Tory support among Chinese and Hindu voters presents opportunity and risk for Kemi Badenoch

6 min read

The Tory performance with British Hindu and British Chinese voters on 4 July was one of the very few bright spots for the party. But our analysis suggests that a strategy of going after Reform voters could cost the Conservatives support with these groups.

One of the few bright spots for the Conservatives in the 2024 General Election was their strong showing among British Hindu and British Chinese voters. Although support for the Conservatives was down amongst almost every demographic group, the party still managed to win the support of one in five British-Chinese voters and a third of British Hindus. Although these figures may not seem particularly impressive, they occurred in the context of winning the support of only 14 per cent of all other ethnic minority voters.

In the 2019 election, the Conservatives' sweeping victory relied on a coalition that included working-class white voters and highly educated British Chinese and British Hindu voters. To reconstruct a winning electoral coalition, the Conservatives need to know which issues their potential supporters are divided on.

From June to September 2023, Focaldata surveyed 6,384 white respondents and 4,780 ethnic minority respondents, including 555 British Hindu and British-Chinese respondents. A colleague and I at the UK in a Changing Europe and Focaldata have used this data to analyse the myth and reality of increasing support for the Conservatives among ethnic minorities.

Education levels have increasingly shaped people’s views on economic and cultural issues, often creating sharp divides. Yet, despite this education gap, our research shows that British Chinese and British Hindu voters share remarkably similar views to white school leavers on these issues. Immigration, however, stands out as a potentially divisive topic. Pro-immigration attitudes are much stronger among degree-holding British Hindus and British Chinese compared to non-university-educated white voters.

In other countries, centre-right parties have also successfully appealed to ethnic minorities. In Canada, for instance, under former leader Stephen Harper, the Conservative Party broke the Liberals’ stronghold over the ethnic minority vote by effectively making the case that their values — faith, social conservatism, and entrepreneurship — aligned more closely with the Conservatives than other parties. In the US, the Republicans have long argued that the religiosity of Hispanic voters makes them ‘natural conservatives’. Although a perception of the party as xenophobic long held it back from making inroads with the community, in the 2024 Presidential election, 55 percent of Hispanic men voted for Donald Trump.

In the UK, the Conservatives significantly increased their support among minority voters starting in 2015, winning just under half of the Hindu vote and a third of the Chinese vote. Given the historical tendency of the overwhelming majority of ethnic minorities to support Labour, this represented an important development.

The growing strength of the Conservatives amongst British Hindu and Chinese voters is even more surprising given that this group is among the most educated in the electorate. 61 per cent have a university degree or professional qualification, compared to 40 per cent for the rest of the electorate. Cross-national data shows university graduates are considerably more likely to vote for parties on the left and have substantially more left-wing values on cultural and economic issues than school leavers.

Indeed, white university graduates in the UK are substantially more likely to vote for parties on the left. Yet, British Chinese and Hindu voters with a degree are 22 percentage points more likely to vote for the Conservatives than white voters with a degree, and 16 per cent points more likely to vote Conservative than their co-ethnics/co-religionists voters without a degree.

