Indian election: How will the Conservatives and Labour handle another Modi triumph?

12 min read

Successive Tory PMs have put aside qualms over Narendra Modi in the pursuit of boosting trade with India, with little success. But, as Sophie Church reports, a Labour government might find India’s controversial leader an even more difficult problem

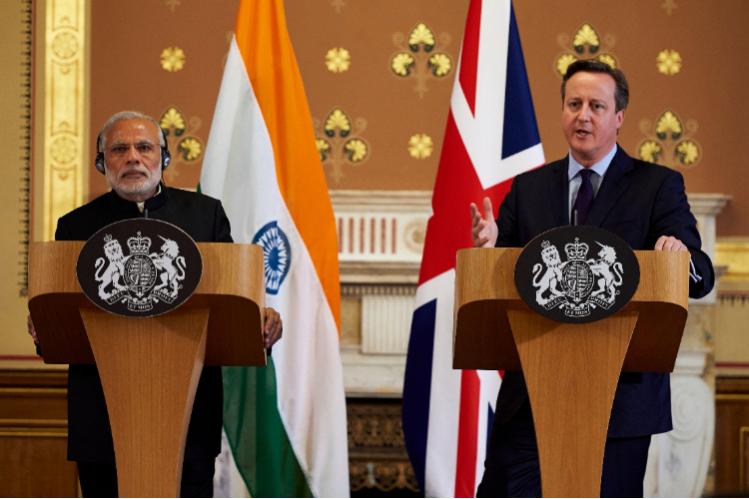

“Namaste Wembley!” David Cameron was in full stadium mode when he presented Narendra Modi to a 60,000-strong crowd in 2015.

That visit was part of Modi’s debut on the world stage. Nine years later, on the cusp of what looks certain to be a romp to a third consecutive term, India’s prime minister needs no introduction.

As officials arrive in London from Delhi for the latest round of talks for a new United Kingdom/India trade deal, and elections get under way, it is a good time to review this complicated relationship.

There is a wariness in Delhi to say, ‘OK, so you’re a minister, but there’s so much change that you might not be a minister in six months’ time’

Cameron had made India an early focus of his premiership, pledging in 2010 to double trade by 2015.

After the UK left the European Union, Theresa May’s first trip outside Europe was to India. The same was planned for Boris Johnson, but Covid intervened. Liz Truss travelled to India multiple times as foreign secretary.

Narendra Modi and David Cameron in 2015 (Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

Narendra Modi and David Cameron in 2015 (Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

But bilateral trade between the two countries has increased by just 22.7 per cent from 2009 to 2020, according to reports from Deloitte, the business advisory firm. There’s no disguising that is a poor return on 14 years of diplomatic effort – most of them between governments led by parties that, if not quite sisters, are mutually supportive.

But while Cameron may have fallen short on his trade promises, he was prescient about another matter when the Tory leader and the leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India’s governing party, joined together in Wembley.

“It won’t be long before there is a British-Indian prime minister in 10 Downing Street,” predicted Cameron that night.

Rishi Sunak, the UK’s first Hindu prime minister, is, unsurprisingly, popular in India but there is little chance that this Conservative leader will be any more successful in winning the gains offered by the world’s largest democracy and one of its fastest-growing economies. With 14 rounds of trade deal negotiations already behind them, Indian officials visited London to iron out final details in April. “I think that the trade deal is so important that it will be done,” says a senior Foreign Office source. “I can’t tell you quite how or when, but what I can tell you is that, because of its importance to both parties, a way will be found.”

Shailesh Vara, the Conservative MP for North West Cambridgeshire, adds: “I understand that much of the detail has been resolved and that there are just a small number of issues that remain outstanding.”

Viewed from Delhi, however, the persistence of Tory ministers has become tiresome, says Pratik Dattani, of Bridge India, a think tank, especially given the party’s prospects of holding on to power at the next election.

“There is a wariness in Delhi to say, ‘OK, so you’re a minister, but there’s so much change that you might not be a minister in six months’ time or a year’s time, so there’s not much point in engaging with you’,” says Dattani.

