'Fascinating': Lord Wallace reviews 'Black Redcoats'

Image by: J.T. Lewis / Alamy Stock Photo

4 min read

Matthew Taylor has produced an engrossing study of how thousands of enslaved African-Americans fled to fight with British forces during the 1812 Anglo-American war

Many peers have enjoyed conversations on British history with Matthew Taylor in the Government Whips’ Office. Now he has published his first book, which throws a distinctive perspective on the War of 1812.

Using a wide range of archives and local histories, he has produced a fascinating retelling of the conflict, exploring “the ironies and hypocrisies” that surrounded the recruitment of Black marines, and tracing their descendants in the Merikin community in Trinidad and the Afro-Seminoles of Florida and the Bahamas.

Britain and the United States had drifted into war both from clashes over the continental blockade against the French – and from American hopes to take advantage of British distraction to conquer Canada. With British soldiers heavily committed in Europe, naval forces gathered in Chesapeake Bay, facing the slave states of Virginia and Maryland. Soon after their arrival, slaves began to escape to British ships.

In the earlier War of Independence, the British governor of Virginia had issued a proclamation promising freedom to slaves of American revolutionaries who fled their masters to join British forces. Several thousand did so. Memories of this – combined with stories of Lord Mansfield’s ‘Somerset’ judgement in 1772, which ruled that “the air of England is too fine for a slave to breathe” – triggered an initial flow of escapees from the spring of 1813, providing expert guides for British raids on the mainland. Admiral Cochrane, who had employed former slaves as marines in the West Indies, then adopted slave emigration as a strategy.

Black troops were among the small British force that in 1814 burned Washington

A second proclamation offered freedom and resettlement as a reward for military service, with the first of six companies of colonial marines established on an island offshore. Fears of a slave rising undermined Virginian morale; Black troops were among the small British force that in 1814 burned Washington and bombarded Baltimore. The American lawyer and author Francis Scott Key was, Taylor tells us, on board a British warship during that bombardment, attempting to negotiate the return of his escaped slaves. Key’s relief at seeing “the Stars and Stripes still wave over the land of the free”, as he afterwards wrote, did not extend to freedom for his own property. (It was into his eponymous bridge in Baltimore a ship tragically crashed recently.)

The southern campaign that followed recruited many more escapees from Georgia, while a separate initiative in Western Florida trained and armed many more. But General Andrew Jackson, commanding experienced US troops (including the young Davy Crockett) who had been fighting the native Creeks, blocked the intended capture of New Orleans, and belated news of a peace treaty ended the conflict.

Taylor has carefully tracked down where these Black soldiers came from, and where they settled after the war ended. The treaty allowed for compensation for loss of property, and American slave-owners provided details on who had escaped and where they feared they had gone to. Astonishingly, the tsar of Russia, Alexander I, acted as arbitrator in assessing their claims against the British.

Taylor has carefully tracked down where these Black soldiers came from, and where they settled after the war ended. The treaty allowed for compensation for loss of property, and American slave-owners provided details on who had escaped and where they feared they had gone to. Astonishingly, the tsar of Russia, Alexander I, acted as arbitrator in assessing their claims against the British.

Taylor notes the deep ambiguities of the British approach. Cochrane was himself a slave-owner in the Caribbean, though some of his officers were convinced abolitionists. They honoured their promises to the marines and their families. Some were shipped to Nova Scotia; others to Trinidad, which still has a distinct community descended from their settlement. Many of those recruited in Florida stayed on, setting up villages in what had been Spanish territory, allying with Native Americans against US settlers pushing south. With British weapons and uniforms, they held the marine fort until 1816, after which their remnants escaped to the Bahamas. The “historic site” still flies the Union Jack.

