Earl of Clancarty reviews 'Brasil! Brasil!'

The Lake Tarsila do Amaral, 1928 | Image: Jaime Acioli. © Tarsila do Amaral S/A

4 min read

Prepare to have your assumptions challenged by this nuanced and searching Royal Academy exhibition of 20th-century Brazilian art

Anyone expecting the current exhibition of 20th-century Brazilian art at the Royal Academy to be (stereotypically) a celebratory riot of colour and carnival – perhaps prompted by those exclamation marks in the title – will be enjoyably wrong-footed. Rather, this is a nuanced, searching exhibition, posing – in particular – questions about national identity which, in a global environment where the world order is changing, are as relevant today as when they were asked 100 years ago.

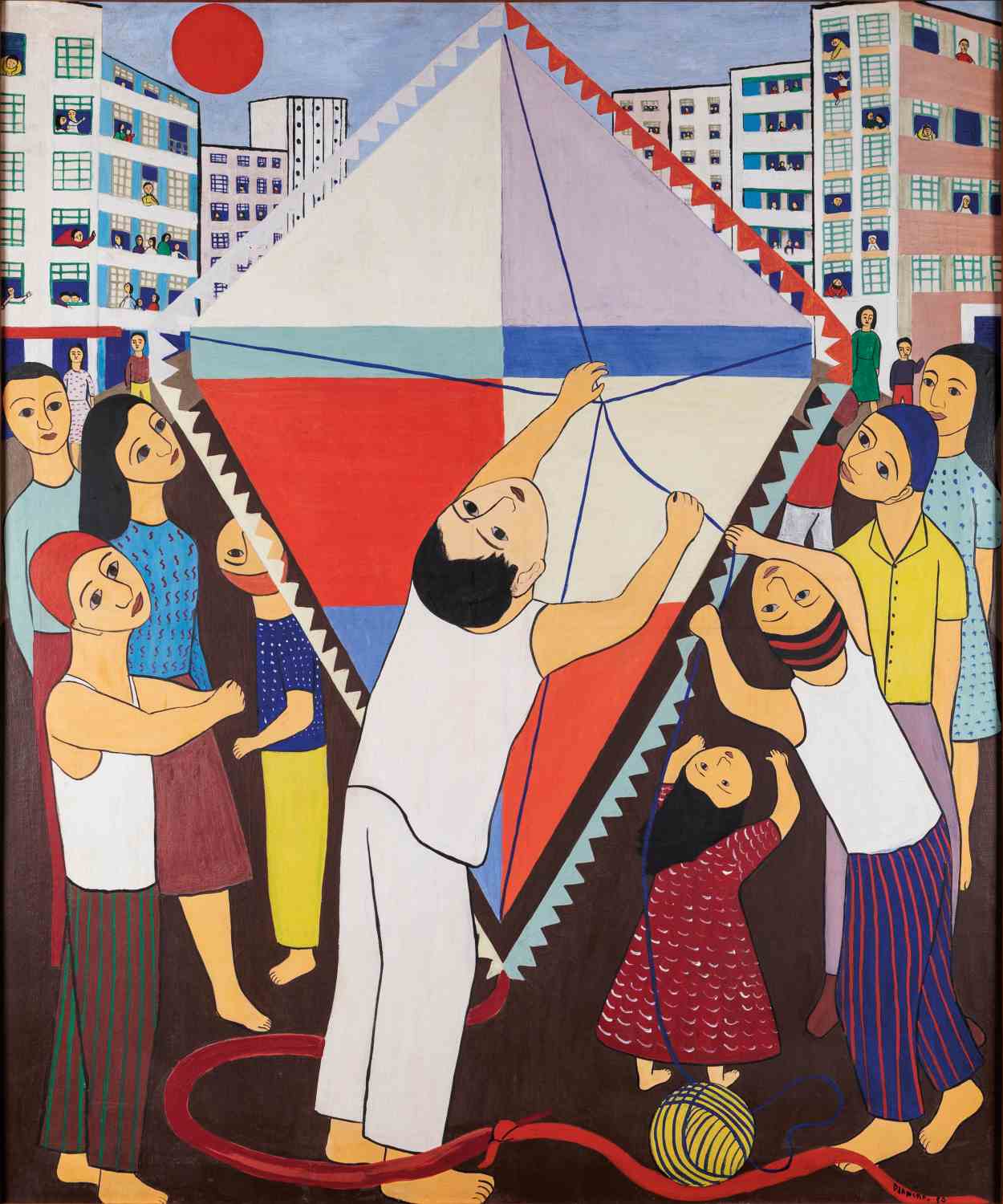

Flying a Kite Djanira da Motta e Silva, 1950 |

Flying a Kite Djanira da Motta e Silva, 1950 |

Image: Humberto Pimentel/Itaú Cultural. © Instituto Pintora Djanira

Brazilian art is not a stranger to our shores. We have just had an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery of the work of famed contemporary artist Lygia Clark, and indeed the Royal Academy itself held a sizeable exhibition of modern Brazilian art back in 1944.

But that was then, and the Royal Academy has come back with an even larger survey – although one that concentrates on the work of just 10 modern artists, all of whom have strong reputations in their own country but are not well-known here.

I confess, as a relative newcomer to Brazilian art, I did find myself initially looking out for those stereotypes that in my head are located somewhere between a frenetic Sérgio Mendes record and the clean-lined white modernism of the buildings of Oscar Niemeyer. This exhibition is neither and both: yes, the colours are there – the numerous shades of earth reds; the ubiquitous turquoise greens of the banana groves. But not the movement.