Nevertheless the efforts begun by Cameron and continued by his successors have created “a funnel into the party, whether that’s donors, whether that’s engagement with politicians, whether that’s prospective candidates in the future”, says Dattani. “That outreach into the Indian community was really good and channelled well.”

This translated to success at the polls for the Conservatives, seen increasingly by Indian-origin voters as the party of aspiration.

With Jeremy Corbyn irritating Delhi through his interventions over Kashmir, the Conservatives were helped by the UK branch of the Overseas Friends of BJP, who campaigned against the Labour Party and in favour of Tory candidates in 48 marginal seats at the 2019 general election.

However, Modi’s espousal of Hindu nationalism has led to accusations of connivance in communal violence – including riots when he was chief minister of Gujarat in which hundreds of Muslims were killed. Opposition leaders, including Congress leader Rahul Gandhi and Delhi’s chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, have also been arrested on charges many believe are politically motivated.

But certain Conservatives wholeheartedly disagree with critics that allege Modi has been undermining democracy in his pursuit of complete control. Conservative peer Baroness Verma says discussion of a democratic backsliding in India is simply not true.

“I call them the politics of people trying to waft up things that aren’t there,” she says. “I come from the Sikh faith; some of the richest Indians in India are from the Sikhs. I don’t see these funny headlines about it rolling back; I see a real roll forward of young people with a lot more confidence in who they are and where their place in the world is.”

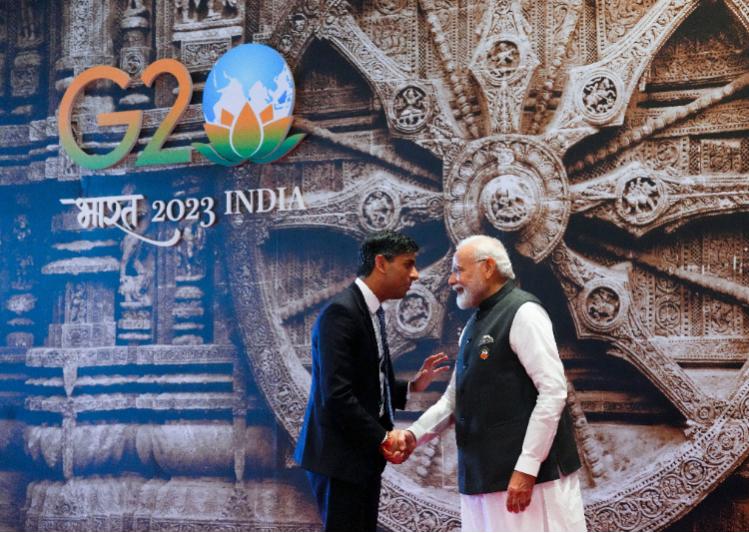

Rishi Sunak and Narendra Modi (Credit: The Canadian Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

Rishi Sunak and Narendra Modi (Credit: The Canadian Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

Western democracies should learn from – not lecture – the BJP, she says. “I just read an article not that long ago about the importance of women, and how [Modi is] putting women at the forefront of education, of improvement in safety and all of those other things. I wish that this was something that was a conversation happening across democracies.”

Sunak’s mother-in-law, Sudha Murthy, was recently nominated to sit in the Indian parliament’s upper house by President Droupadi Murmu. While most members of India’s upper house are elected, 12 are nominated by the president for a six-year term as a nod to their contribution to public life.

A trained engineer, Murthy is best known for establishing the Infosys Foundation – which has helped build thousands of houses in flood-affected areas of India, and created libraries in rural locations.

Modi says Murthy’s appointment is an example of “‘Nari Shakti’ [women’s power], exemplifying the strength and potential of women in shaping our nation’s destiny.”

Conservative Friends of India director Nayaz Qazi adds: “She broke the glass ceiling and played a significant part in the enhancement and development in India.”

