'We are actually bloody well leading this thing': The Grant Shapps interview

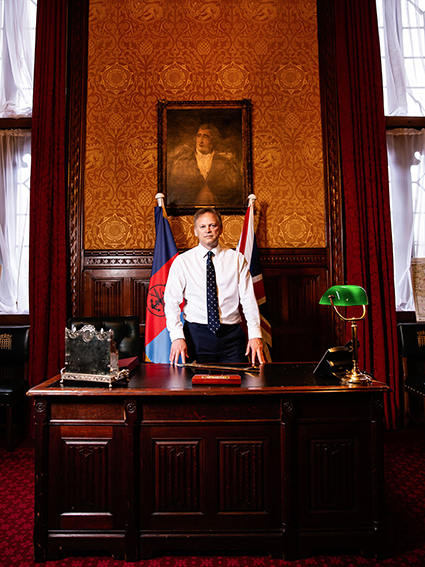

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

10 min read

The British army may be shrinking and its nuclear missiles misfiring, but Grant Shapps tells Sophie Church the UK is leading the way on modern warfare. Photography by Louise Haywood-Schiefer

The army is due to shrink to a size last seen during the Napoleonic era. It’s a fact that Grant Shapps does not much like.

“I get that the number of troops is often used as a proxy somehow for the strength of your armed forces. And I’m not against having more troops,” the Defence Secretary and 55-year-old MP for Welwyn Hatfield says.

“But I’m also not going to spend my time – that was the defence refresh in 2021, I think – I’m not going to refresh the refresh to refresh it,” he says. “So no, the decision was made; I’m sticking by that decision.”

Still, there is some frustration: “Look, I’m Defence Secretary. I’d like to have any amounts of resources”. And while Shapps says “we are committed to 2.5 per cent” of GDP being spent on defence, his request for the Chancellor to announce that figure in the Budget was denied.

It’s not about having another 20,000 troops. It’s about having the skills and the science

Britain’s war chest may be lacking, but Shapps thinks “we also have to recognise we’re pretty bloody good at this stuff,” referencing Britain’s continued support of Ukraine.

Take Steadfast Defender, Nato’s largest military exercise since the cold war, Shapps says. The British are providing 40 per cent of the land troops, an aircraft carrier, helicopters and a range of ships.

“People thinking that the number of people in the army specifically – for some reason the navy and the air force, and what happens in space, and what happens on cyber, are not thought about – is the true measure [of military strength] are not understanding the world as it is,” he says.

Based on figures in the 2024 Global Firepower review, the United Kingdom ranks sixth out of the top 10 military powers, and 30th out of 145 nations for active personnel.

Still, Shapps says: “The nature of warfare has fundamentally changed. While, generically, my answer is, of course, I always want more and greater volume [of troops] and what have you, the reality is, what is it you’re not going to have because you’re going to do that?”

For Shapps, this means prioritising investment in electronic warfare, space capabilities and drones, rather than boots on the ground. “In Ukraine, we know that cyber warfare and electronic warfare have been absolutely critical to the war,” he says. “It’s not about having another 20,000 troops. It’s about having the skills and the science.”

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

Indeed, soon after speaking with The House, Shapps unveiled a new UK Defence Drone Strategy, which promises to deliver uncrewed platform capabilities – drones, essentially – to the British army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force.

However, as the ongoing war in Ukraine is proving, technology can assist a war effort, but troops will sustain it. In January, head of the British army Gen Sir Patrick Sanders described the British people as a “prewar generation” who may have to prepare for impending war with Russia. With Sweden just introducing national service, Sanders said the UK must take “preparatory steps to enable placing our societies on a war footing”.

Currently, our Army Reserve (formerly the Territorial Army) is just 33 per cent of the size of our regular army. Allies within the Five Eyes partnership average 80 per cent.

Members of Estonia’s citizen army are exasperated by Britain’s laissez-faire attitude. Dubbed by their commander as the SAS (for training on Saturdays and Sundays), these Estonians, who have doubled in number since Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, have urged the British to learn how to fight, as the Russian war machine casts its gaze beyond Ukraine onto Nato territory in Europe.

However, a spokesperson from No 10 says “hypothetical scenarios” are “not helpful”, and Sanders has since been admonished by the chief of the defence staff for his comment.

Today, Shapps plays down any discussion of calling British citizens up to fight. “Estonia are right on the border, at the frontline essentially,” he says. “The UK is an island; we’re not in that situation. Nor do we see an immediate danger of invasion. So our training tactics – not least helping to train them – is really the core of what we do.”

He continues: “It depends what we’re trying to achieve. If we think we’re about to enter a land war, like the First World War, or actually rather like Russia are doing – just murdering their young men – then sure, if you’re in that kind of war, you would go into a conscription basis.”

When you impose sanctions, they work for a bit. And then it’s like a leaky sieve

But Britain has never entered into war with Russia alone, Shapps points out. We are also part of a multinational shield – Nato – which outranks Russia in personnel. “Russia, who are the primary on-land threat, should be under no mistake that collectively as a 32-country coalition, Nato is able to outmatch them on land, sea and air.”

As Russia’s ability to wage conventional warfare and sustain huge losses in Ukraine tests western resolve, it was – to put it mildly – embarrassing, when it emerged there had been two failed test-fires of Trident’s nuclear missiles.

