Charles III's first King's speech – and a history of debuts

7 min read

As the King performs what is perhaps his most important duty as head of state for the first time, Daniel Brittain reminds us that not every debut has been a nerveless success

The coronation in May was spectacular and both palaces will be determined that the King’s first state opening as monarch is no less of a dazzling success.

Last year the King deputised for Her late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II at the very last minute, but this November he’ll be wearing the imperial state crown and his state robe. He’ll refer to “my government” not “Her Majesty’s government”.

Every year’s ceremony is the product of intense planning and there is even more for the sovereign’s first. That is not to say they have all gone perfectly, however. In the 20th century, one led to an inquiry and another was just plain embarrassing.

A history of other debuts shows what can go wrong, from downpours to stampedes and fumbling chamberlains.

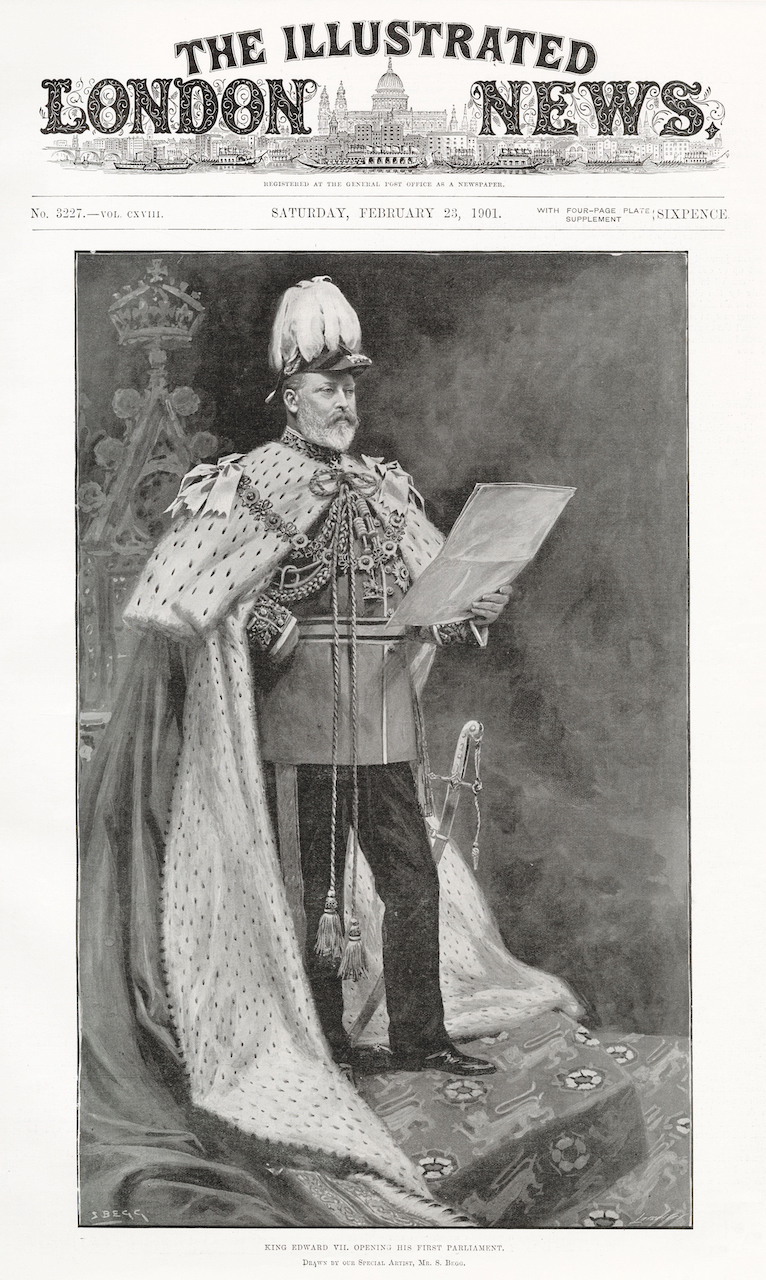

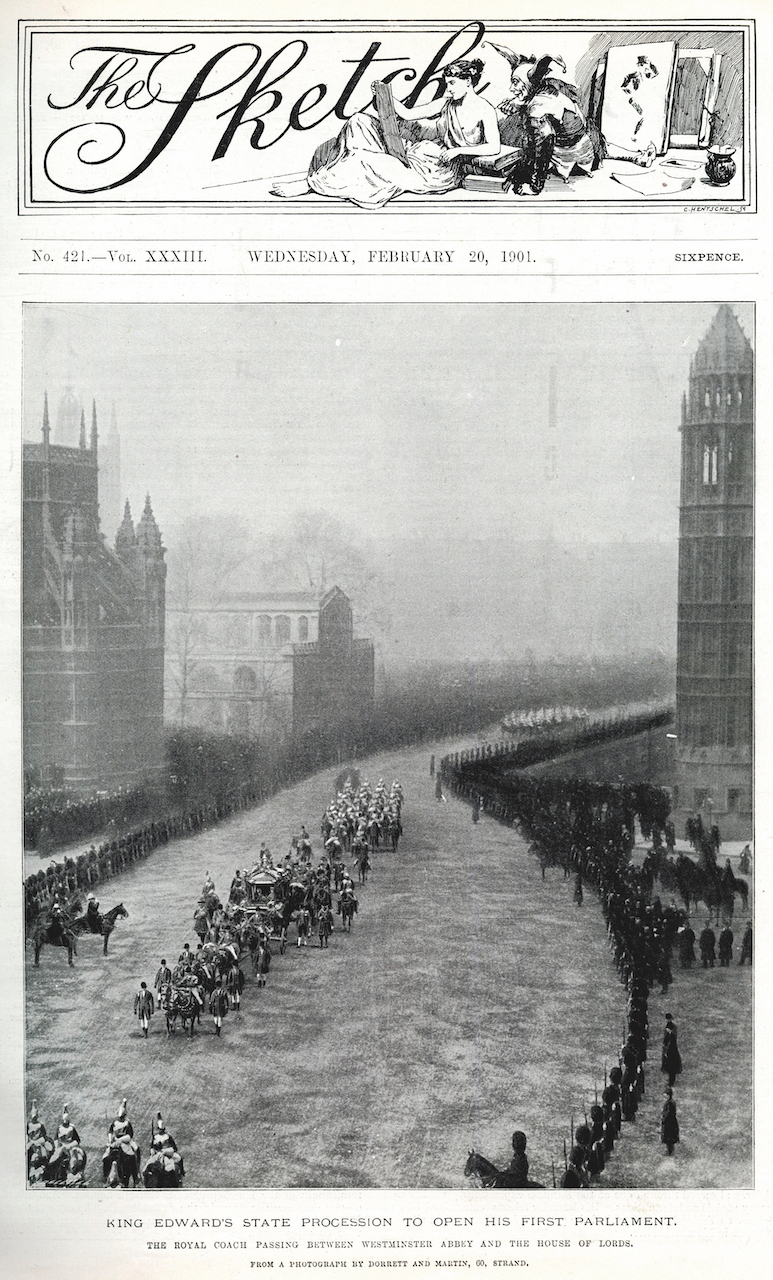

Edward VII: 14th February 1901

Edward VII, that most outwardly confident and exuberant of kings, was said to be frightened by the state opening, yet with his love of pomp and circumstance he established the ceremony as we know it today. However, the most remarkable fact about his first state opening was that he was actually there.

Edward VII, that most outwardly confident and exuberant of kings, was said to be frightened by the state opening, yet with his love of pomp and circumstance he established the ceremony as we know it today. However, the most remarkable fact about his first state opening was that he was actually there.

His mother hadn’t attended for 15 years and hadn’t delivered the speech in 42 years. The excitement this generated resulted in a stampede by MPs, injuring some, as they ran for places in the Lords. The two Houses instituted an investigation.

George V: 6th February 1911

