A tale of two parties: the origin of the Tory Party

King Charles II (Credit: Steve Vidler / Alamy Stock Photo)

8 min read

Lord Lexden details the origin of the Tory Party – born of a crisis triggered by a lying priest and a monarch’s ruthless suppression of the Whigs

The first Whigs appeared on the political scene just over 340 years ago, to be followed swiftly by implacable Tory foes, amidst quite extraordinary events towards the end of the reign of that merry monarch, King Charles II.

Until it actually happened in 1678, no one could have imagined that the entire political world would be convulsed by a pack of lies, devised almost entirely by one man, Titus Oates, a homosexual former Anglican priest who had been unfrocked and sacked as a naval chaplain because of his unsurprising improprieties (which did not stop him denouncing others for sodomy). He then converted to Catholicism and started training as a Jesuit priest, but failed his Latin exam which put paid to his hopes of a second clerical career.

“Dr” Titus Oates (he loved parading a non-existent Catholic divinity doctorate) is undoubtedly one of the greatest and most repellent scoundrels in British history. Though only 29 when he began naming various fellow Catholics as traitors, he was richly endowed with the indestructible self-confidence that all successful liars must possess. He denounced everyone who dared dispute his amazing claims.

Titus Oates… is undoubtedly one of the most repellent scoundrels in British history

Jesuit priests and Catholic members of the nobility had, Oates insisted, united to form a terrifying conspiracy against Britain’s proudly Protestant state. London would be burnt down and its inhabitants massacred; a Catholic French army would invade and the king would be assassinated. This fantastic, imaginary threat to the state is known in history as the “Popish Plot”. “All England broke into unreasoning panic”, one nervous observer said.

For two and a half years, from September 1678 to March 1681, no one was safe. Men in public life went in fear of sudden arrest, imprisonment and execution. At least 22 innocent people, including a number of respected and learned Jesuit priests, were executed because of Oates’ lies.

“The unreasoning panic” engulfed Parliament, with which Charles II had acute difficulty throughout his reign. His wise hand could not restrain its members now. In October 1678 the Commons declared that “there hath been and still is a damnable and hellish plot contrived and carried out by the popish recusants for assigning and murdering the King”, even though the king himself did not believe it.

King Charles II (Credit: IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo)

King Charles II (Credit: IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo)

The turmoil was a gift to the most accomplished and versatile politician of his day, Anthony Ashley Cooper, first Earl of Shaftesbury. He was notorious in his time as the prince of opportunists, sometimes serving governments and sometimes opposing them, as suited his interests – a kind of highly talented Vicar of Bray turned politician.

He became for a time the man around whom events chiefly revolved. What was essentially a struggle for power took place between Shaftesbury and his allies on the one side, and the king on the other. The monarch dissolved Parliament three times between January 1679 and January 1681, in the hope of securing through fresh elections (which involved some 2.6 per cent of the population) a majority of MPs who would not try to impose on him a fundamental constitutional change to which he was totally opposed.

That change was the exclusion of the king’s Catholic brother – James, Duke of York – from the line of succession to ensure that another Protestant monarch followed Charles II. Exclusion was the key demand of those who were exploiting the Popish Plot for political advantage. Shaftesbury was its most prominent and effective proponent.

The three “Exclusion Parliaments”, as they came to be known, gave strong support to the policy with which Shaftesbury was firmly identified. Much credit has been given to him for assembling the first Whigs, seen by historians as the earliest recognisable British political party, during the years 1679-81. The prospect of another civil war to resolve fundamental differences, which worried so many people, disappeared.

The first Whigs did not achieve a high degree of internal self-discipline or work out a collection of coherent policies to help carry them forward in this first phase of their existence. It would perhaps have been rather surprising if they had done so in their earliest days. But they campaigned vigorously through petitions and addresses to Parliament, through press propaganda and urban political clubs.

Charles II defeated these Whigs with their intolerable demands. In March 1681 he sent the third Exclusion Parliament packing; even though it was held in Oxford, away from the radical London mob which intimidated Westminster, it proved no less truculent than its predecessors. The dissolution was widely applauded by public opinion, which had grown tired of acute parliamentary strife and had at last turned against Titus Oates.

Parliament would never meet again under the merry monarch. In the last four years of his reign, Charles II carried out a ferocious purge of his Whig opponents, turning them out of office at national, county and municipal level. The king’s loyal supporters, who replaced them in every part of the country, were naturally reviled by the victims of this royal campaign.

The Whig losers cast around in the extensive lexicon of colourful contemporary abuse. In the course of 1681 those who approved of what the king had done got used to being called Tories. It was meant to be intensely insulting.

Those on the receiving end were being likened to lawless Irish brigands, whose random violence in their own country was very familiar to Englishmen of the time. A tract published in 1683 referred in horrified terms to Irish Tories as “popishly affected, outlaws, robbers, such as our law saith have Caput Lupinum, fit and ready to be destroyed and knocked on the head by any one that could meet with them”.