Shapps, who was on the submarine when the second occurred, tells Putin he can be “100 per cent” sure the missiles would “work in reality”.

“I’m absolutely 100 per cent confident that Russia understands we have a nuclear capability, meaning that our deterrent is 100 per cent exactly that: a deterrent,” Shapps says, telling The House he wishes he could go into more detail.

He adds that he felt “great pride in the crew”, and that an American aboard who had seen 40 launches lauded this as “the most professional crew he’s ever come across, either in the UK or the United States”. But how did it feel, standing on the submarine watching our nuclear deterrent fizzle into the sea?

“Look,” he says, cutting in, “in the end, the only thing that matters, and the only thing our opponents and adversaries need to know, is: do we have a nuclear missile system that would work in reality? I can 100 per cent assure adversaries and Nato and everyone else that we absolutely do. This is exactly the same system the US uses, this is the most reliable system in the world for launching missiles and nuclear weapons – [that is] factually true.”

In January, the head of the Ukrainian navy said the war would end quicker if the UK and allies gave permission for western missiles to be fired deep into Russian territory. However, Shapps says he cannot comment.

Still, the Defence Secretary, like the Prime Minister, looks favourably on seizing the €260bn of Russian assets frozen since the outbreak of war: “I do think we should lean into seizing Russian assets and using it to pay for Ukraine.

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

“We’re talking to our international partners on that; the Chancellor, the Foreign Secretary, are both doing that at the moment,” he says, adding, “clearly there are different opportunities [to discuss], with things like the Nato 75th [anniversary] coming up.”

And what of Britain’s response to the death of Alexei Navalny? In February, the Russian opposition leader was found dead in a penal colony in northern Russia, where he had been serving a 19-year sentence. “Make no mistake, Putin murdered Navalny,” Shapps says gravely.

In consequence, the British government sanctioned the six men running the polar camp where Navalny lived out his last days.

Just as Putin’s most dangerous critic was dying in an Arctic gulag, Russian troops captured the Ukrainian city of Avdiivka, a significant victory. Does Shapps believe sanctioning six prison operators in the Arctic will make any serious difference to the Russian president?

“I don’t think anyone is suggesting that sanctioning those six people is going to stop Putin, of course it’s not,” he says. “But making sure that Putin, his cronies, business people who support him – you know, there are still aircraft and yachts that are still tied down and moored that I held when I was transport secretary, and I can tell you, it certainly annoys the people who own those things.”

While Russians may find sanctions irritating, they are certainly finding means of evading them. Last month, it became apparent that Russia is receiving goods for use in its war effort from neighbouring countries, thus avoiding economic sanctions. According to figures from the International Monetary Fund, Russia’s economy was the fastest growing in the G7 last year, despite international sanctions. It is forecasted to grow faster than the G7 again in 2024.

More concerning still is that British exports of weapons may still be flowing to these border countries, and then on to Russia. While Britain is proudly supporting Ukraine with weapons, it may also be supplying its enemy.

The Defence Secretary is candid about the declining utility of sanctions imposed two years ago. “What’s happening from the United Kingdom is a fraction of a much bigger picture,” Shapps insists. “When you impose sanctions, they work for a bit. And then it’s like a leaky sieve: people find companies in the country – in this case, Russia – and find a way to get around the sanctions.

“We have, on various different occasions, tightened sanctions, reviewed sanctions, and what have you, and clearly we will carry on doing that,” Shapps says. “This is where Britain can be more creative; if things are coming in through the border countries, we should lead the charge to look at creative ways to do that.”

Russia’s allies in the Middle East continue to support Putin’s warmongering. In February, Iran supplied Russia with around 400 surface-to-surface ballistic missiles, in addition to the weapons already sent.

Shapps says he cannot go into specifics but acknowledges the “bad influence”: “If there’s struggle in the world, often Iran are egging it on, or helping to supply the food chain in this case. They are a bad influence, not just on their region, but in this case in Europe as well.”

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

Grant Shapps (Photography: Louise Haywood-Schiefer)

Just look to the Red Sea, he says, where the Houthis say they will continue to block global trade until Israel stops its war in Gaza. “They can’t actually control what they unleash,” he explains. “And they create almost Frankenstein proxy groups, which they fail to then control as well.”

But when you see hostile states and their offshoots in league against the West, surely the UK must go further than simply using sanctions “creatively” or to “annoy”?

“Well, look, I completely take your argument,” he concedes. “But who are the two countries in the entire world who actually take some action against the Houthis? The United Kingdom and the United States.”

In making the case the UK goes further than most, he cites British provision of long-range Storm Shadow missiles to Ukraine, instrumental in breaking Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea. Now, he says exports in the Black Sea are back up to 4.6m tonnes, close to the export rate before the war began.

“When I speak to President [Volodymyr] Zelensky, or the Deputy Prime Minister [Oleksandr] Kubrakov, they are very clear: that would not have happened without Britain,” Shapps says. “I mean, we are actually bloody well leading this thing,” he says, with a frustrated laugh.

Shapps relentlessly asserts that the UK is doing more than any other country to help Ukraine. But that resolve to keep leading the resistance is going to be tested like never before in the months to come.