Baroness Gisela Stuart reviews Angela Merkel's 'Freedom: Memoirs 1954 – 2021'

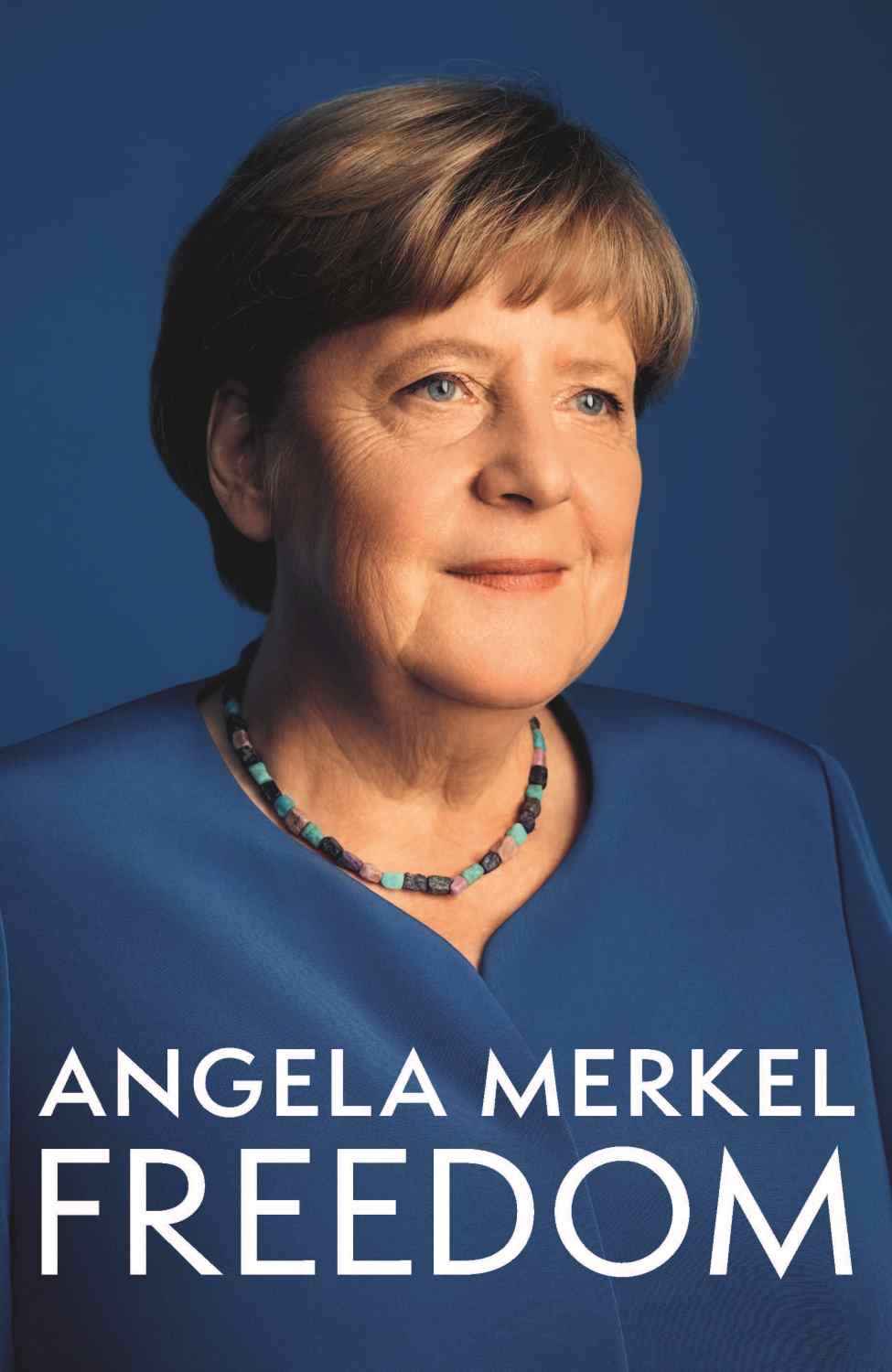

Angela Merkel, 2015 | Image by: 360b / Alamy Stock Photo

5 min read

Composed in her trademark calm delivery, but infused with little to capture the reader’s curiosity, Angela Merkel’s achievements – as well as her failures – deserve more insightful analysis than this

“This book tells a story that will not happen again, because the state I lived in for 35 years ceased to exist in 1990”: these are the opening lines of Angela Merkel’s memoirs.