.png) UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

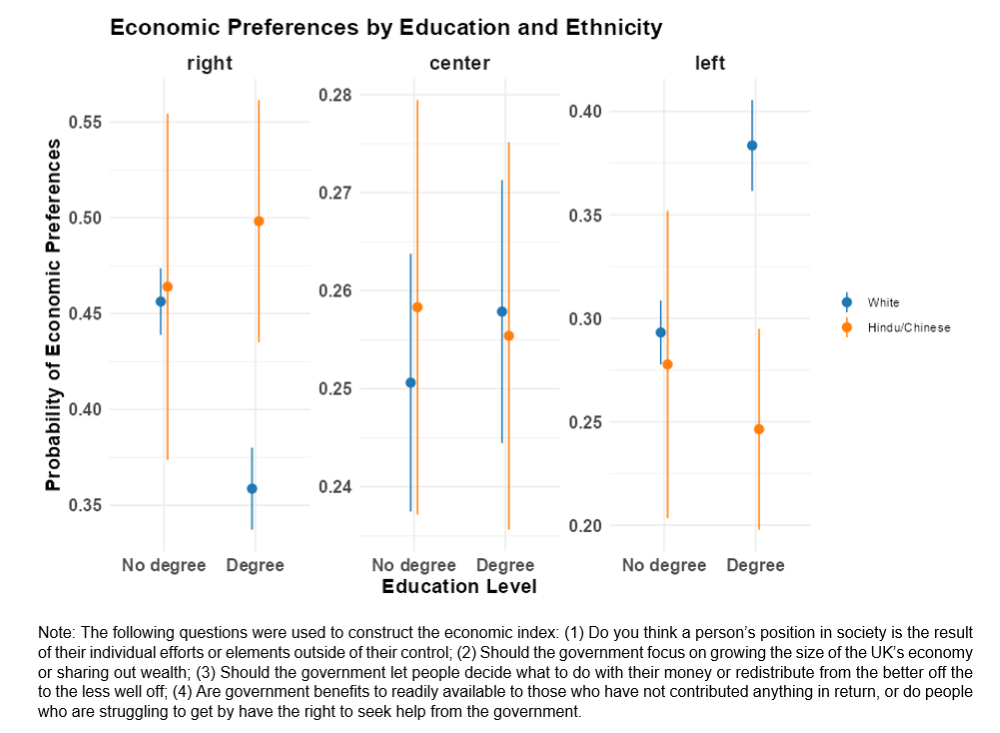

This raises the question, are university-educated Hindus and Chinese more right-wing in their social values and economic preferences than white graduates, as well as their peers without a degree?

The data shows that British Hindu and Chinese degree holders are indeed more likely to have right-wing economic preferences than university-educated whites. When controlling for other factors, I find there is a 49 per cent chance that a Hindu or Chinese graduate voter will have right-wing economic preferences, compared to 36 per cent for white graduates.

Economic issues are unlikely to be a faultline for the Conservatives in recreating their electoral coalition of white school leavers and highly educated minorities, as both groups are almost equally likely to have right-wing economic preferences.

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

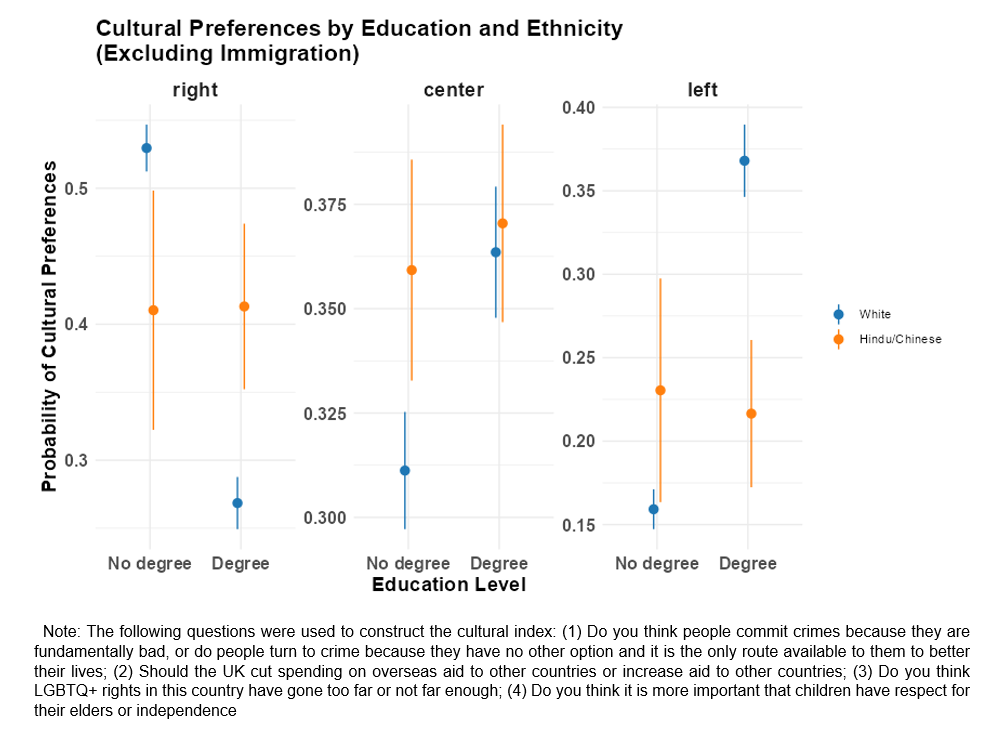

Looking at cultural issues (not including immigration), such as views on LGBTQ+ rights and societal versus individual responsibility for crime, Hindu and Chinese voters with a degree are much more likely to be socially conservative than their university-educated white counterparts. The former are 15 per cent more likely than the latter to have ‘authoritarian’ views on cultural issues. Again, there is not the same divide among Hindu and Chinese graduates and non-graduates as exists among white voters. Among this group of minority voters, there is no meaningful difference in the likelihood of holding conservative views on cultural issues between degree holders and those who did not attend university.