Sunak’s father-in-law meanwhile, IT billionaire Narayana Murthy, is well-connected to the government. “It’s simply the case that you don’t get to be a billionaire in India and remain a billionaire without having close ties to the government,” says Vikram Visana, lecturer in political theory at the University of Leicester.

But while insiders say Murthy has no political relationship with Modi, at the last Indian election Sunak’s father-in-law expressed support for a continuation of the Modi premiership: “We must be grateful that there is at least a national leader of Modi’s calibre who is interested in improving India. Looking at the last five years, I feel that having a leader who is focused on nation, focused on discipline, cleanliness [and] economic progress is a good thing.”

With these familial links, even if Sunak did have reservations about Modi’s governance, some, like Visana, think he would never be able to voice them: “I don’t think Rishi would – even if he was inclined to – be quite openly critical of the Modi regime. I think the fact that he’s a Hindu, and took his oath on the Gita and so on when he first joined Parliament, does tend to mean that a lot of this stuff is slightly ignored to a certain extent.”

Conservative Friends of India Conference Reception (Credit: Nayaz Qazi)

Conservative Friends of India Conference Reception (Credit: Nayaz Qazi)

With the BJP likely to win the next election, and a Labour government looking likely in the UK, Keir Starmer has been turning his attention to India. But there has been work to do for the Labour leader in, as he says, “resetting the relationship” with India, including damage caused by Jeremy Corbyn’s criticism of India’s actions towards Muslim-majority Kashmir.

This has meant a flurry of flights to India for Starmer’s front benchers, tasked with building ties with Indian businesses and politicians. Angela Rayner and Stockport MP Navendu (Nav) Mishra flew to India in February, with Rayner calling for future economic collaboration between the countries.

Most recently, shadow foreign secretary David Lammy met with his opposite number Subrahmanyam Jaishankar in London. Lammy then travelled to Delhi to meet Jaishankar, where the pair enjoyed a lunch together.

“The idea behind doing all this engagement is that if we do win we can enter government with those relationships already solid, so we’re not starting from scratch. It was all very, very warm and good and constructive,” says a source close to Lammy.

Lammy was intrigued by how industrial policy is transforming India, and sees opportunity to collaborate on climate security and new technologies. He was particularly “struck” by how quickly trains have been electrified in India.

But Labour remains tight-lipped, for now, on any trade deal with India, which it doesn’t think will pass under the current government. “We’re not keen to shadow negotiate from opposition,” says a source close to the shadow cabinet. “We were quite clear, actually, in our meetings with the trade minister that we’re not getting into the details at this stage. That’s something we’d do in government.”

I hear from people that I know in the Indian High Commission that they’re really pleased to see the Labour Party change

Starmer’s eagerness to repair relationships with India is proving fruitful. “I hear from people that I know in the Indian High Commission that they’re really pleased to see the Labour Party change,” says Parmjit Dhanda, the former Labour MP for Gloucester. “I think there is real optimism for the future. And I don’t think anybody can really doubt the Labour Party is a very different creature to what it was a few years ago. That is very much welcomed.”

But where senior Conservatives with links to India – Priti Patel for instance – can build on existing relationships in India, deepening engagement may be more difficult for Labour: out of power for 14 years and with few shadow cabinet members experienced in Indian relations.

The current political scene is a long way from 2009 when David Miliband, then foreign secretary, and Rahul Gandhi, then the political heir-apparent, spent a (much mocked) night in an Indian village.

“Angela certainly has no background in terms of South Asia whatsoever. Nav is from her constituency, or next to her constituency, but Nav is 33, he went to a private school in the UK,” says a think tank source. “And David Lammy also has no meaningful foreign policy experience.”

Where the Conservatives connect with India through the Conservative Friends of India in the UK, the picture for Labour is more fragmentary. The party has its own equivalent – Labour Friends of India – but there’s also the Labour Convention of Indian Organisations, Hindus for Labour, and Tamils for Labour.

David Lammy playing cricket in Mumbai

David Lammy playing cricket in Mumbai

“You have this very confused mix of four or five organizations, which try to have Indian outreach,” says Dattani. “And so I think the Labour Party doesn’t seem to have a plan.”

