Why is the British electorate so volatile?

5 min read

By going from a landslide defeat to a near-historic majority in one parliamentary term, Labour’s victory continued the trend of extreme volatility that has come to define recent British elections.

One explanation that has been put forward for the increasing level of vote-switching occurring across advanced democracies is that a greater proportion of the electorate is “cross-pressured.” Cross-pressured voters have socio-demographic characteristics or issue preferences that push in different directions. For instance, they are aligned with one party on economic issues and another on cultural issues. Since no party aligns with their preferences on all issues dimensions, they are less likely than “ideologically consistent” voters to remain loyal to one party.

In recent elections, Red Wall voters – culturally conservative, working-class voters in the North and Midlands – have been the most closely analyzed group of cross-pressured voters. Their large-scale defection to the Conservatives in 2019 was central to their 2019 victory. In 2024, however, Labour managed to win 37 of the 38 red wall seats. Another electorally pivotal group of cross-pressured voters are fiscally conservative, socially liberal voters in the South. These voters traditionally supported the Conservatives but have become increasingly alienated by the party’s right-wing stance on cultural issues.

What proportion of the electorate is cross-pressured? Using responses to the BES Panel’s widely used authoritarian-libertarian index and left-right economic index, the electorate can be divided into four categories based on their economic and social values: “right-authoritarians,” “left-libertarians,” “right-libertarians,” and “left-authoritarians”.

Left-authoritarians have more progressive economic attitudes and culturally conservative views, while right-libertarians have conservative economic views and are progressive on cultural issues. Right-authoritarians are conservative on both economic and cultural issues, while left-libertarians have progressive economic and cultural preferences.

The proportion of the electorate in each category at recent key moments in British politics is shown in Table 1. Over the last three decades, approximately half of the electorate can be classified as cross-pressured, with a roughly equal split between right-libertarians and left-authoritarians. For comparison, in nine other Western European countries, based on 2017 data, just under 30 per cent of the electorate is classified as cross-pressured (albeit using different questions). Although the share of cross-pressured voters is higher in the UK than in many European countries, it has remained stable, whereas it has increased in other European countries from a level of less than one in five voters in the 1990s.

.png)

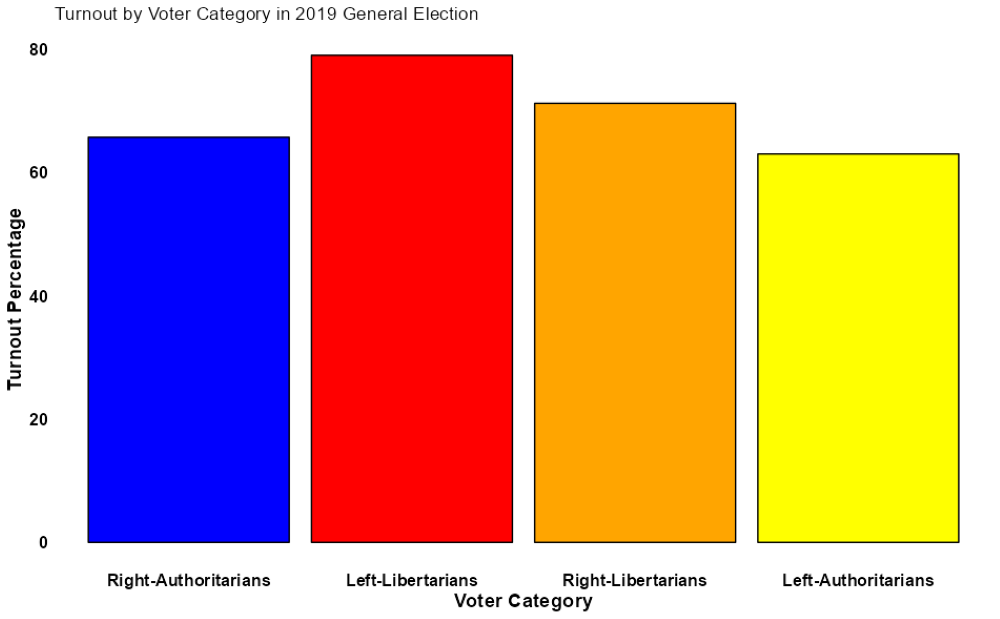

Cross-pressured voters have been thought to be less likely to vote as they are confronted with a situation in which no party represents their views on all dimensions. To examine turnout rates among different voter groups, the data from the 2019 general election is used rather than the 2024 election, as there is currently a validated turnout measure for the former but not the latter. The turnout rates among different groups are displayed in Figure 1.

The evidence that cross-pressured voters are less likely to vote than other groups is mixed. At 62 per cent, the turnout rate among “left-authoritarians” was the lowest among the four voter categories, but it was almost identical to the level for right-authoritarians (63 per cent). Among the other cross-pressured voters – right-libertarians – the turnout rate (71 per cent) was substantially higher than the overall average but still considerably lower than left-libertarians (78 per cent). An interesting development to watch is whether turnout in 2024 among left-authoritarians was higher, given the popularity of Reform, which some culturally conservative voters think of as being to the left of Tories on economic issues.

If cross-pressured voters are responsible for the increased electoral volatility, they should be more likely to switch parties from one election to the next than “ideologically consistent” voters. In Figure 2, the proportion of each voter group that voted for different parties in successive elections is shown. For 2024, the stated vote intention from the February-May 2024 wave of the BES panel was used.

.png)

Vote switching is, broadly speaking, higher among the cross-pressured voters. In the four elections between 2015-2024, the average level of defections among non-cross-pressured voters was thirty-three percent. By contrast, the corresponding figure among the two cross-pressured groups was thirty-nine percent. It should be noted, however, that the greater volatility among the latter group is driven by the especially high level of vote-switching among left-authoritarians.

Of course, the 2024 election stands out for the high defection rates amongst all voters. Focusing on the cross-pressured voters, among the left-authoritarians who indicated they would vote for a different party in 2024 than they did in 2019, if the “Don’t Knows” are excluded, almost 30 per cent indicated they would switch to Labour, while 40 per cent of switchers said they would move to Reform. Turning to the right-libertarians who indicated they would switch parties in 2024, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, 14 per cent said they would defect to Reform, while only seven per cent said they would switch to the Liberal Democrats. One possible explanation for this is that economic issues were highly salient in the election many of these voters felt the Liberal Democrats were too left-wing on socio-issues.

The high degree of volatility that has come to characterize British elections has many sources. Parties must contend with voters prioritizing different sets of issues and the presence of a substantial share of the electorate with combinations of preferences on economic and cultural issues that do not line up on the left-right ideological axis in a way that mirrors the divisions between the parties. One of the most consequential and difficult strategic challenges facing British political parties will be how to assemble and keep together a coalition that includes their “ideologically consistent” supporters and voters who feel ideologically close to them on one dimension but feel other parties better represent their values on other issues.

Zain Mohyuddin is a researcher at UK in a Changing Europe.