Now 70 years old, she spent the first half of her life in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), under a political system she rather benignly describes as socialism without freedom. After German unification she joined the Christian Democrats (CDU) and from 2005 to 2021 served as the chancellor of the economically powerful Germany. She was a stable and important voice in the European Union and on the world stage.

Merkel reflects on her life before 1989 and after unification in 1990. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, nothing was going to be the same again – for her and for the 16.4 million people living in the GDR. Merkel also has her own political turning point after which nothing would be the same again for her, her party and much of Europe.

It was the night of 4 September 2015 when she decided not to turn away the refugees who were arriving on the Austrian-German border from Hungary. She is clearly irritated that her slogan “Wir schaffen das” (“We can do this”) is quoted back at her in isolation but doesn’t provide us with a wider context herself.

In 2013 the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) “was founded in reaction to my policy decision regarding the euro rescue package but had fallen short of the five per cent threshold in the elections”. Merkel accepts that the refugee crisis gave the AfD a fresh impetus but is confident that the democratic parties have considerable influence over how strong the AfD can become in practice.

Hamburg, February 2016: Prime minister David Cameron and chancellor Angela Merkel attend a dinner| Image by: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Hamburg, February 2016: Prime minister David Cameron and chancellor Angela Merkel attend a dinner| Image by: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

She rejects the idea that it is the role of the large political parties to absorb the extremes, either from the left or the right, if doing so runs contrary to her own principles. What matters for Merkel is the unity of the European Union, the values of Nato and “the preservation of human dignity, especially for people in distress”. The forthcoming German elections will show if the AfD has been contained.

There are few occasions, usually when she feels patronised by men or underestimated by politicians from the West, where Merkel actually shows frustration or anger.

She cannot understand being criticised for voting against same-sex marriage. Had she not paved the way for a free vote to take place? Assuming the vote would be carried, she followed her conscience, subscribing to the traditional view that, under the German constitution, marriage was only possible between a man and a woman. Too often she resorts to universal human values or existing legal frameworks to defend specific decisions without acknowledging her role as a political leader and legislator.

While she is fascinated by the late Queen Elizabeth’s conversational technique, British prime ministers get peripheral mentions only

This isn’t an easy book for a British reader. The quality of the translation is uneven and whole sections are merely descriptive, failing to offer insights or analysis to capture the reader’s curiosity.

But it’s the relative absence of references to the UK and British prime ministers which gives cause to reflect. If in doubt, Angela Merkel turns to the French president, the American president, the secretary general of Nato, the EU and the president/prime minister of whichever European country that requires assistance. While she is fascinated by the late Queen Elizabeth’s conversational technique, British prime ministers get peripheral mentions only.

There is no ambiguity in her views on Brexit. “To me, the result felt like a humiliation, a disgrace for us, the other members of the European Union – the United Kingdom was leaving us in the lurch.” Blaming David Cameron for setting himself on a path to an inevitable referendum, Merkel concludes that there wasn’t more she could have done to help him.

Big themes like Vladimir Putin and Ukraine, dependency on Russian energy, civil nuclear energy, German defence engagement and Israel are covered but from a narrow focus in that quiet, unexcited style that was so much part of Merkel’s political success.

Big themes like Vladimir Putin and Ukraine, dependency on Russian energy, civil nuclear energy, German defence engagement and Israel are covered but from a narrow focus in that quiet, unexcited style that was so much part of Merkel’s political success.

The chapter covering the period from November 1989 and to December 1990 is an exception. Starting with mixed feelings, she becomes politically active, campaigns with the liberal East German group Democratic Awakening and in 1990 wins a direct mandate as candidate for the Christian Democrats. Why the CDU? She offers some hints but, yet again, with every answer she raises even more questions.

Maybe this is the only book she could have written – but her time in office, her achievements as well as failures, deserve a more insightful analysis than this.

Baroness Gisela Stuart is a Crossbench peer

Freedom: Memoirs 1954 – 2021

By: Angela Merkel

Publisher: Macmillan