All new sovereigns must make the accession declaration and sign the oath at either their first state opening or their coronation, whichever comes first. For George V, it was the state opening. He made it known that he’d refuse to open Parliament if the existing oath was used, containing as it did anti-Catholic phrases such as “the sacrifice of the mass, as they are now used in the church of Rome, are superstitious and idolatrous”. The Liberal prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, agreed and new words were set out in the Accession Declaration Act. The monarch would simply declare: “I am a faithful Protestant”.

When it came to the day, George wrote in his diary: “It was a terrible ordeal as the place was crowded in every part and I felt horribly shy.” He also confided: “My voice was somewhat nervous, but was fairly well heard… It was a great relief when we got back to the robing room.”

Relief, too, for the lord great chamberlain, the King’s representative at Parliament, who was also pleased he’d managed to acquire a new uniform. It was traditionally blue, but Lord Carrington fancied the earl marshal’s scarlet, so he’d written to the palace to request the change. Conveniently, the recipient was his brother William, keeper of the privy purse, and it was agreed. The present lord great chamberlain will be wearing his great-great-uncle’s uniform on 7 November.

The imperial state crown – which weighs 1.6kg – was carried in front of George V, still uncrowned at the time. Nothing unusual in that. Edward VII never wore it at the ceremony. It was a radical change when George V wore it in 1913 and the tradition has endured.

Edward VIII: 3rd November 1936

When he arrived for his only state opening, Edward VIII was just five weeks from abdication, and the peers and MPs gathered in the Lords would have heard rumours about Mrs Simpson all summer. The King’s private secretary Alec Hardinge had known rather longer.

Despite the crisis fast approaching, the royal archives contain detailed correspondence about the state opening, with the King very much involved. There was a lot of juggling as to which peers would carry the crown, cap of maintenance and sword of state.

Then there was the oath. Hardinge wrote that he’d “explained to the King that he had to make the anti-popery declaration”. Edward thought it inappropriate for an institution supposed to shelter all creeds, but didn’t make an issue of it. He was, however, determined to put on a good show, aware that he’d be compared to his father “who was always superb on these occasions”.