Lord Wallace of Saltaire is a Liberal Democrat peer

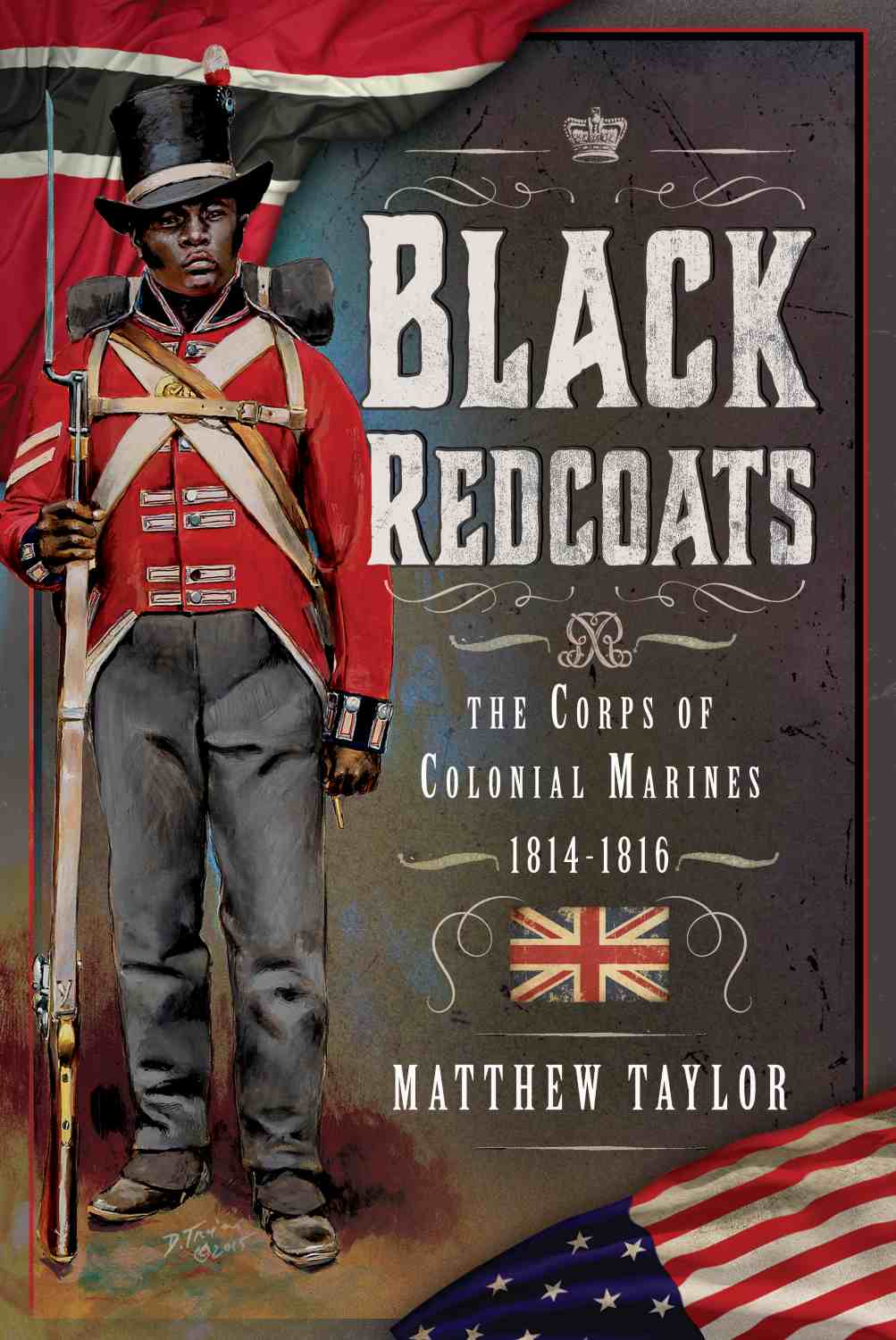

Black Redcoats: The Corps of Colonial Marines 1814-1816

By: Matthew Taylor

Publisher: Pen & Sword Military