When the nation's favourite TV and elections collide

4 min read

Millions of voters nationwide will be glued to screens over the next few weeks as Euro 2024 gets underway. It is not uncommon for political parties to panic about the threat posed to their turnout by major TV events.

Sixty years ago, in the run up to the 1964 election Harold Wilson was canny (or paranoid) enough to spot that in the last hour of polling the BBC would be repeating an episode of its phenomenally popular comedy, Steptoe and Son. Wilson reckoned that the story of Albert Steptoe’s unexpected win on the Premium Bonds would be enough to keep working-class Labour voters at home and thus scupper his chances of victory. A successful lobbying campaign by Wilson led to the programme being pushed back until the polls had closed.

The story is fairly well-known, having first appeared in in 1977, when his longstanding secretary, Marcia Williams, had given the exclusive to The Observer under the headline: ‘Marcia: How We Stopped Steptoe’.

Less well known is that three years before that scoop, in 1974, Steptoe had again ruffled Wilson’s feathers. The episode ‘And so to bed’ saw Harold Steptoe invite a certain “Marcia Wigley” back to his for sex only to have to wait for his father go to bed and then see his own collapse at the vital moment. The BBC was sternly informed that Wilson and Williams were not amused.

The problem that voters might be distracted from their democratic duties did not begin in the 1960s, however. In 1935, an article in the Guardian noted that the biggest obstacle to canvassing was “neither the indifference nor the ignorance of the electorate, but the inside interference of the BBC”.

“When a good variety bill or a thriller is on the air the householder obviously resents the interruption and one never gets over the threshold”. Bulldog Drummond – “he could kill a man with his bare hands in a second” – was singled out as having caused problems. One canvassing team gave up and sat inside the voters’ house, listening to the radio with them until the programme had ended.

The potential for television to be a particular problem for campaigners was noticed by Henry Fairlie – one of the UK’s first identifiable political commentators – in 1959.

Television audiences, he noted, were growing in size. Labour voters, in particular, voted late in the day, when the TV was on. “Bad weather outside and good television inside could swing the balance against Labour”. Labour, he claimed, should be worried about the Western Rawhide and the quiz show Dotto. “Dotto, under the wrong circumstances, could cost us the election”, Fairlie claimed to have been told by a Labour insider.

“After three weeks of election coverage on television [three weeks! if only…] the viewer might well be heartily sick of it and only too anxious to settle down to Wagon Train or Dotto."

More broadly, there has always been a tricky relationship between broadcasting and elections. Restrictions on what was allowed to be seen or heard during an election campaign used to be exceptionally strict.

Initial rules banned “anything (except the official election broadcasts) which could fairly be considered likely to influence voters”, a phrase that was interpreted very tightly. In the 1955 campaign, for example, the BBC cancelled the broadcast of an Oxford Union debate on the motion that “the methods of science are destructive to the myths of religion”, along with a detective serial which mentioned Communism and a play in which a gypsy forecasted elections. In 1959 even appeals to increase participation – of the “use your vote” variety – were considered beyond the pale.

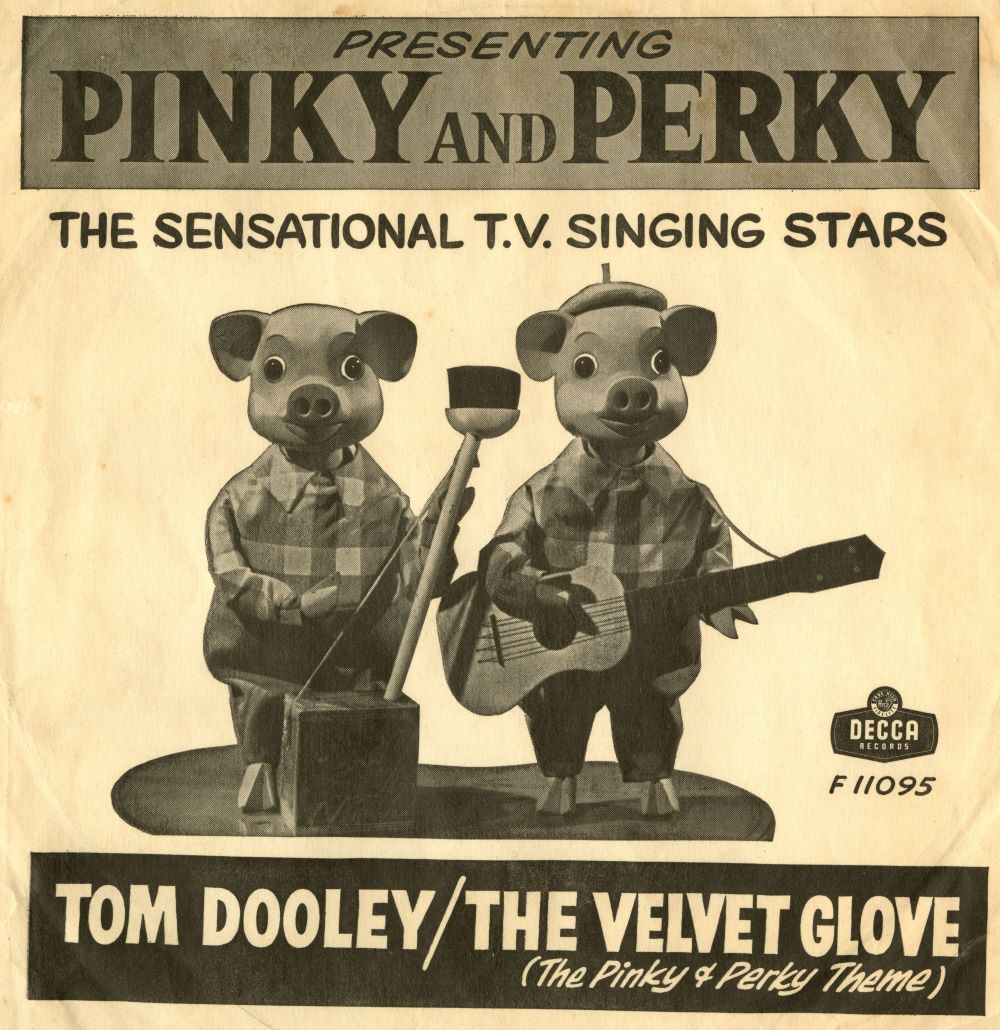

The rules gradually relaxed, but in 1964 a Michael Bentine sketch in which a Chinese Junk bombarded the House of Commons, while MPs were supposedly discussing “Oriental raspberry blowers” was too much. And in 1966 an episode of the children’s programme Pinky and Perky – featuring two high-pitched anthropomorphic puppets – was to set be withdrawn. Initially, the BBC announced that “You too can be Prime Minister” – in which Pinky and Perky became joint-Prime Ministers – was being canned, only to retreat in the face of widespread incredulity. But not before the director of BBC1 had sat down and watched the programme in full himself.

As luck would have it – or rotten luck, depending on your point of view – no games at this year’s Euros will be played on Thursday 4 July. If England and / or Scotland make it as far as the quarter finals, those fixtures will take place on Friday 5 or Saturday 6 July — just as the new government will be settling in.