Wrong side of the track: How HS2 became a nightmare for those farming its route

Illustration: Tracy Worrall

8 min read

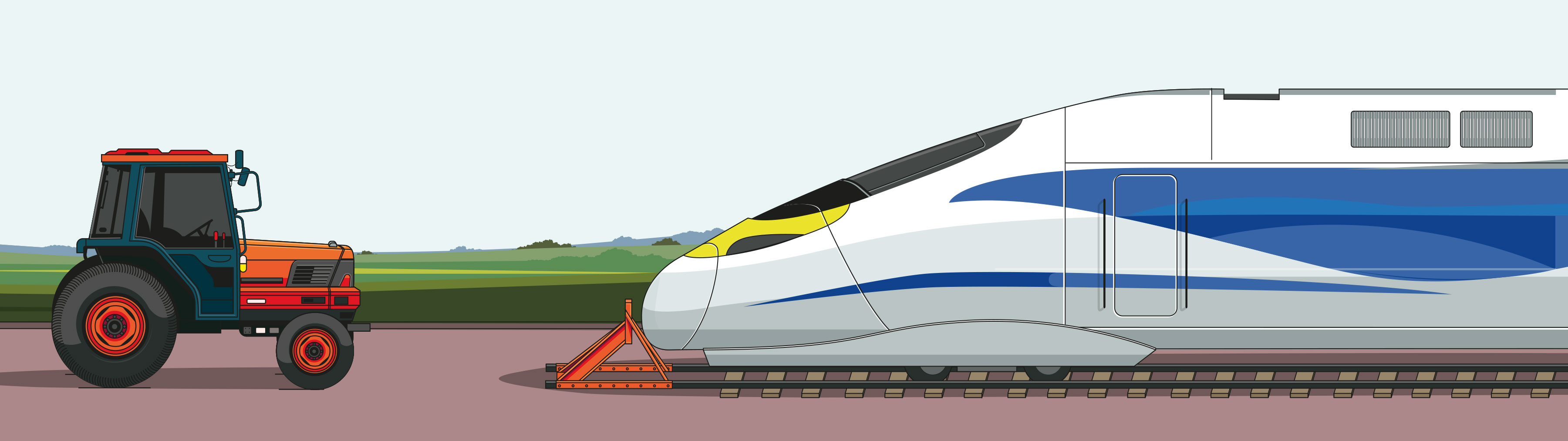

Once a totem of levelling-up, now a national embarrassment, HS2 has become a political disaster. But, as Sophie Church reports, few have suffered as much as those living along its route. Illustration by Tracy Worrall

The sorry story of HS2’s chaotic journey, from national flagship to national embarrassment, is usually told in terms of economic and political costs.

As the budget heads towards £100bn – to deliver just a fraction of the line some promised would rewire the country’s entire economy – its agonies seem never-ending.

Last October, Rishi Sunak announced that the north-westerly fork of HS2 – leading from the West Midlands to Manchester – would be scrapped. The other fork, leading from the West Midlands to Leeds, was axed in 2021. The line from Euston to Birmingham is still going ahead.

But while critics have been quick to deride the government for turning HS2 from a point of national pride to a symbol of national decline, it is those living along the stretch of HS2 who are truly suffering from the delays, changes and uncertainty.

It’s entirely done by people who are almost alien to the British countryside

The impact on farmers has been especially stark. To this day, many are still awaiting compensation for land acquired via compulsory purchase order. While there are no precise figures for the number of farmers awaiting compensation, a freedom of information request reveals that only one in four landowners in Madeley, a village in Staffordshire, has been fully compensated by HS2.

Others have had their land temporarily acquired by HS2 to relocate gas pipelines, for instance, or carry out archaeological excavations.

Farmers are losing income from unfarmed land and, in many cases, HS2 has not paid them for loss of revenue. And when land has been returned, it has been scarred – left unworkable and unsaleable.

Illustration: Tracy Worrall

Illustration: Tracy Worrall

Now, those in the agricultural industry for decades are seeking alternative means of employment.

Others say their health has suffered due to stress from HS2, and some have died during the process. MPs from all parties have raised their plight. Referring to one of his own constituents, Greg Smith, Conservative MP for Buckingham, tells The House: “They will never prove that it was directly HS2 but, come on, it’s pretty obvious where the stress points in that poor man’s life were.”

At the start of this year, the Department for Transport (DfT) made good on its promise to lift ‘safeguarding’, the process by which major infrastructure projects protect land they intend to use, between Birmingham and Crewe. By lifting safeguarding, “the government are providing certainty to people along the former route of phase 2a”, said HS2 minister Huw Merriman.

For Joy Fielding, whose farm is in Lichfield, at the start of the proposed Birmingham to Crewe route, this appeared to be the end of 14 years of anxiety. As plans stood, the railway would have torn through woodland on her farm, creating deep borrow pits, spoil heaps and high embankments in the process.

So, when Sunak announced this phase would be scrapped, Fielding “naively thought that was the end of it”. But in January, a letter arrived telling Fielding her land was being safeguarded under phase 1: the route leading from Euston to Handsacre Junction, which connects HS2 trains to the existing West Coast Main Line.