There was also debate about which carriage should be used, with Hardinge writing tartly: “there will be no question that His Majesty should drive in anything except the gold coach”. On the day, drenching rain meant the gold coach stayed in the royal mews and a Daimler was pressed into service. The oath was duly made and the Bible kissed. The spiky diarist Henry ‘Chips’ Channon MP noted that Edward “appeared like the Boy Prince of 1911 at the investiture in Caernarfon. He was not nervous, not fidgety and was severely dignified and watched his long train being put in place with amusement.”

Afterwards the King asked the cabinet to sign his copy of the speech, which they duly did.

Lord Cholmondeley (lord great chamberlain for the reign) also made a request, writing to the King: “in accordance with immemorial custom [the LGC] begs to be allowed to retain the two chairs of state… which are no longer required”. No reply was forthcoming, but the family did end up with the consort’s throne.

George VI: 26th October 1937

Britain’s reputation for perfect ceremony came a cropper at George VI’s first state opening. He’d taken the unusual precaution of asking for a rehearsal the week before to get the feel of the place. The speech itself was written to avoid any tricky words for his residual stutter.

Come the day, the ceremony went bizarrely wrong. All the processions had been given exact times, and the MPs duly arrived to crowd into the space between the doors and the bar of the Lords Chamber only to see … well, no one. As Hardinge sarcastically wrote: “it doesn’t look very well if they [MPs] have to make their bows to an empty throne”.

So what went wrong? The lord great chamberlain had been due to dispatch the King and Queen from the robing room at precisely two minutes to 12 for their arrival in the Lords at noon, just before the Commons arrived. It seems the Earl of Ancaster didn’t get them out of the robing room until Big Ben was striking 12. Lord Ancaster had form on dithering. After the coronation five months earlier, the King had written: “his hands fumbled and shook so I had to fix the belt of the sword myself”. The King was determined his second state opening would go smoothly and, shortly beforehand, summoned Lord Ancaster to the palace for a little chat.

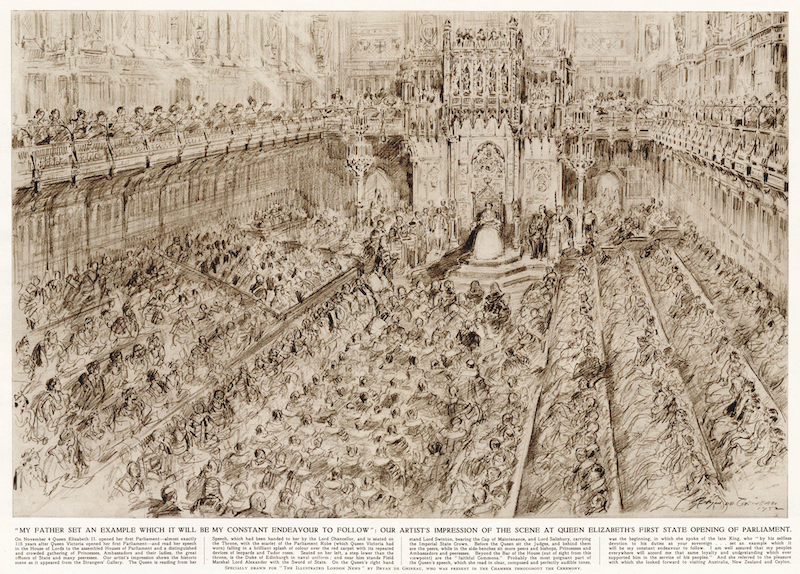

Elizabeth II: 4th November 1952

The first photos of the procession were taken, and Prince Philip sat on a chair next to Queen Elizabeth II (like Camilla last year), only later graduating to the consort’s throne. (Camilla is to be given the consort’s throne from the start.)

As Lord Janvrin, one of Elizabeth’s former private secretaries, tells The House, she regarded state opening as hugely significant in her role and would talk to the prime minister about it in the weeks leading up to the day. Almost from the outset the Queen’s Speeches were notably more impersonal in tone than her predecessors’. She would not have said, as her father George VI did: “I rejoice to know that the outlook for trade and industry remains favourable.”

Charles III: 7th November 2023

From what we already know, Charles III is very much an activist monarch. If the King uses a few personal phrases in his speech, that would mark a change from his mother’s style. As a spectacle it will be the first time since 1950 that a King and Queen will attend in their robes and trains. This has thrown up debate among the organisers as to whether they should enter the Lords Chamber separately, using the two arched doorways, or follow precedent and both go through one. I understand the decision rests with the King and Queen; my money is on a dramatic visual change.

Finally, something for the eagle-eyed: Lord Carrington, this reign’s lord great chamberlain, has blinged up with a new ceremonial key to the palace on his uniform, complete with CIII initials. Didn’t come cheap, I’ve heard. Not much change from £5,000.

The writer is most grateful for the permission of His Majesty King Charles III for the use of material from the royal archives. George V diary RAGV/PRIV/GVD/1911:6 February. Alec Hardinge correspondence RAPS/GVI MAIN/1005. Sincere thanks to the parliamentary archives and Julie Crocker of the royal archives.