The differences in attitudes over cultural issues between non-degree-holding whites and university-educated British Hindus and British Chinese are more pronounced than they are over economic issues. However, these differences are unlikely to pose a strategic dilemma for the Conservatives. These two groups are among the most likely in the electorate to hold right-wing attitudes on cultural issues.

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

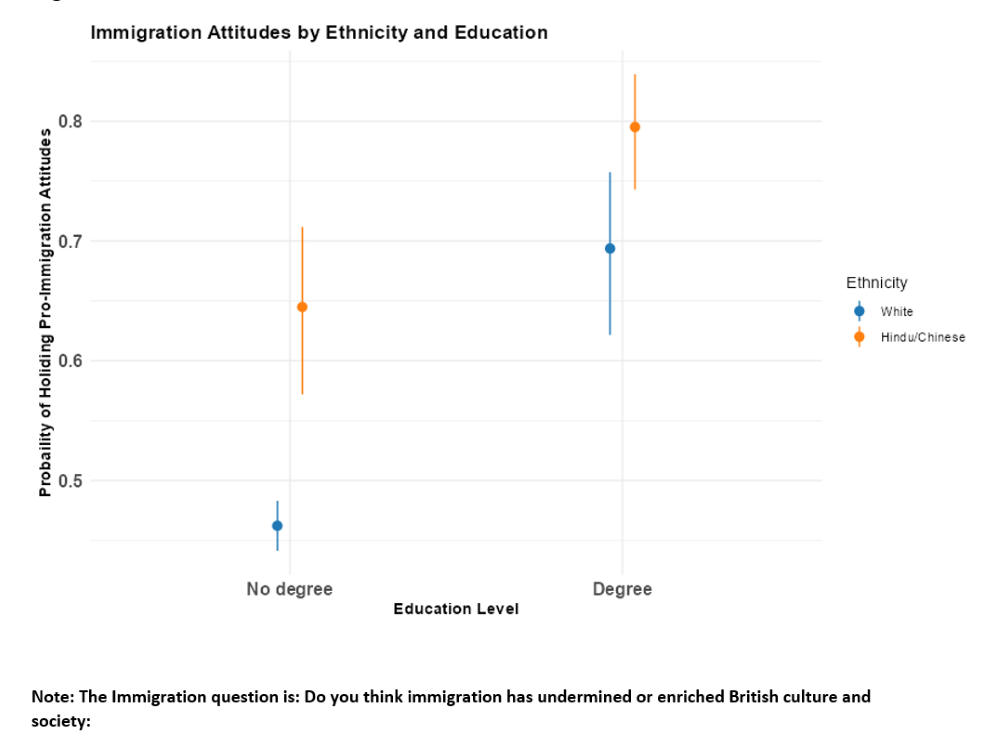

When it comes to the issue of immigration, the story is very different. Not only are university-educated British-Hindu and British-Chinse slightly more pro-immigration than whites who hold a degree, but they are also substantially more likely to be pro-immigration. Specifically, while there is only a 42 per cent chance that a white respondent without a degree is pro-immigration, the likelihood that a university-educated Hindu and Chinese respondent is pro-immigration is 80 per cent.

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

UK in a Changing Europe / Focaldata

We see, then, that university-educated Hindu and Chinese voters are not only more likely to vote Conservative than white graduates, but they are also more likely to hold right-wing preferences on economic and cultural issues. Moreover, the “liberalizing” effect associated with education does not apply to these two groups of minority voters, as university and non-degree holders are equally likely to have conservative positions on economic and cultural issues.

Finally, our analysis shows that immigration may be a potential wedge issue for the Conservatives as they attempt to reassemble their coalition of working-class whites and educated minorities. There has been considerable discussion about whether, in trying to win back Reform voters, the Conservatives risk alienating socially moderate voters who have shifted to the Liberal Democrats. The analysis above suggests that such a strategy could also alienate many ethnic minority voters on whom the party increasingly relies.

Zain Mohyuddin is a researcher at UK in a Changing Europe.