all offer some comfort to Labour today. Yet their longer-term prospects will partly rely on whether they can frame the Labour–Conservative choice in a politically advantageous way in the future too.

3. The wider political environment matters. At the time of writing, Reform UK looks like it is here to stay, winning votes that might otherwise go to the Conservatives. Perhaps Reform UK will be this generation’s version of the Alliance in the 1980s, only this time helping Labour by suppressing the potential Conservative vote. The wider political environment could hurt Labour, however, as Reform UK could also take support from the governing party (for example in Wales and other parts on the UK). And an SNP recovery in Scotland would see Labour lose seats next time.

4. Crisis will offer maximum political danger – but also opportunity. We have seen several examples above, from Black Wednesday to partygate, where prime ministers have been irreversibly damaged by events. But we have also seen examples such as the Falklands War where they can be the making of a prime minister’s reputation. How Starmer and his government handle the unknown crises to come will likely shape its political destiny as much as anything else. Voters tend to reward leaders they see as strong and decisive. Starmer will hope to have the chance to demonstrate he is both.

It is still far too early to really know which direction Starmer and his Labour government will take. Despite early setbacks, they still have a lot going for them, including a large majority in Parliament, a relatively weak opposition, and time.

In many ways, history shows that prime ministers rely on a good deal of luck. The right crisis comes along at the right time, the global economy improves or the domestic political environment is favourable.

However, more often than not, prime ministers make their own luck. By doing the hard yards delivering on public priorities, successfully defining their political and governing philosophy in a way that resonates with the public (and helps define their opponents in a less favourable light) or rising to the big moments of a given parliament. Thatcher, Blair and Cameron were all able to do so in different ways, enabling them to win and win again. Starmer and Labour will hope they can yet do the same.

Keiran Pedley is director of politics at Ipsos