“The Tory slogan ‘Church and King’ defined their purpose as bastions of Anglicanism and monarchy”

Those who were thus mocked showed their indifference to such insult and scorn by adopting the very rude term as their official name. In this, they followed the example set by their opponents. Whigs or Whiggamaires (an earlier variant) were, it seems, originally Scottish horse thieves. By the 1640s, the unappealing term was being used to describe bands of fearsome armed rebels who roamed lowland Scotland. When this awful word was applied to them, Lord Shaftesbury and his friends responded by stitching the term proudly on their banners.

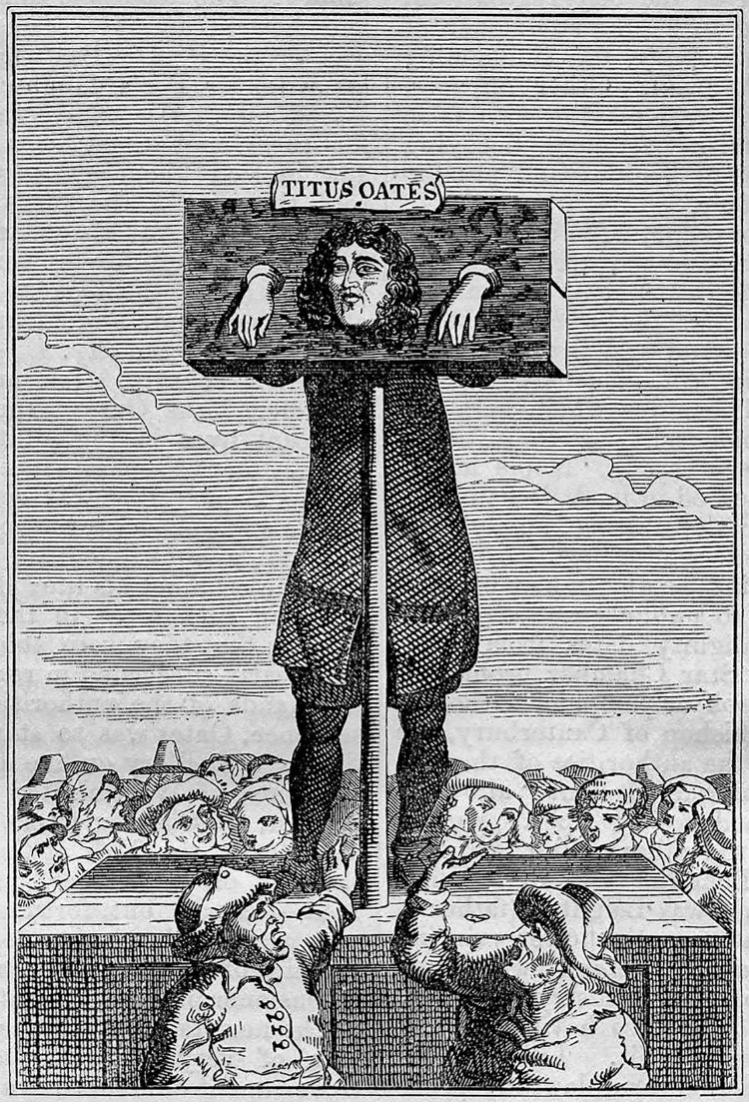

Titus Oates (Credit: Niday Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo)

Titus Oates (Credit: Niday Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo)

The two names, and the sharp party divisions they signified, passed quickly into everyday use in the course of 1681. By October that year news of them had reached Derbyshire. A contemporary recorded the following conversation: “Ms. H. of Chesterfield told me a gentleman was at their house and had a red Ribband in his hat, she askt. him what it meant, he said it signifyed that he was a Tory, whats that sd she, he ans. an Irish Rebel, – oh dreadful that any in England dare espouse that interest. I hear further since that this is the distinction they make instead of Cavalier and Roundhead, now they are called Torys and Wiggs, the former wearing a red Ribband, and the other a violet… and the Torys will Hector down and abuse those they have named Wigs.”

Charles II has the clearest claim to the credit for the rapid and unexpected emergence of the Tory Party in 1681. His supporters were thrust together with a much greater sense of common identity as the beneficiaries of the royal campaign against the Whigs.

The Tory slogan “Church and King” defined their purpose as bastions of Anglicanism and monarchy. No one felt the need to go further and develop a political programme or establish a national organisation. Here again the Tories emulated the Whigs.

When elections resumed in 1685 (under the disastrous King James II) Tory MPs romped home: some 470 of them sat opposite a derisory 57 Whigs. The victors found government ministers in office at Westminster who now called themselves Tories too, and so readily gave them, and the monarch, loyal support.

The cunning Shaftesbury was dead, his name and his work disgraced. The Whigs were only rescued from near oblivion, and Britain from the prospect of a one-party state under firm royal control, by James II’s gross mistakes which cost him the Crown in 1688.

Titus Oates had set out 10 years earlier to create political mayhem through his bogus Popish Plot. For two and a half years he was a powerful malign force in the land. Then stability returned, thanks to a determined monarch whose resolution ended Oates’ crisis, and brought the Tories into existence in the course of his ruthless suppression of the Whigs.

But would there ever have been a Whig Party – or a Tory Party – without Oates, that lying scoundrel?