In the UK, the Conservatives have historically targeted seats with large Indian diaspora populations, potentially more aligned with the BJP. “There is a direct link with not just international affairs, but actually with electoral calculus in terms of where one positions themselves in terms of geopolitics,” a former Home Office spad explains. “So that diaspora piece can be quite critical.”

Corbyn’s perceived anti-India stance had ramifications among the British Indian diaspora. In 2019, support for Labour among British Indians had dropped to 30 per cent from 61 per cent in 2010.

“My mum’s phone was going off with things saying: ‘Indians – don’t vote Labour’, or, ‘Indian Hindus – don’t vote Labour because they’re Hindu phobic’, or, ‘they’re anti-India’,” says Visana.

But under Starmer, more Indian-origin candidates are standing for election, among them, Rajesh Agrawal, the former deputy mayor of London running in Leicester East. “I think that will further help the Labour Party strengthen its relationship with the British Indian community as well as within India,” Agrawal says.

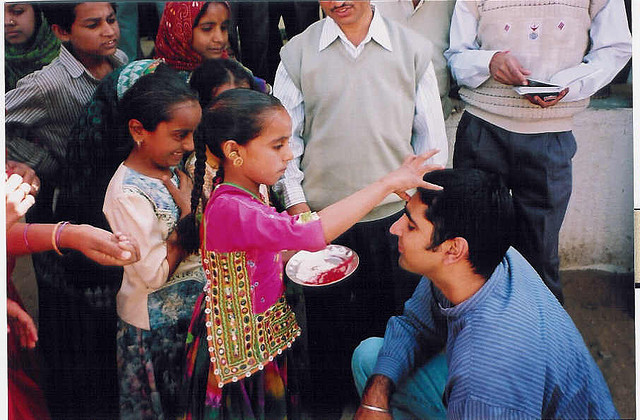

Parmjit Dhanda, Labour Friends of India visit, 2002

Parmjit Dhanda, Labour Friends of India visit, 2002

Still, some say Labour’s engagement with the Indian diaspora lacks depth. “Going to a church, a temple, a mosque or a synagogue for half an hour, 45 minutes, doing a photo and shuffling off is very different to having meaningful engagement,” says one Labour MP. “What does meaningful engagement mean? It means having a difficult conversation that you would rather not have, but actually getting the good and the bad and the ugly out.”

Building engagement with Modi’s government, both in India and within the diaspora in the UK, carries risks for Labour. Closer collaboration with India through a trade deal will prove an economic and reputational boon for the incoming PM. However, Starmer may start seeing splits within his party if he does not address Modi’s permissiveness over violence against Muslims in India.

“A British government should push back very rightly on the arrest of civil society leaders, on the freezing of opposition party bank accounts, and on the jailing of opposition party leaders on very flimsy evidence, or no evidence in some cases,” says Dattani.

“If Labour chooses not to do that, then Labour will have the same problem it has with Gaza, in that it’s kind of messed around with what it thinks about Palestine and Israel, and really has not made anyone within Labour happy.”

But if a Starmer government speaks out, it may jeopardise its fledgling relationship with the BJP. “The Modi government can be extremely spiky when these issues are raised by other governments”, Edward Anderson, author of Hindu Nationalism in the Indian Diaspora, says.

“When it comes to Britain, there’s an historic relationship that underpins all of this, and often a sense that ‘former colonisers shouldn’t be telling us what to do’.”

While a wholly positive attitude towards the Modi government is politically problematic domestically, politicians across the divide agree: Modi is the democratically elected leader of an ambitious, expanding India – a country heading for superpower status. With the UK looking to re-establish its place in the world post-Brexit, it looks likely that Modi’s India will play a part in Britain’s future.

PoliticsHome Newsletters

Get the inside track on what MPs and Peers are talking about. Sign up to The House's morning email for the latest insight and reaction from Parliamentarians, policy-makers and organisations.