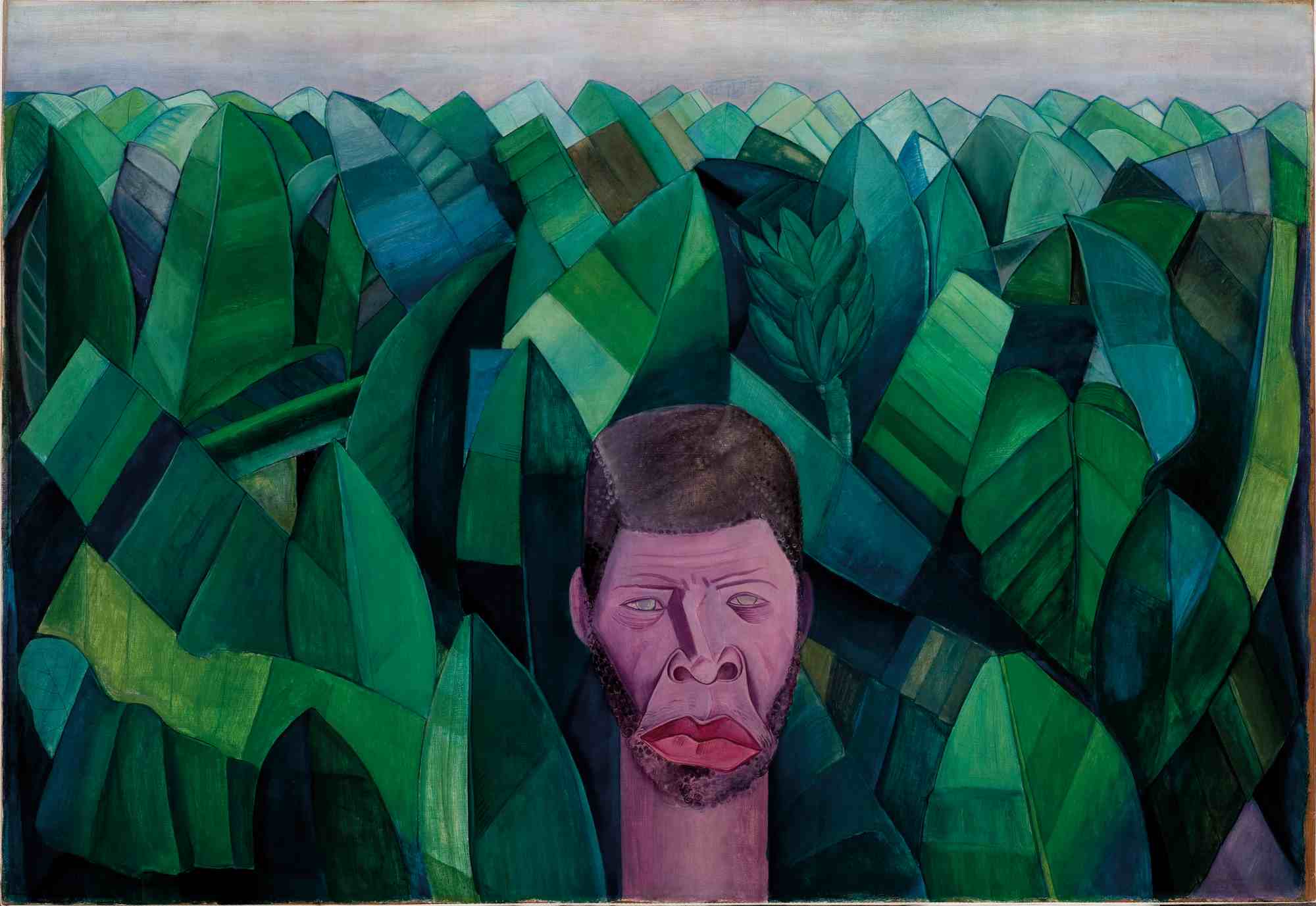

Banana Plantation Lasar Segall, 1927 | Image: Isabella Matheus. © Lasar Segall

Banana Plantation Lasar Segall, 1927 | Image: Isabella Matheus. © Lasar Segall

Indeed, so much of the work has a feeling of anticipation and expectancy, as though something important is about to happen. This is particularly true of the paintings of Djanira da Motta e Silva with their tableau-like depictions of folk customs and everyday life. That same sense of an unnatural stillness is there too in the work of Lasar Segall, whose forest paintings border on the abstract.

So much of the work has a feeling of anticipation and expectancy

It is true again for Tarsila do Amaral, whose paintings were directly influenced by early European surrealism including Giorgio de Chirico. A luscious work such as The Lake, 1928 – the poster work for the exhibition – also has considerable resonance with the current interest in a form of contemporary landscape painting which hovers between the real and the visionary. But Tarsila, like Segall, turned, in the 1930s, to a form of social realism in the wake of the Great Crash which so affected Brazilians including the artists themselves.

The strangest and perhaps most individual work here is that of Flávio de Carvalho who, like many of the artists represented, had various occupations, including being an engineer, a playwright and a journalist, as well as studying in Europe, as others did.

The strangest and perhaps most individual work here is that of Flávio de Carvalho who, like many of the artists represented, had various occupations, including being an engineer, a playwright and a journalist, as well as studying in Europe, as others did.

Oswald de Andrade’s 1928 Manifesto Antropófago (or Cannibalist Manifesto) – inspired by a Tarsila painting – talks of the “absorption of the sacred enemy” that is European culture, as opposed to embracing or rejecting it. This is a sophisticated response to the clearly fraught relationship that existed between these artists and Europe, suggesting a way through to their own sense of identity.

Earl of Clancarty is a Crossbench peer

Brasil! Brasil!: The Birth of Modernism

Curated by: Dr Fabienne Eggelhöfer, Roberta Saraiva Coutinho & Dr Adrian Locke

Venue: Royal Academy of Arts, until 21 April 2025