“It’s more uncertainty,” she says, distressed by decisions made about her, not with her. “It’s: ‘This is going to happen to you, that’s going to happen to you, this is going to happen, and you’re going to have a borrow pit, and you’re going to have this and you’re going to have that.’”

Falling into safeguarding twice makes Fielding one of the more unlucky farmers. But even with safeguarding lifted, those compulsory purchases of land that are “well advanced” will continue along the Birmingham to Crewe stretch until completion, says HS2.

However, the process of receiving compensation for compulsory purchases has been neither fair nor equitable for many farmers.

Robert Lockhart, a farmer in Tamworth, says that when land is purchased by HS2, landowners are paid 90 per cent of the market value up front, with the extra 10 per cent to follow.

But Lockhart says he was only paid two-thirds of the true value of his land. He then discovered he had to pay capital gains tax. “Considering I didn’t want to sell it,” he says, with a stony laugh, “I thought, that’s a rip-off.”

Farmers have been working with land agents and lawyers to negotiate with HS2, but have been fronting the costs themselves. While Fielding has put claims in with HS2 to recoup her outlays, she hasn’t seen any returns. “It’s £300 in an £80bn scheme and they’re arguing between themselves as to which department is going to pay it,” she says.

While the project is naturally complex, both Graham Stringer, Labour MP for Blackley and Broughton, and Liberal Democrat MP for Chesham and Amersham Sarah Green say HS2 is “a bad neighbour”.

For Fielding, it was the constant barrage of dehumanising letters. “They weren’t even addressed to me, they were addressed to ‘Dear Occupier’,” she says. “They could have spoken to us, and treated us like individuals who were really badly affected.”

A large part of Durham Farm in Wendover Dean has been taken by HS2 (Credit: Maureen McLean / Alamy Stock Photo)

A large part of Durham Farm in Wendover Dean has been taken by HS2 (Credit: Maureen McLean / Alamy Stock Photo)

For Lockhart, it was the general sense of chaos. “The amount of people who came and went – they’d either started two weeks ago or they were leaving in two weeks… You never got a straight answer from anybody, because it wasn’t their responsibility; it was somebody else’s. Nobody knew anything or divulged anything. It was pretty chaotic, to be honest.”

Smith says HS2 lacks knowledge of how the railway would affect farmers. “It’s entirely done by people who are almost alien to the British countryside, and certainly working practices in the British countryside, because they’re all planning it on a tabletop in Birmingham,” he says.

Farmers think a taskforce is needed to untangle the highly complex compensation cases.

Smith agrees, saying “some form of very rapid deployment scheme” is required to get people the money they are owed. “I have a lot of faith that Huw Merriman as the rail minister of HS2 wants to get this right,” he continues. “[But] he’s hamstrung by the fact there is an Act of Parliament that dictates the terms of this.”

A DfT spokesperson says: “Ministers and officials regularly meet with the National Farmers’ Union to discuss the decisions taken on HS2. We are developing a clear programme for selling land no longer needed for the project and will set out more details in due course. We will ensure our approach provides value for the taxpayer and will fully engage with individuals and communities who are affected throughout this process.”

But with a Labour government looking likely, farmers are now contemplating whether HS2 will be resurrected. And while the end to safeguarding means that land is now free for development – a cynical move, critics say, to prevent future governments from restarting the project in full – there is a push from Northern quarters to stay committed to HS2.

Earlier this month, West Midlands and Greater Manchester mayors Andy Street and Andy Burnham warned that, “to do nothing is not an option”, and put forward three, largely privately funded, options for reviving the railway.

Andy Street (Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo)

Andy Street (Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo)

Shadow rail minister Stephen Morgan says Labour would “not repeat” the mistakes made by the Conservatives, and has launched an independent expert review of transport infrastructure to “ensure a Labour government can deliver transport infrastructure faster and more effectively”.

Stringer is more revealing about HS2’s fate. “I think there is a real possibility that the mayors will get it right and Labour will row in behind,” he says. “I am hopeful that Keir Starmer will change his view on this. It’s difficult to see how you can regenerate the North without HS2.”

There is reason to believe that rebranding HS2 will break any negative association. Just look at how Crossrail – initially bogged down in controversy – rebranded into the much-loved Elizabeth Line, points out Lib Dem Sarah Green.

“Maybe it doesn’t need to be anything more sophisticated than just slapping a different name on it,” she says. “It was a stroke of genius calling it the Elizabeth Line.”

Labour’s levelling-up proponents may struggle to make the case for HS2 to a front bench cowed by economic caution. But for those farmers already affected, whether it goes ahead or not is almost a moot point.

“The trouble is the land is blighted, full stop. The whole farm is really blighted,” says Fielding. “And now that we’ve got this safeguarding plonked on us again, we can’t do anything. We can’t diversify. We can’t go into farming schemes. That’s one of the problems we’re back to: how can we plan for the future?”

A spokesperson for HS2 Ltd says: “We understand that the situation may be difficult for property owners and we continue to negotiate with them to conclude claims, and urge them to provide the standard level of supporting documentary proof to help resolve outstanding claims.”